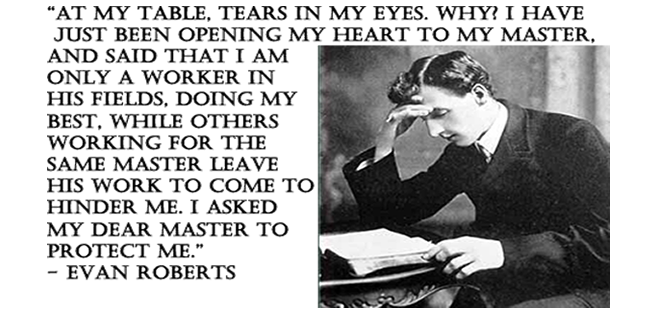

EVAN ROBERTS

The Great Welsh Revivalist And His Work

by D. M. Phillips

About This Book

This is an extensive biography written about Evan Roberts.

There is nothing quite like this comprehensive 542-page appraisal of Evan Roberts life and ministry, written by a keen supporter and admirer of the Revivalist. Daniel M. Phillips, a minister himself and often a companion of Evan Roberts on many of his journeys, produced this elaborate and often grandiose view of the young missioner, with such zeal that many will consider it an embellished overstatement. However, it has always been the standard work on Evan Roberts and it is essential reading for serious students today.

Mr. Evan Roberts has no part whatever in the bringing out of this Volume. He has permitted me to publish his First Sermon, his Sayings, his Letters, and his Poetry, and that is all. The Author, also, will not derive any financial benefits from its publication. Should the volume return any profit, it will all be given to the Foreign Mission, or some other deserving religious cause.

Introduction.

Evan Roberts is a phenomenon. On this there is but little diversity of opinion. Only a man with something extraordinary belonging to him could have attracted the attention of the religious world as he has done.

People have travelled from Australia, Africa, Asia, America, and various parts of Europe to see him and the Movement of which he is the central figure. Yet, owing to his humility and positive unwillingness to be thought of as possessing any superiority, he has unconditionally refused to see most of these visitors, notwithstanding the high position of many of them as religious leaders. Even the antagonists of the Christian religion admit that he is a strange and inexplicable person, and very few of them dare to doubt his sincerity. His life in its various aspects before the public during the last eighteen months has proved his motives to be pure and holy, and that he is not governed by any principle, but a burning desire to save souls and glorify Christ. His great influence and success cannot be attributed to anything but his goodness and the fact that the Holy Spirit is upon him.

As to his goodness, there is a consensus of opinion among those who have had the privilege of knowing him, His comrades at Loughor, his fellow-workmen, and his masters testify that there was never anything doubtful in his character; the churches of Moriah and Pisgah where he brought up bear witness to his unblemished morality, his liberality and faithfulness; other denominations looked at him as an exemplary young man, and irreligious people respected him greatly. This testimony is confirmed by the students with whom he came in contact at Newcastle-

Emlyn, and three of them who have replied to the writer in answer to enquiries say that he is the holiest person they have ever met; and one of them affirms that Evan Roberts has been the means of changing his life entirely. Although he will not give any facts concerning his life and work to correspondents who have come scores and some of them hundreds of miles with the intention of having materials for articles on him, yet they honour him. Yea, they honour him all the more, because they can see that he does not court their influence and their help. True, they are disappointed, because of his reservedness; never-the-less they admire the purity of the man. I have seen as many as ten correspondents of the leading papers of England, Scotland, and Wales endeavour to see him after some of the meetings, and he declining absolutely to be interviewed.

He must have a certain proof that a correspondent will adhere strictly to facts without magnifying them before he will entertain the idea of supplying him with anything concerning his Life or the Revival. In less than six weeks after he left Loughor, letters reached him from different countries, from important publishing firms, asking for biographical facts, but he definitely declined to answer in every case. Since the Movement commenced, nothing has grieved him more than an occasional exaggeration in the papers of his importance as a force in it. In his opinion, that takes the glory that should be given to God. But be it understood that the said importance given to him by correspondents was due to the idea they had formed of his sincerity and goodness. In a few days after he left Loughor a correspondent of high standing said of him:

"Wherein lies the charm of the man and his power? Perhaps the best answer is that he has an indefinable something in his manner and style.

His joyous smile is that of a man in whom there is no guile. His genuineness is transparent, and he convinces people that his belief in what he preaches is impregnable. Another wrote - Evan Roberts is real.

This realness is most likely the chief source of his power. He is probably far more real than he himself knows, or than any of his critics and wouldbe teachers and admonishers believe. No one man in a million, perhaps, dare be as honest to himself and to others as Evan Roberts is without daring and without effort and without design. He knows without learning what other people have to spend years in acquiring and are then imperfect. He sees and feels what they do not believe even exists, and so he does his work, and will do it as long as his strength holds out and he retains his spiritual vision unimpaired. After careful observation and investigation since the paper took up the Revival, I have found that the above quotations represent the opinion of all the correspondents who have had the privilege of personal knowledge of Evan Roberts. It is simply surprising to think of the place newspapers and magazines have given to him. There is hardly any daily paper or a periodical in England and Wales that has not published long articles on him and the Revival.

Even the rationalistic as well as the secular and religious press has taken special notice of him, and in some instances has highly estimated him.

This is sufficient evidence that there is some moral and spiritual atmosphere surrounding the man which makes itself felt, and convinces people of his good motives.

Again, the consensus of opinion as to his motives is not less general when we come to some of the most religious men who have made his acquaintance.

The Rev. F. B. Meyer, B. A., London, says of the Revivalist in a letter to the writer - "I have the privilege of personal friendship with Evan Roberts, and greatly thank God that he will not go in front of the Divine Spirit, but is willing to stand aside and remain in the back-ground, unless he is perfectly sure that the Spirit of God is moving him. It is a profound lesson for us all."

Mr, Arthur Goodrich, B.A., London, makes these remarks in an article on Evan Roberts and the Welsh Revival in the Homiletic Review for March, 1905: - He does not consider himself an inspired prophet or a magnetic preacher. He spoke to me one day with evident anxiety of a newspaper report which spoke of his personal magnetism. There's nothing in it, he said, in substance. "It's not my magnetism, it's the magnetism of the Holy Spirit drawing all men to Him." He considers, I believe, that God has given him work to do - great work; and he is confident that He will help him to do it. Whether his share in the work is great or little I think Evan Roberts cares as little as any human person can care, as long as the work is done. No one of all those who have watched him more closely and continuously than I have, has seen a single sign of any tendency in him to place himself ahead of his co-workers. Personally, I think I have never met a man who appealed to me as being so completely consecrated to his cause as this young man of twenty-six years trained in the colliery and at the smithy. When one thinks of it, no young man of his years and native environment could have endured against a tide of personal success unless he had an enduring grip upon mighty moorings. These quotations only echo the opinion of hundreds of others who have had fellowship with him. Shortly after the Revival broke out, the leading ministers of the various denominations in Wales and the Welsh Bishops showed their deep sympathy with him and his work, and many of them did their utmost to further and direct the current of the mighty religious wave.

They did this because they thoroughly believed in his sincerity and the Divine origin of his message.

True, a few disagreed with him, and in the severe test he has been put to, his invariable replies to his critics have been: - "Let then alone"; "Pray for them"; "Fear not"; "My feet are on the Rock".

Often it has been said that Evan Roberts is not the author of the Welsh Revival. Well we know that, and we thank God for it. Had Evan Roberts been its author, we would rather be without it. The efficient cause of the Revival is to be found amid the everlasting hills in the heart of God. The movement bears the marks of its origin, and the most spiritually-minded people are agreed that these marks are Divine beyond dispute. Without the intervention of the Divine a true revival is impossible as we shall see presently, there are sufficient evidences that the Holy Spirit is the dynamic force in the Movement. But it must be borne in mind that the Movement has its human side. It can be said that it has a human cause or condition as well as Divine. That is subject to psychological and moral laws. There could be no greater error than to think that the Revival is outside the domain of these laws. God does not give an outpouring of his Spirit except in accordance with the great general principles of human nature. A Revival otherwise brought about would be unnatural. To find the condition of this moral and spiritual upheaval we must take in all the Christian work done in Wales since the Revival of 1859. A revival is similar to letting out the contents of a reservoir. When all the contents have run out it must have time to fill before another outpouring is possible. Now since 1859 what the Church in Wales has been doing is filling a moral and spiritual reservoir in the heart of the nation through different means. In the mental, moral and spiritual world there is a law of conservation of energy similar to that of the natural world. This conserves all the labour of the church. It secures that no chapter read, no prayer offered, no hymn sung, no sermon preached, no temperance lecture delivered, is lost. All are treasured in the minds of the hearers.

The different religious sects in Wales have had their general assemblies, unions, and conferences annually, quarterly meetings and associations, anniversaries once or twice a year, in most of the churches in populous districts, and preaching twice every Sunday during the year. These saturated the mind of the nation with religious ideas. Again, all the denominations have their annual singing festivals, and in virtue of these the young people commit the hymns to memory without any effort.

Great endeavours have been made to further the temperance cause by men and women's unions. Add to these the excellent Sunday School organization in Wales with its system of Bible classes. Annual Sunday School examinations are arranged by the different religious bodies, and people of all ages sit for them, and they are trained all the winter to that end. Many between fifty and seventy pass these yearly, as well as young people and children. To give one instance, the Presbytery or Monthly Meeting of the Calvinistic Methodists of East Glamorgan passed over two thousand candidates in 1906. Then there is the great reading of English religious books in the Principality especially during the last twenty-five years. Let me note another great factor, namely, the innumerable prayers to God from hearts longing for a religious awakening. Between these different branches of religious work, the moral and spiritual reservoir mentioned had filled, and it only required the right man under the guidance of the Holy Spirit to turn the tap to let its contents run forth.

And it pleased God to pass the learned and the great in human estimation, and call a consecrated, timid young man from the Grammar School to perform that function. Fair it is to say, that the greatest scholars of the nation said in the face of this, Glory be to God in the Highest. For at least two years people of strong religious intuitions had noticed that the reservoir was overflowing here and there, and they hoped for great things. As will appear in a future chapter, a marked awakening had taken place in South Cardiganshire. Many other places had experienced similar things but on a narrower scale. Everything was ready, only to have the breathing of the Holy Spirit. The seed was in the ground, and it only required the Spring rays of the Sun of Righteousness to bring it forth with power and splendour.

It seems to me that a powerful revival is impossible without long preparation on lines similar to the above. There must be a deposit of material for it. Take the revival in Egypt when the Hebrews fully realized that they were a nation, and you will find it was due to a long preparation, and so of the national revival in the time of King David.

After reading the history of revivals in Europe and America, we find that the same is true. The revival that gave existence to the Calvinistic Methodist Denomination in Wales was due to a great awakening brought about by schools planted all over the principality by the Rev. Griffith Jones, a clergyman of the Church of England, to teach Bible reading. The same principle holds good in the case of other revivals in Wales. A grand illustration of this principle is supplied by the Revival which broke out on Khassia Hills in February, 1905, as a result of reading the account of the Welsh Revival. The missionaries had laboured hard for over sixty years to sow the Gospel seed there. This seed had in it spiritual vitality, and the Holy Spirit used the accounts alluded to as means to quicken the people and that has resulted in over five thousand conversions on the mission field in Khassia.

We observe that this is God's general method. Take the Spring for instance. Is it not due to a course of preparation? Certainly it is. The earth has been prepared by the great forces and processes of nature in Autumn and Winter, and man has been at it busily doing his part in ploughing and tilling the land, sowing the seed, and weeding the tares.

When all is ready the Almighty breathes his life into every grain, every blade of grass, and every flower, and they burst forth with wonderful originality and spontaneity. In this way the work of preparation on the part of God and man is crowned. Had the human race not to undergo a long process of preparation to receive the Incarnation, which brought about an epoch-making revival in the history of the world? Were not the disciples trained by the great Master to be instruments in the hand of the Spirit to bring about such a moral revolution on the day of Pentecost?

The people were prepared by the preaching of John the Baptist and Christ in the same way; and that preparation had much to do with the day of Pentecost. Were this principle not the true explanation of the human condition of revivals, there would be no encouragement for all the endeavours of the Church throughout the ages.

Is there not a certain amount of extravagance and emotionalism displayed in Evan Roberts's Revival? True there is. Had it not been so, it would not be a revival. When the vilest characters see their sin in its real nature, they cannot be cool. Their conscience gets too intense. Church members cannot be emotionless, when their worthless past life is ploughed, and their deceit and hypocrisy are revealed to them. When the pangs of true repentance writhe the soul, it is a relief to shout. Without deep emotion no great thing can take place in the soul. Emotion under proper control is the grandest thing in existence, and the great power that moves the world in its upward march. All epoch-making men are men of strong emotion. Yea, more, it was the emotion of God's heart that moved Him to perform the greatest act of self-sacrifice, which has and will issue in the salvation of a great multitude. To condemn emotion is to condemn one of the most glorious powers that the Creator has implanted in our nature. But well we know that it is dangerous power unless kept under control. In this Revival a few lost control over it; but that was only repeating the history of all previous religious revivals. Copious examples of this are to be found in the history of the Reformation, the American, and other revivals; and according to the nature of things it could not be otherwise. The nature of the materials God has to work upon in a revival is such that it cannot be different. Hence it will be the same in the history of all future awakenings. Nevertheless, that does not make a revival less valuable. There is an enormous amount of weed produced by the most glorious Spring, but what is that compared with the corn, fruits, and other products? In a great outburst of life like the Spring the venomous germs are developed of necessity the same as the precious seed. So in a spiritual Spring like a revival, the spiritual warmth is an occasion to draw out evil possibilities to an undue measure. No person of sober mind would be offended with the Spring, because of the weed it produces; no man of true wisdom will think less of the revival because of the moral weed that it grows. A broad-minded man will overlook these small imperfections, and see that the nature of the case necessitates them. We are far from justifying the extravagant cases of emotion produced by the Revival, but history, experience, and the Bible show clearly that they accompany all true revivals, owing to what man is, and not because anything in God calls for them. Physical concomitants of the Revival are not to be taken as a sure sign of the working of the Holy Spirit, nor on the other hand that the persons in whom these concomitants appear are not undergoing the process of true conversion. We must wait for results to know that.

Many of the converts will backslide. There is no doubt about this. But does that prove the Revival to be less divine? It does not. Did not many hypocrites enter the church in the Apostolic Revival? And did not Judas Iscariot who adhered to Christ for years betray Him? Yet that did not make the conversion of the other disciples less valuable and real. Does not the Great Teacher indicate plainly in the Parable of the Sower that only twenty-five per cent of the seed will fall into good ground and bear fruit. And I say that if only twenty-five percent of the converts of this religious upheaval were truly converted, it will be a glorious movement.

The results of it have been great and far-reaching. It has done great things to one class of Church members. Religious work had never been more strenuous in Wales among the most faithful members than before the Revival broke out; but there was another class doing nothing.

Hundreds of these have been aroused, and are now indefatigable workers. Talents were discovered in the church that no one thought of, and these talents are full of activity at present. The salvation of others has come to be of great importance, and people have realised that they are their brother's keepers; the services are better attended than ever; family worship has been instituted in thousands of homes; the demand for Bibles has been such that booksellers in some cases found it difficult to supply it; some of the finest hymns have been composed in the heat of the Revival; total abstinence is believed in more than ever, hundreds of people have paid debts, which they were not compelled to owing to the Statute of Limitations; many who had stolen things fifteen and twenty years ago have sent the full value with interest to the persons from whom they stole them; hundreds of old family and church feuds have been healed; triumphant joy has filled many churches; the different religious sects have come nearer to each other, and small differences have been minimised, and thousands of those who have joined the churches are energetic workers, and do much to influence others. Among these are some agnostics, infidels, prize fighters, gamblers, drunkards, as well as theatricals, and they are as enthusiastic if not more in their new sphere as they were before their conversion. Hundreds of homes have been entirely changed, and where there were poverty and misery before, there is plenty of all the necessities of life now, and happiness. A movement that can produce these results cannot but be divine in its nature. It has changed the whole moral and spiritual aspects of many districts, and its future effects must be great. To quote again from the above letter of the Rev. F. B. Meyer, B.A., regarding the results of the Movement, he says: -

"Judging by the fruits, in the vast multitude who have been truly converted and have joined the churches, and the transformation wrought over wide districts of the country, it is impossible to doubt that there has been a real and deep work by the Spirit of God, similar to that which accompanied the labours of the Wesleys and their contemporaries. For this one cannot be too thankful. Mrs. Baxter, who twice visited Wales to estimate the Movement, remarks in the 'Eleventh Hour' for January, 1905:

- The Revival in Wales has undoubted marks of Divine power and working. This Revival will not result in the formation of a new denomination like the one that produced the Calvinistic Methodists of Wales, and we do not want that; neither will it produce as rich a hymnology as that perhaps; it may not give us so much theology as the revival of John Elias, Williams of Wern, and Christmas Evans, nor be such an impetus to the formation of a system of education as that of 1859; but we believe it will do more than any of them in creating high moral and spiritual ideals and aspirations, and that is what the nation stands in need of now, and not so much the things produced by the former revivals.

May this revival spirit spread and kindle many nations, and bring multitudes to the Saviour.

More space could not be given to the third and fourth journeys as the size of the book had swollen so much, owing to the addresses, articles, and letters. The writer hopes to deal with these fully in a future volume.

It is my duty to acknowledge the kindness of the Editors of the South Wales Daily News and the Western Mail for giving permission to use the valuable articles that appeared in their papers on the Revival, as well as the Editors of other papers, articles from which are reprinted in the volume; also persons who have kindly sent me their impressions of Evan Roberts and the Movement. I am specially indebted to the Rev. W.

Margam Jones, Llwydeoed, who has so ably translated Evan Roberts's poetical productions into English; to the Rev. Thomas Powell, Cwmdare, and Mr. David Williams, School Master, Tylorstown, for valuable help, and the Rev. David Davies, B.A. Miskin, Mountain Ash, who aided in reading the proofs and in transcribing. I wish to tender my sincerest thanks to all who have supplied me with information, and also those who readily let me have the letters of Evan Roberts to be published in the book.

Few errata have crept in, but are not of a misleading character.

Now, may God, the source of this awakening, make the history of Evan Roberts and his work, which has been written without avoiding any trouble to verily the facts contained therein, and with strict regard for truth, a means of grace to thousands is the earnest prayer of the Author

D. M. PHILLIPS.

TYLORSTOWN, July 24th, 1906

PART I.

The Preparation Of The Evangelist.

The Letter Of Dr. Torrey, The Renowned Evangelist, To Evan Roberts.

32, London Grove,

Princes Park Gate,

Liverpool,

November 29th 1904

Mr. Evan Roberts, Abercynon, Wales

Dear Brother,

I have heard with great joy of the way in which God has been using you as the instrument of his power in different places in Wales. I simply write this letter to let you know of my interest in you, and to tell you that I am praying for you. I have been praying for a long time that God would raise up men of his own choosing in different parts of the world, and mightily anoint them with the Holy Spirit, and bring in a mighty revival of his work. It is so sadly needed in these times.

I cannot tell you the joy that has come to my heart, as I have read of the mighty work of God in Wales. I am praying that God will keep you, simply trusting in him, and obedient to him, going not where men shall call you, but going where he shall lead you, and that he may keep you humble. It is so easy for us to become exalted when God uses us as the instruments of his power. It is so easy to think that we are something ourselves, and when we get to thinking that, God will set us aside. May God keep you humble, and fill you more and more with his mighty power.

I hope that some day I may have the privilege of meeting you.

Sincerely Yours,

R. A. Torrey.

Chapter I.

The Birth-Place of Evan Roberts.

1. THE IMPORTANCE OF A MAN'S BIRTHPLACE

Great importance is attached to the place where a man of fame is born. Should the place be unknown, it becomes the subject of close investigation and much theorising, and people seek for facts to confirm their suppositions regarding it. What is there in ones native place to create such interest? Its connection with him who was born there. When a man, in virtue of his character, his work, his heroism, his liberality, or his efforts in the uplifting of men, sinks deeply into their hearts, everything associated with him becomes dear to them, they love the path he treads. For the same reason the place where he was born becomes dear to them. The degree of interest taken in a man's native place is always in proportion to the degree of his greatness in a country or a nation's history. This is very plainly seen in the desire of men through the ages to see Bethlehem, the birth-place of the Saviour of the world. In a smaller degree, this is shown in the history of Augustine, Luther, Calvin, Bunyan, and Howell Harris, Daniel Rowlands, and W. Williams, of Pantycelyn, three great Welsh Revivalist's. Those who have read the history of these men, and are in sympathy with them, long for a view of their native place. To one class of people there is another thing that creates interest in the place where a man is born. It is this - the place partly conditions the form of a man's train of thought. As well might a man seek to escape from his own shadow as to escape from nature's scenes in the neighbourhood in which he is brought up. They give a colour to all his thoughts, and play an important part in the tone of his feelings, and the strength of his desires. A careful study of the neighbourhood in which a great man is raised would enable us to find out one condition of the characteristics of all his thoughts, and the modes of his mental developments. This is one of the branches the psychologists of the future will emphasise, for this must be done if we are to understand all we can about mental forms and mental distinctions. But it is not our part to do so in this connection. To give a picture, as real as possible, of the neighbourhood in which Evan Roberts was born, is our object. Truly, can it be said, that Loughor has been immortalised in virtue of his birth therein, and the momentous birth of the Revival. Henceforth, it will be named along with the most famous names of Wales. In ages to come pilgrims will journey to obtain a view of Loughor, and especially of Bwlchymynydd, and Island House - the home of the Revivalist's parents. Keen interest will be taken in the surroundings, and in every nook and corner of the house itself. No doubt great value will be set upon the stones and the wood of the house, and, who can foretell, to what regions of the world its photograph will reach - though it be but the photograph of an ordinary workman's cottage. All this is due to the fact that Evan Roberts has found his way to the dearest spot in the hearts of so many thousands in the land, and has caused a thorough moral and spiritual revolution in them. The history of the Revivalist will be handed down to the ages and the children of the generations to come, with warm hearts will hear and Iearn it from their parents on the hearth. They will be desirous of knowing all they can of the neighbourhood and the house where he was born; and their parents will strive to describe them, until their hearts will be on fire with a yearning to see them. Look down across the generations of the future and you will behold godly people on their way to see the place in which was born the hitherto greatest Revivalist that Wales has produced. In saying this we are not unmindful of the Revivalist's of undying fame that the nation has raised in the past Yet, having given them all due consideration, we must admit that the country was not stirred by any of them to such an extent as it has been by Evan Roberts of Loughor. In the whole of its history, Wales has not experienced in six months such a mighty moral and spiritual upheaval as that brought about though his instrumentality. For this reason, none can tell the measure of men's desire for seeing Loughor and Bwlchymynydd in ages to come.

II. ANCIENT LOUGHOR

Looking into the primitive history of the town, we find that it was a place of no small importance in the time of the Roman Conquest. The ancient Britons had a strong fortress here, the town being called Tre'r Afanc (Beaver's Town). That it was a place of note under Roman rule is shewn by the fact that it was the fifth station on the Roman road called Vià Julia, and the 'Lecarum' of Richard of Cirencester. Later on we find it possessed by the Kymry; then by the Irish under their Prince, Gilmor Rechdyr. The Irish, however, were not destined to a long rule. The Welsh summoned King Arthur of Caerleon to their help, be defeated them, an made Urien, his nephew, Prince of the district, which was now called "Rheged." He was followed by Pasgen, Morgan Mwynfawr, and Owen, the son of Hywel the Good. After the reign of Owen, the place became the scene of many battles, and much bloodshed, caused by the rivaly of the Princes of Glamorgan. Next we find the Normans in possession of the town, and they build a fortress there. Again the town falls into the hands of the Kymry, only to be retaken by the Norman Barons. Eventually, in 12 is, Rhys, Lord of Dinevor, attacked and destroyed the fort, together with all the fortresses in Gower. This part of the country was then given to Edward II by Hugh Le Spenser. At great expense and trouble the fort was rebuilt, and the remains of its walls can be seen today at Loughor. From these facts we see that Loughor was once one of the most important places of defence in the land, and a scene of much shedding of blood. But it must be borne in mind that, whereas, Loughor of ancient and medieval history was noted as being the dwelling place of Princes skilled in the cruel art of war, its name now arises from a far different source, it is famous as the birth-place of a man, who is a Leader of the Army of the Cross. His followers number their thousands, and not hundreds, as did the followers of the old Princes who dwelt in the Castle in the days of yore.

III. MODERN LOUGHOR

It is thought that there is a vast difference between modern Loughor and the one described above, men are of opinion that the present town is not built on the same site as the former. Tre'r Afanc is supposed to have been situated on what is now called The Borough, and the church on the spot called "Story Mihangel." The present town is small compared with the old; it stands on the highway road from Swansea to Carmarthen, and near the rail-road from New Milford to London. It is 211 miles from London, 50 from Cardiff, and 8 from Swansea. The town and the parish are in the canton of Swansea, in the Deanery of Gower, the Arch-Deanery of Carmarthen, and the Bishopric of St. David. Though the town is not so important at the present time as it formerly was, its advantages today excel those of the past. Now, there is a station here on the Great Western Railway, making it possible to reach the furthest parts of the land from Loughor in a very short time. We find here a Post Office, a Saving's Bank, and a Telegraph Office, so that the town is not lacking in its advantages in this respect, small though it is. The means of crossing the large river are greatly improved upon what they once were, the men of former ages crossed in a boat, but now the river is spanned by a fine bridge, two hundred yards long. The railway bridge, a little lower down, however, measures a quarter of a mile. The river Loughor forms the boundary line between the Counties of Glamorgan and Carmarthen. The town has a Public Hall and a Police Station. It has three Chapels as well as a Church of England; those belonging to the Calvinistic Methodists, the Congregationalists, and the Baptists. Taking the population into account, these are in a fairly flourishing state. In the last census that we succeeded in finding, the population numbered 2,064 within the Borough, that of the whole parish being 4,196. The part of the parish within the Borough measures is 9 acres, while there are 48 acres under water when the tide is in. Outside the Borough, and taking in the agricultural district, which comprises Gower, we have 2,489 acres. Though the river has 14 feet of water when the tide is full, the road and railway bridges make it impossible for large ships to enter the port. As early as is 37, Loughor was made a Borough of the Cardiff and Swansea Union, and remained so until 1832. From that time until 1886 it was a Municipal Borough, joining with Aberavon, Neath, and Kenfig, and a part of Swansea, in sending a member to Parliament. Beyond the river there are tin works, while there are several coal mines in the neighbourhood. The number of these works seems to be increasing, but not through them will the name of Loughor be handed down to future ages. Something far different from these will make it immortal, as we have stated at the beginning of the Chapter. At the time when the Castle was last rebuilt, and for centuries afterwards, the neighbourhood was rich in scenes of natural beauty. Then, the picturesque surface of the land had not been marred by a railway, neither by zinc works, nor a coal mine. In imagination we can see the leafy groves, the trees laden with fruit, and the beautiful flowers that cover the ground around the place, the animals grazing in the meadows, the birds on the boughs carolling sweet songs of praise to their Creator. One after another the generations come and go, without the appearance of any one whose fame becomes known throughout his own nation, not to speak of world-wide fame. The centuries roll on, and Loughor is only a name spoken in common with other names in the County. Though the neighbourhood is beautiful, it is not so exceptionally picturesque as to distinguish it from other places in Glamorgan. Situated as it is in the extreme part of West Glamorgan, and being small in comparison with the other towns, its chances of winning fame were small. Passing through Loughor Station the traveller feels no inclination to look out from the window to see any wonderful building or scene. Did one happen to look out he would behold nothing particularly attractive. No one is amazed at the sight of the old Castle ruins, for it is small as compared with some of the large castles of Wales. Now, however, there is a great change when passing through Loughor Station, those who have heard Evan Roberts, those who have read of him and are in sympathy with him, strive for a full view of all they can see. I have seen mother's holding children, three and four years old, out to obtain a complete view of everything they could see from the station. What accounts for such a change? Nothing in the town, nor the surrounding country; but the fact that Evan Roberts and the Revival of 1904, in its sweeping form, were born there.

As has been mentioned, the town is a small one, but some scores of years ago it was important as a port. Large numbers of ships were built here, hence, timber was brought in from different directions of the surrounding country. The lower part of the town stands on a small rising near the railway, as remarked above. It was well that it was on a hill in olden times, for the sea came in and completely encircled it. By the present time the sea has gone back. The upper part stands on the slope some distance from the lower part. The town has no form after the manner of towns of late years. We find here a number of old houses, but not more than from two to six of them are joined together. So it may be said of houses built in later years - two here and two there, three in one place and four in another. You would not find a street of twenty houses in the town. From this partly arises the variety that is seen in the place. The sight of an occasional thatched cottage in the vicinity of the town gives one an indication of what Loughor was centuries ago. It seems that every one chose his own spot to build a house, and sought freedom around it. In passing through, one perceives that variety is the distinctive feature of the town. This applies equally well to the whole neighbourhood. We may look in any direction we please, and we shall not see uniformity in the scenery. Seldom do we find a perfectly quadrangular field in the neighbourhood, nor shall we find an even one. We are compelled continually, owing to the unevenness of the ground, to change the position of the eye-axes in order to obtain a full view of a scene. The parish has no high mountain nor a large plain. On all sides are seen small hills and dales rich in variety. As in the case of the ground, so with the flowers, hedges, and trees: flowers of many different colours, variegated hedges, trees of different sizes, and we behold a good number of them in different directions. As compared with some districts in Glamorgan, we can say that Loughor is woody. Were one asked for a word that sets forth most effectively the characteristic of the town and neighbourhood, Variety would be the best word by far.

Now, let us direct our gaze outside Loughor, what is the sight that meets the eye? Variety again. Towards the south-west, we behold the Loughor River, giant-like in its all-conquering career from its source in the Black Mountain, entering the Severn Sea. A little more to the south, across a corner of the Channel, we see the village of Penclawdd with its tin-works; while behind it is that fine tract of land called Gower, where the Reverend Sire W. Griffiths of Gower ministered. The admiration felt by the inhabitants for Mr. Griffiths, owing to his undoubted piety, was little short of worship. Looking to the south-east, situated in a beautiful spot, on the rail-road to Swansea, we see Gowerton. Turning our eyes again a little to the north-west, the tall chimney stacks of Llanelly. Tinworks in Carmarthenshire appear before us. In this direction we get an extensive view, full of variety. Looking northwards, Llangennech and Pontardulais, and the valley of Loughor, are seen. The scenery in this vale in midsummer is beautiful. In this pretty dale dwelt David Williams of Llandilo Minor when he composed the immortal hymn -

In the deep and mighty waters,

None can save and succour me,

But my dear Redeemer Jesus,

Crucified upon the tree.

He's a Friend in death's deep river,

O'er the waves my head he'll guide,

Seeing Him will set me singing,

In the deep and swelling tide

A mile and a half in the north-westerly direction stands the village of Gorseinon. This cannot be seen from the town of Loughor, for a hillock stands between them. It is a village of recent growth, owing its existence to the large coal mine sunk close to it. The Revival has made it famous amongst other villages in the county and in Wales. Wonderful things took place here at the beginning of the Revival, as we shall point out in another chapter. Before we can adequately describe the marvellous mission of Evan Roberts, we must ever closely connect Gorseinon with its beginning. To the south-east stands Swansea, but not in sight from Loughor.

IV. BWLCHYMYNYDD

We have named the chief places in the neighbourhood of Loughor, as well as described the place. We now come to Bwlchymynydd and Island House Bwlchymynydd a mile to the north from Lower Loughor, having the same characteristics as Loughor - a few houses scattered here and there, and variously built. Here we find Pisgah the little chapel in which Evan Roberts worships. It is a branch of Moriah, the Methodist Chapel of Loughor. We shall have more to say of Pisgah again. Having come to the village of Bwlchymynydd, we keep to the left for some fifty yards, then turn to the right, and having walked on a few hundred yards, we arrive at Island House where our subject first saw the light of day. On the way to it we pass the well called The Well under the Field, which supplies a great part of the neighbourhood with water. In another chapter will be told an account of a strange incident relating to Evan Roberts in connection with this well. A large brick wall has been now built around it, making it visible a great way off. The writer was present on the spot with the Revivalist Christmas-time, 1904. A man drove up to the well, and was accosted by Evan Roberts in the following words, You carry water to quench the natural thirst of people. I do my best to quench their thirst with the living, spiritual water. As soon as we have passed the well, we are quite close to the house, which faces the west. It is not on a main road, but on the side of a narrow lane that runs before it. It is a few yards from the road, and at the north corner we find the entrance towards it. In front of the house a few evergreens add to the beauty of the scene.

Near the upper part of the spot is a small green, through which a path leads to the back of the house. On this green stands a tree planted by Evan Roberts with his own hand. Behind, and a little to the south, we see a large garden excellently cultivated. As we draw nigh to the house, what strikes us first of all is the absence of every kind of waste.

Nothing is to be seen save what is necessary to make life pleasant. Things that are absolutely essential, and nothing more, do we see outside the house as well as within. Yet, we find here many things that prove the inhabitants to be possessed of a taste for the good, the lovely, the beautiful, and the sublime. Outside and within can be traced the marks of a desire for neatness and cosiness. We think that neatness is one of the chief characteristics of the father and mother, and the children too. The house is a remarkable instance of what a working man's dwelling should be. It contains eight rooms, which, though not large, are so neat that one feels quite contented and happy as soon as he sits in one of them. As we go to Evan Roberts's Library, which is on the left as we enter, we see at once that the family is one that loves the good. This will become more manifest when we have occasion to speak of his Library. When once seated in the house, perfect silence characterises the place. No sounds are heard except the melody of the birds on the boughs about the house. Let us go out in front of the cottage and over against the way is seen a marshy swamp, and beyond that again, there arises a green meadow, called the Great Island. Some recall the sea at high tide coming up and surrounding this meadow. Such a sight not improbably gave the field its present name. Which-ever way we look from the door of Island House, the scenes that meet the eye are characterised by variety. What wonder is it then that he who was born here is so rich in variety in his mind and in his work? At a distance of a few miles from the house, we may behold every scene that Nature can give us; on this side, the surging sea, in the distance behold high-peaked mountains. Nearer to us we see picturesque hills and a broad plain, rich dales and marshy bogs; thick hedges, stout and tall trees; multicoloured flowers, thorn trees, and gorse, and the smoke of mines. We hear the puffing of the steam-engine; see a large river and little streams; narrow winding lanes, and a main road, almost free from so many turnings. It were impossible for a great rich mind not to develop rich in variety in such a place, for it could not but produce in it ideas of different kinds. If we bear in mind the variety in the scenery of the place, it will help us to understand the variety that belongs to Evan Roberts's mind, feelings, and desires. As far as we are able to describe them, these then are the Loughor and Bwlchymynydd where he was born and reared, whom God used in 1904 to move all Wales morally and spiritually.

Chapter II.

The Heads of the Family of Island House, Bwlchymynydd.

We described the house in the previous chapter, we come now to the family heads. Henry Roberts, the Revivalist's father, was born at Loughor. His parents were David and Sarah Roberts. He was born in 1844, so that he is now drawing towards 62 years of age. Throughout the years he has worked hard and perseveringly as a pump man and a collier.

His effort to bring up a houseful of children so respectably, and giving them all good elementary education, is very praiseworthy. He is rather tall, but not stout. Hard work has left its marks upon him, and we note that he has not so much eaten his own bread through the sweat of his brow, but has brought up a large family through much sweat. His face tells us that he is a man who belongs to the nervous temperament class.

It is from this class most often men of great talents arise. They are alive to all their surroundings, and open to deep impressions. The enthusiasm of their nature makes them daring in speech and action, whatever may be the consequences, and they learn much from their mistakes. His eyes and face show that Henry Roberts is of an excitable, lively, and fiery temperament. This temperament is an excellent one, if kept under control, and if accompanied by a high degree of intellect. We must have active and sensitive nerves in order to think rapidly, clearly, consistently, and deeply. This is the temperament that sets the world moving onward.

It is the chief element in its development. Henry Roberts may be grateful that he possesses a lively and electric nature. Without it he would never have found food enough for a family of ten, and to become the owner of his own house as well. He must know what it is to be loaded with burdens and cares. Yet he did not let religion suffer as some do. He acted honourably and faithfully with the great cause throughout the years, and his contributions were such as might be expected from one in his position. This speaks highly of his religion, his good nature, and liberal spirit. His two dark eyes point to loving kindness as a characteristic trait in his nature. This is a peculiarity that belongs to the majority of enthusiastic men. From the photograph, we see that he keeps his beard, which like his hair, is now almost grey. Though he has seen his sixty-first birthday, yet his movements today betray the once smart and sprightly youth, who could accomplish much in a short time. His one book during his lifetime has been the Bible, which, with religion, has been the subject of conversation on the hearth throughout the years. What wonder is it then that great things have come out of his family. Not only he has been a great reader of the Bible, but he has committed much of it to memory.

When young, he learnt no less than 174 verses in one week. He made it a regular practice to learn a portion of God's word daily in his early days; hence he is well versed in it. Henry Roberts is interested in the topics of the day, but to him religion is the centre of all. Like his son, Evan Roberts, he, too, has an eye that sees the humorous, and his nature is alive to this aspect of life. When I asked him one day, 'How is the family with you?' he answered, 'We are fairly well, we have food enough here, and also an appetite for it'. There was an old man here years ago, continued Henry Roberts, who called in a house where the inmates were very poor.

He enquired, as you did now, after the welfare of the family. 'Very poor', was the answer. 'Things could not be worse, for there is not a morsel of food in the house.' 'O!' said the old gentleman, 'yon could be in a much worse condition than that. You might have had plenty of food in the house, and none of you having an appetite for it. That would be the time to say that things could not be worse. Henry Roberts's eyes sparkled with humour as he related this incident.

Hannah Roberts, the Revivalist's mother, was born and brought up the first years of her life in a place called The Smithy, a quarter of a mile from the main road from Llanon to Llanelly, in the parish of Llanelly, Carmarthenshire. Her parents were Evan and Sarah Edwards, her father following the occupation of a blacksmith. He was of a quiet disposition, had an irreproachable character, and was a spiritually-minded man. He was a faithful member and musical conductor for many years with the Baptists at Llanon. Previous to his marriage, he was a Calvinistic Methodist, as well as his parents before him. But he thought that it was better for him and his wife, who was a Baptist, to go to the same place of worship, hence he joined her. His house was a home from home for all the ministers that came to the place to preach. He refused the office of deacon, because he felt he did not possess the requisite qualifications; the Church, however, felt otherwise, and besought him to accept it. The young people held him in high esteem, and on Sunday evening after the service, they looked to him to learn singing. Soon after Hannah, Evan Roberts's mother, was born, the family removed to the Smithy, Llanon, where they lived for 24 years. About 35 years ago, they came to Pontardulais, and there Sarah Edwards, the Revivalist's grandmother, now dwells. She is 92 years of age and still faithful with religion.

Throughout the years, she has acted as midwife, and is highly respected by her friends. She says that Jesus has been so good to her during her long life that she has resolved to hold fast unto the end. It must be said that she is far above the average in mental capacities. Her memory is wonderful for its grasp, firmness, and clearness, considering her age. She holds strong views on baptism by immersion, and this is her only cause of disagreement with her grandson, the Revivalist. In character and conduct, she is spotless and has always been noted for her religious fidelity.

It was on January 8th, 1849, that Hannah, the Revivalist's mother, was born, being the seventh out of nine children. When 14 years of age, she agreed to go into service in Loughor. She did this without her mother's knowledge, for she was not pleased with the place that her daughter was going to In a years time, she returned home. Soon after this, she agreed to go to a place called Cwmhowel, to a Mr. Peel. At Loughor, she first met her husband, and on March 31st, 1868, they entered the bonds of matrimony. She is of a somewhat quiet disposition, and one can easily see that she has a will of great firm. Not for anything will she say yes, when she ought to say no. She is a woman of meekness and prudence with a moral sense of a very high order. Her talents in more than one direction are far above the ordinary, as we shall presently point out. In the chief facial lines, we detect a great similarity between the mother and her famous son, Evan Roberts. The more one gazes at her, the more do these lines become manifest. All the characteristic facial lines of her son are seen in the mother's face, but in a lesser degree, especially those that indicate a resolute will and firm determination. As to height, she is not tall, but medium, neither is she stout. She has two lively and loving eyes and a pleasant face, full of thoughtfulness. Words are not wasted by her, though in conversation she is ready, free, and outspoken. She is not very sprightly in her movements, but she is not long in accomplishing the task set before her.

As Henry Roberts is an example of what a father ought to be, so with Hannah Roberts - she is an example of what a mother should be.

Although her children numbered fourteen, eight of whom are still living, she brought them up neatly and honourably. The young wife, after her marriage, set about to learn cutting and sewing, so that she has not paid for making clothes for any of her children when in their first years. At the same time, she cared for her husband, and her house was always cosy, neat and clean. Thus to learn about her marriage proves that she is endowed with perseverance of the first order. Her children were sent to the services on the Sabbath so clean and becoming that she was not ashamed for anyone to see them. In the evening on the Lord's day, behold the parents with their eight children on the hearth in Island House. They sing a hymn together, and are as happy, nay, more happy, than the Royal Family. A glance at Island House will show us the common sense of Mrs. Roberts. Three things are to be seen here that at once point to this. Firstly, nothing is noticeable save what is really necessary in a house to do the work and to be happy; secondly, these things are in their proper places, and, thirdly, everything is clean. On all sides we behold the result of wisdom, hard work, neatness, and order.

With her too, like her husband, the Bible is the great book, and she continually makes more of it as the years roll on. Of late years, she has learnt a great deal of it, and the children have followed her example. The many certificates that hang on the walls show that the Sunday School Examinations are high in their estimation. By committing the appointed lessons to memory, the mother drew the children to imitate her. They have also treasured the Bible in their minds. Besides being a mother and a wife of the best kind, Mrs. Roberts has also a strong moral character.

When making enquiries with regard to her son, I asked her if one particular thing attributed to him was true. It is not, she answered; I hope nothing of the kind is spread abroad. I have always been careful about the truth; but I have never been so careful as at present, being that everything is put in print. I would not like to see a single word appear that was not true, because it is truth that will stand. What I was enquiring about was a matter that did them honour as a family, and I greatly admired her for rejecting it, as it was not true. Who can measure the moral influence of a mother such as this upon her child in this respect.

Evan Roberts is a perfect reproduction of his mother. He swerves not from the truth though the whole world brought its influence to bear upon him. Much of the praise for this is due to Hannah Roberts. Unless the mother respects Truth, only in very few cases will the children do so. Not only has she a strong moral character, but she has clear ideas about principles that require a power to penetrate into the heart of things, before we can fully understand them. When talking to her one day, the conversation turned upon those who opposed her son, and she made one of the most searching remarks that I have ever heard on a matter of this kind. It is a great pity for them, said she; it will be to their own loss. I have no fears as to Evan: for I know what he is from childhood. I am certain that he is conscientious, and that whatever his failings are, he does all from pure motives. It is to be regretted that anyone should wrongly explain him. I hope they will see things as they are, and that God will forgive them. Seldom will we find mother's of such a spirit as is manifested in these words, when speaking of those who without cause opposed her son. It was easily seen that it was for these persons she was sorry, and not for him. Many a mother, however, would speak of them in merciless terms, seeing her son on such a height of fame. Not so did Hannah Roberts deem it becoming to do. No wonder she is so sound in the principles of practical morality, for she acts these in her everyday life.

Notwithstanding the fact that her parents were Baptists, she has never been a member only with the Calvinistic Methodists. She went with her husband to Moriah, the Methodist Chapel at Loughor, and were made members the same night. Since, they have always been faithful with all the movements of their church. Henry and Hannah Roberts are a simple and humble pair. They lay no claim to an illustrious pedigree nor famous relations. When I asked them whether any men of fame had appeared; amongst their forefathers, they desired to affirm no such thing. Their aim is to let everything stand on its merits, seeking nothing that would for a moment win for them the applause of the public.

As we have mentioned before, fourteen children were born to them, eight of whom are living; and when we remember this fact, it is wonderful how they have borne up so well. Who knows the care and anxiety of their minds when rearing the eight now living? That their care was great and their anxiety intense is certain. The mother's heart leaped with joy as she informed me that not one of them had ever given her trouble. My heart was filled with delight when bringing them up, said she. I would stay down late to sew and mend their clothes, so that I might follow my duties in the day. Without this it would have been impossible to bring up eight children, with no servant to help her. Evan Roberts is the ninth of all the children, and the fifth of those at present living. Two of his sisters reside in America - one married, the other single. In another chapter, we shall have a word to say regarding those in this country. The following are the names of the children in order of age - Sarah, Mariah, Catherine, David, Evan, Dan, Elizabeth and Mary.

And now Henry and Hannah Roberts have lived to see one of their sons the centre of attention and attraction of all Wales, and to a measure of all Christendom. For all that, there is in them no unworthy delight. Rather do they glorify God in His Son for such an inestimable privilege. When the Revival had broken out with power, the father one day, standing at the comer of his house, observed of Evan and his other children who had been fired, 'Here they are in thine hand, Lord; do with them as thou wilt'.

Thus, Henry and Hannah Roberts shall be accounted blessed amongst fathers and mothers in Wales, because of the high favour shewn to them in letting them bring up a child so manifestly used of the Spirit to give the greatest blow to sin that has been given for many years past. They see their reward for allowing religion to be the chief subject on the hearth, and the Bible the principal object of study. They see the result of setting a good example before the children at home, they have happiness in their heart which more than repays them for all their efforts to bring up eight children. Oh! what spiritual delight there is to these parents at the close of their days on earth! With the Psalmist of old can they say - 'Thou hast put gladness in my heart more than in the time that their corn and their wine increased.'

Chapter III.

The Day of the Possibility.

The 8th of June, 1878, was a great and extraordinary day in Island House, Bwlchymynydd. It was so because on it Evan Roberts was born. In the history of the family, the neighbourhood of Loughor, and Wales as a whole, we can rightly call it the 'Day of the Possibility'. On that day was born one in whom lay the possibility of creating a religious revolution in a whole nation, with the Spirit of God using him as an instrument. Yet, this was not known to anyone except the Divine Persons, and possibly some of the angels. And so his birth was in the manner of every child's birth. It did not cause the inhabitants of the place to leap with joy, but angels, maybe, sang. Were they told of his future, then surely they sang and rejoiced, for they could see how much there would be for them to do in connection with him. The parents, no doubt, looked upon their newlyborn babe as one who in years to come would be a help and comfort to them; but God regarded him as the embodiment of possibilities to be used in the Spirit's hand to bring thousands to repentance. A wondrous day, truly, is the birthday of many an one. Untold possibilities come into being at the same time. On a smaller scale, the birth of every morally great man may be likened to that of Him who was born in Bethlehem.

The birth in the manger in Bethlehem was simple enough and unknown to the world at large, but then, there came into existence the possibility of saving an unnumbered multitude of sinners. Through the birth of Evan Roberts at Bwlchymynydd on that day, there came into being a possibility which will be instrumental before the end of time in bringing millions to the Man who brought into being the possibility of Salvation, by the birth in Bethlehem and the death on Calvary. The result of the work of Evan Roberts will go on through the ages, and some of them will be effective in the end of the world. When his mortal part is buried, his works will go on and multiply forever. The possibilities of every life are wonderful given favourable conditions, they will increase, and so continue their existence. As we ascend in the scale of life, the possibility increases accordingly. The highest life has the greatest possibility. On earth, man is the creature that has the highest and richest life; hence, his is the life with the greatest possibility in it. Among men we find degrees of possibility, in the sphere of mind, affections, and actions. The majority possess but average possibility, and rise to no distinction in any department of life. From this class up to those who possess the highest possibility, we have every grade of intellectual power that we can think of. Those who have the greatest possibility contribute to the world's development in various directions. They make the world move on from the old lines in the different branches of knowledge, religion, morality, and spirituality. They cut out paths for themselves, and will not be governed by public opinion, which becomes disturbed once it sees new ground being possessed. We make bold to say that the babe who was born at Island House, Bwlchymynydd, on the afore-mentioned day, belonged to this class. He had the possibilities of a spiritual life that were extraordinary, the possibilities of a man of the highest genius in his class - possibilities, as we shall again see, of cutting a path for himself without consulting anyone save the Spirit of God.

Who would think that such a possibility lay within him when a child?

Did the midwife for a moment think of his tremendous possibility? No, she saw nothing in him different from other children. She would tremble to hold him in her arms did she know of his possibility and his future.

Were his work with the Revival known on his birthday, many of the old saints of Loughor and of Wales would have readily gone to his parents house, saying with Simeon of old, Lord, now lettest thou thy servants depart in peace, according to thy word, for our eyes have seen one who will be used of Thee to bring Salvation to thousands in Wales. Many have been the desires, intense the prayers offered up for a Revival, but at last we have its instrument in our arms. Hundreds have journeyed to Loughor during these last months in order to see Evan Roberts, his parents, and the house where he was born; but had men known of his possibility at his birth, the visitors to the place would have been far more numerous then than now. As is His wont, with every great possibility, God hid this from all. Men wonder at the possibility when it has been revealed. This is what He has done in the case of Evan Roberts.

We see his mother nurse him, a tender child, without seeing anything exceptional in him, save his loveliness. Every mother thinks her child lovely; and it is well that she does. It shows how great a mother's affection is for her child. Hannah Roberts carries him in her arms, little thinking that she has a treasure so great. Gazing at his face in the cradle, the thought of his possibility does not enter her mind. As she rocks the cradle, far from her thoughts is the idea that in it lies one destined in less than twenty-seven years to move a nation in religion and morality.

Behold two little hazel eyes brightly gazing at her, whose glance now thrills vast assemblies of men; but she does not foresee this. Lovingly does she kiss her little ones lips, little thinking that the words that would pass from his mouth and Iips would hereafter fix the undivided attention of the multitudes upon them. She is quite unconscious of the fact that the lovely face she presses to her cheek will one day be charming men with the heavenly smile that flickers across it. Far from her mind is the thought that the fat little arms that now embrace her will be waving in Welsh and other pulpits, and that multitudes will follow their movements. No, she did not dream that the little feet and knees then too weak for walking would again be gliding from place to place to proclaim the eternal gospel; and walking though the chapels to persuade some to receive Christ; to comfort others in their sorrow, and to warn many of their perilous state. Be that as it may, in the birth of our subject there was born to the nation a wealth of moral possibilities to be used by the Spirit of God to do spiritual wonders yea, things incredible to any but spiritually-minded men.

Let us once again look upon him when a babe. What is there in him?

Everything that has developed and will develop in him. All the germs of his powers lay in him when first he saw the light of day. Whatever the grace of God has done and wilt do with his powers, all the possibilities of those powers were in him in his childhood. Wales today can sing 'Precious treasure was found in Island House, Bwlchymynydd, June 8th, 1878. There is reason for saying that for ages long the day of the dawn of the Revival will be commemorated, but there is more reason why the birthday of Evan Roberts should be commemorated. It was this day that made his connection with the Revival possible. Heaven looked upon the day of His birth in Bethlehem of more importance than any other day in the life of Christ. This is shown, firstly, by the great joy that was there among the angelic hosts, who winged their flight for the first to the Judean fields to sing their carol - 'Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace, goodwill toward men,' secondly, the day of the Incarnation made possible the death of the Cross. The Incarnation of Christ contains the possibility of the Atonement. All that Jesus did in His life arose from the possibility that was in Him as a babe in the manger. The same truth holds with regard to the works of Evan Roberts, they are all the outcome of the possibility that was in him in the cradle. Were a serious consideration given to the fact that children possess all their possibilities at birth, parents would be far more careful in dealing with these possibilities during the first years of their children's life. The rule is that the entire course of their lives is determined by the treatment given to their possibilities and powers during these years.

When the proper time came, our subject was baptised in Moriah Calvinistic Methodist Chapel, and was named Evan John. This was the name by which he was known by the people of the neighbourhood. By today the name John is scarcely heard; he is known simply as Evan Roberts. He does not any more wish to be called John, but only Evan Roberts. We heard him say at Hirwain that he had written it for the last time. In this too, as in other things, he desires to make use of as few words as possible. His name will go down to future ages as Evan Roberts, and not Evan John Roberts.

Chapter IV.

The Blossoming of the Possibility - Evan Roberts When a Child.

In the previous chapter, for particular reasons given there, the birthday of Evan Roberts was called the day of the possibility. For the same reasons can his childhood be called the blossoming of the possibility in this period we find the wealth of his natures possibility beginning to open out. It is a misfortune that we have not the details of this period in our possession, for they would be of special interest. This is the time when the mind reveals many of the inherent characteristics of its possibility. It breaks forth in the strength of its own energy before it is conscious of the meaning, the nature, and importance of its actions; before it is conscious that its actions are noticed and criticised. The first acts of the mind are a kind of natural and unconscious outburst, but this outburst takes place before a man is able to reflect upon his mental activities. Hence, Evan Roberts knows nothing of this period in his life. His parents and others never thought that his biography would be written: for this reason, they did not carefully note his distinguishing, peculiarities when a child. Yet for all this, we are not entirely ignorant in a general way of our subject during this time, because the Evan Roberts of today is only the fruit that has grown out of that period. Whatever his special characteristics now are, they are only a higher development from the blossoming of his possibility when a child. To seek for all the activities of his mind and the contents of his consciousness in the years of the blossoming of his possibility would only be satisfying curiosity. All their principles will be found in him now, for life carries with it the instincts of its past. In some form or other the whole of Evan Roberts, the child, is seen in Evan Roberts, the Revivalist. Here we get his thoughts, his feelings, his imagination, his conscience, and childish desires. Without this there would be no unity in life. The only difference is that these things are characterised now by a development higher than when he was a child.

The point wherein we are at a loss is that we do not see them in their undeveloped state as they were then. We are assured that there was nothing in him as a child to draw special attention. It may be safely said that the things which marked him out from the time that he began at school until he was twelve years old are before us. These are the interesting things, and not those in him which were common with other children. In order that we may the better see the blossoming of his powers, we can classify them under different headings.

I. EVAN ROBERTS AT PLAY

One of the most effective things to reveal the characteristics of a child is his manner and spirit at play. Evan Roberts used to play like most children do, that is, he was full of the playful spirit, and not timid and lifeless as some children are. We can imagine him as a boy with light curly hair waving in the breeze playing near the house and in the adjacent fields, and paying an occasional visit to the large island, in order to gaze upon the Loughor river and the sea coming up to meet it. Oft while at play, he would stop in the middle of a game to listen to the birds singing, for this delights him to this day. In his play, we find elements that are not commonly found in children, and these remain in him still.

He could not look upon any of his playmates suffering. When this happened, the joy of playing was gone for him. That was no play to him where all were not joyful. To Evan Roberts the essential element in play was that every one shared the same happy feelings with him. His liberality was clearly in evidence in his games, and with a willing heart would he share his good things with his companions. He put all his energy into his play; showing his thorough conscientiousness in it all.

Deceit and treachery even at play grieved him. At all times he is seen to strive to be consistent in word and action, and one to be relied on. He would willingly lend a helping hand whenever he saw a playmate in difficulties and unable to do anything that he could show him the way.

The first two characteristics that his mother remembers in him are helping others and striving to make everybody happy. He was possessed then of the true spirit of a player.

II. EVAN ROBERTS AT SCHOOL

Between four and five years of age, we find him at school. Hitherto, the possibilities were allowed to blossom without any permanent external influence, save that of his father and mother. Now, he is in a sphere where he must conform with fixed rules. We can hardly believe that a child of so independent a nature as Evan Roberts found it easy to bend under these for some time. He is not long before manifesting a capability of learning with rapidity. He stands with the best in his class. One year, a book was offered as a reward to the best in the class, the competition lay between Evan Roberts and another lad. In the final test, he won the prize.

But after going home, Evan wept bitterly because the other boy had not received a book too. This shows that while he was yet young, there were in his nature wonderful liberality and magnanimity. One would expect him, in accordance with the natural and common tendency in children, to rejoice, and boast of having won in the contest. But his heart would not allow of that. It grieved him sorely to think of the disappointment of the young friend going home without a book. This was but the manifestation of the glorious blossoming of the possibility of his nature. It is to be regretted that he was not allowed to remain in school. Had he remained, we doubt not that that he would have become a first-rate scholar. His progress in education during the few years he spent at school is enough to prove this. Mr. Harris, his school-master, testifies that young Roberts was most fond of his books, and through his close attention to them reached the sixth standard before he was twelve years of age. During this time, he was full of play; but nothing rough characterised his playfulness.

A schoolmistress, with whom he was for some time, states that he was her chief defender, when the children were unmanageable he would argue with the children the consequences of being naughty, and as a rule succeeded in quieting them. Owing to circumstances to which we shall again refer, he was obliged to leave school three months before he reached his twelfth year. He did this, as is the case with the majority of children that belong to the working class, in order to earn his living through the sweat of his brow. He was not compelled to do so by his parents, but he wished it himself.

III. HIS BEHAVIOUR TOWARDS HIS PARENTS.

During this period the strong and living affection that he still feels towards his parents is manifested. His obedience to them was perfect, springing from a willing heart; and, therefore, was but the expression of his affection for them. He was never heard to say No to either of them.

When eleven years of age, a splendid opportunity was given him of showing his strong affection towards his parents. At the birth of his youngest sister, Mary, his mother was dangerously ill, close upon death.

This called for Evan's frequent services as a messenger. He would run full speed when sent on an errand, stopping in no place, however much the temptation to play. His love for his mother was stronger than the playful inclination. Of his own accord, unasked of any, would he do this, being induced by the highest motive, namely, love for his parents. We can easily see that his rule of conduct then, young as he was, was obedience to the promptings of the highest powers of his nature. This is the burden of his preaching today: obedience to all the promptings of the Spirit of God. His willing obedience in the first years of his childhood was an effectual preparation for the time when the Holy Spirit came to invite him to surrender himself completely on the altar of service to Jesus.

During this period he nursed his youngest sister a great deal, in order to help his mother. Mary Roberts says that were she then able to think and to speak, she ought to have known much concerning her brother at that time. He was ready to do anything within his power for his parents, whether it were customary for his companions to do so or not. When about eleven years of age he undertook to dig the large garden attached to Island House, in order to spare his father, who was in sore trouble at the time, owing to the illness of Mrs. Roberts. In a few days he had accomplished the task, great as the labour was to a lad so young. He clung to the work with the energy and determination of one resolved to conquer,

IV. THE BLOSSOMING OF HIS HABITS

His possibility of forming habits is revealed in these years also, for we discern two very prominent features in this at this period.

Order - He delighted in arranging everything that came in his way.

His purposes were always neatly planned and executed. This was made manifest in his play and his work about the house.

Cleanliness - To be clean was ever one of his chief aims - clean in dress, in words, in work, and in conduct. Applicable is the old adage to him: 'Cleanliness is next to godliness.' Those children who are careful as to order and cleanliness in the things mentioned above, as a rule, will not find it difficult to reach true godliness. These were the result of his own nature, and not the fruits of culture. Though his parents were strong in these matters, they had not to advise Evan to be likewise, for he was so already. They grew naturally out of him. We may add one more habit to the foregoing -

Gentlemanliness - He always replied and addressed people like a gentleman, while his general conduct from childhood was marked with perfect good manners. His elders were always impressed with his excellent behaviour in their company. We have good reason to expect great things from children in whom habits such as these are seen to blossom.

V. THE BLOSSOMING OF HIS PRESENCE OF MIND AND HIS FAITH

We find him possessed of extraordinary presence of mind when from seven to eight years old his brother, Dan, fell headlong into the well that was near the house, and would have met with immediate death had Evan not been there. Hurrying to the well, he seized his little brother's feet, and pulled him out in a few seconds. He must have had presence of mind to act thus, when there was no one near to tell him what to do. Many a child, would become terrified, and lose all self control at the sight of his brother in such a plight.