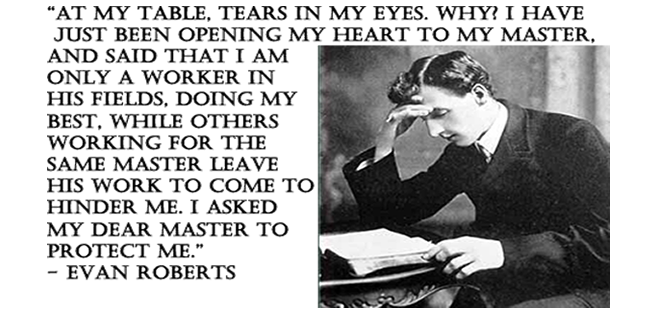

EVAN ROBERTS

By Gwilym Hughes

EVAN ROBERTS, REVIVALIST

Story Of The Liverpool Mission

by Gwilym Hughes

(Special Correspondent of the "South Wales Daily News")

WITH A SPECIAL ARTICLE ON THE REVIVALIST AND THE

MISSION BY SIR EDWARD RUSSELL,

Editor of the "Liverpool Daily Post and Liverpool Mercury."

About This Booklet

It was Wednesday 29th March, 1905 that Evan Roberts began his only

mission outside of Wales, in the city of Liverpool, where scores of

thousands of Welsh people lived. He laboured there almost three weeks>

and it is estimated that 750 converts joined the churches as a result of his

ministry. Each evening of the campaign Gwylim Hughes hurriedly wrote

a short sketch of his observations of the meetings and telegraphed them

to the South Wales Daily News, 170 miles away. This book is comprised

of these eighteen vibrant and first-hand sketches.

Preface

THE extraordinary, not to say the marvellous, incidents that marked the

visit of Mr. Evan Roberts, the central figure of the great Welsh Revival of

1904-5, to the city of Liverpool, and the widespread interest they aroused,

call for a permanent record; and the request has reached me from many

quarters for a reproduction in book form of the sketches which, during

those never-to-be-forgotten three weeks, it was my duty to telegraph each

evening to the South Wales Daily News. I am indebted to Messrs. D.

Duncan and Sons, the proprietors of that newspaper, for their kind

permission to comply with this request, and the enterprise of Mr. E. W.

Evans has made possible the reproduction of the sketches in the form

they now assume.

For these sketches no literary merit is claimed. Slip by slip the copy had

to be written hurriedly each evening in the heat and excitement of

crowded gatherings and handed to telegraph messengers in waiting, for

transmission over the wires. Thus, often, the first, half of each evening's

message would be set up in type in the printing office 170 miles away ere

the second half was completed. For this reason the sketches undoubtedly

lack in literary polish; but for the same reason, they have, I venture to

believe, the compensating quality of conveying to the reader the vivid

impressions produced by the many incidents at the very moment of their

happening.

The Liverpool meetings will be memorable for the new phase therein

revealed of Mr. Evan Roberts' wonderful powers.

It was in November, 1904, that after a short term of six weeks at the

Newcastle Emlyn Grammar School, he suddenly returned home to

Loughor, and there, in his native village on the Glamorgan border,

kindled the first spark of the revival which, by the end of February, had

set the whole of Glamorgan, Monmouthshire, and East Carmarthenshire

ablaze and added 80,000 converts to the churches. Then, suddenly at

Neath he withdrew into silence and solitude. For seven days and seven

nights he kept to his room "commanded of the Spirit" to remain mute,

and commune only with God. Emerging from that retirement, he

divested himself of all worldly possessions, sharing his savings

(amounting to £350), among a number of churches, and travelled to

Liverpool in literal obedience to the Divine command - "Take nothing

for your journey, neither staves, nor scrip, neither bread, neither money."

In Liverpool, we saw the missioner turn prophet. We heard his

predictions and marvelled as we witnessed their fulfilment. We listened

- often in pain - to his denunciations of the secret thoughts of men

around him; but, looking back, I cannot recall a single condemnation of

the kind that was not afterwards fully justified. Theologians and

psychologists may explain these things; my province is that of the

historian.

As to the beneficial effects of the mission, let it suffice that during the

three weeks 750 converts were added to the churches; that professed

Christians enjoyed a real deepening of the spiritual life; and that numbers

untold have been compelled to turn serious thoughts to the great issue of

"the life beyond."

GWILYM HUGHES

Cardiff, April, 1905.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

By Sir Edward Russell,

Editor of the Liverpool Daily Post and Mercury.

Mr. Evan Roberts and the Mission.

"The Silent Evangelist" has held his last Liverpool meeting. During the

stay of Evan Roberts, while attention has been largely attracted, few have

known what to say. Many have not known what to think. But from first

to last the phenomena have been unique, and, in presence of them he has

received, not only from all communions, but from the general public,

demonstrations of respect and interest. There has been no indifference.

There has been astonishingly little scepticism. Any scepticism there has

been has scarcely been expressed. The general sentiment has been that

there could be no doubt of the need to which Evan Roberts's

ministrations have been addressed; that the success of those ministrations

showed that he could make the need felt; and that, as good must result -

God speed to it. No one who has encountered this young man has

doubted his good faith. No one could doubt his power over people of his

nation. Nor has anyone disputed the reality of those traits which his

admirers celebrate: his intense and searching gaze, his ready and

illustrative action, his curiously bewitching smile, his devout and

strenuous silences, his appearance of being amenable to instantaneous

impulses, which he takes to be Divine. In this respect it has been rather

shrewdly suggested by a thoughtful member of the Society of Friends

that what has happened with Evan Roberts is only what happens at every

Quakers' meeting. Nor need more be made of it, though there were one

or two incidents which favoured a more fanatical or more supernatural

theory. The idea of good thoughts being put into the mind by God is one

of the first to be entertained, one of the last to be surrendered. He who

can with most conviction and effect convey such communications to

others is the best George Fox or Evan Roberts. In each of these cases the

thing specially notable - the distinctively new trait in evangelism is the

silence, which much overbalances the speech. The trait which has been

least mentioned as to Evan Roberts, but which has been most new, has

been the entire absence of personal push.

If anyone had gone into the great Welsh Calvinistic Church in the Princes

Road, on Saturday evening, without any previous information, he might

well have failed to discover - at all events, till after four hours, and then

he might have been forgiven for missing it - that the 2,500 denselypacked,

visibly excited people assembled had come to hear, and were

longing to bear, a young man who in the main sat saying nothing, doing

nothing, with his head on his hands. He might have been the Rev. John

Williams's unimportant subordinate, waiting to take a message or to start

a hymn. Those who have seen other revivals must know how totally

different this is; and the evidence seems sufficient that from the beginning

of his career in Wales Evan Roberts has behaved in the same way.

Leaving unoffered the transcendental explanation which his disciples in

solemn confidence advance, we may suggest as a rationalistic explanation

the character and ways of the Welsh. There may have been in camp

meetings in America scenes comparable to that of Saturday night. There

have been no such scenes among the English. Go back to Wesley and

Whitefield; come down to Moody and Sankey; if you will, to Torrey and

Alexander; in all the revivals of these there was the visible personal

domination, and in the last two contrived music. Whereas in the Welsh

revival all is voluntary, impulsive. This one starts praying, that one starts

singing, over the whole area of the congregation. The responses to what

is heard are numerous. Response pervades. But no one obtains

monopoly as mouthpiece. As often as not the weird, rhythmic, oftrepeated

cadence of the Welsh petition, frequently in lovely female voices

mellowing from moment to moment under the influence of spiritual

passion, is the expression of some personal agony or ecstasy; desolation

because of some dear one's insensibility to the Divine love or the Divine

authority; joy at the remembrance and the experiences of salvation; tragic

horror at the thought of hundreds then and there on the road to spiritual

ruin; giant-joy in the faith that they will yet be saved.

Ever anon comes by swift casual force of humble personal initiative,

bursting amidst and overwhelming the exclamations and pleadings, the

great, inimitable volume of Welsh hymnody - a vast, solemn, deliberate

torrent of majestic melody. This, the warp of the magnificent soundfabric.

Shooting across it a grand woof of many harmonies, strong,

vigorous, pealing, startling, with all the effect - nay, more than the effect

- of the noblest counterpoint; greater in effect because the singers, the

whole assembly - all knowing the words - are to the manner born of

this matchless musical achievement. A venerable Welsh friend whispers

as you murmur your almost unspeakable admiration, "Because it comes

from the heart." But even then you know that it comes from the heart of

a national being and essence, which has no peer in the musical expression

of spiritual emotion - perhaps no peer in popular possession by spiritual

realities. And this knowledge is deepened as you receive from kind,

eager friends suggestions of the poetic purport of these wonderful, chiefly

minor-key lyrics of two-thousand-voiced power. One of them is an

impassioned appeal for likeness to Christ. Another pours forth in aeolian

strains the air that breathes from Calvary. Another surveys from

Calvary's height all the glories of the world, and serenely declares their

true place in the scheme of things, and the higher range of truths which

Calvary's deed and doctrine have made part of the continuous experience

of humanity.

When the adhesions of converts begin to be taken the singing take

another tone - that of pure joy. A hymn-verse is repeated and repeated

in triumph, and the genius of the people seems to give newness even to

the seventieth repetition. Of the solos, inspired by the wildest emotions

and often sung with frenzied gesticulations in appeal to the Almighty -

but always well sung - we need not speak. Let us note how Evan

Roberts rises and without posing mounts to the height of the occasion.

He eagerly turns the leaves of the pulpit Bible. He struggles with the evil

principle which he seems to see rampant among the unyielding of his

hearers.

He dissolves into his own smile at the thought of precious Bible passages

and sidelights. Big book on shoulder he transacts, but not theatrically, the

lost sheep reclaimed and so carried by the Good Shepherd. Then comes

stress of gloom, and he buries his head in his hands and arms. Anon

comes the head uplifted, the face suffused with the smile, prompted by

something he or another has said. And a curious Welsh peculiarity is that

what is a smile in Evan Roberts is often a quick genial laugh in some of

his hearers. And when you seek the humorous cause, it was no humour,

but a glad recognition of a familiar, household-word, spiritual joy.

Meanwhile, you are one of a vast assembly which for three or four hours

has been, as far as you can judge, intensely and individually racked by

anxiety for the salvation of the unsaved minority present. We are using

the language which best expresses the ideas of the rapt participators in

the scene. It is a great illustration of the strength of the personal

redemption idea in the popular religion of this country that where it is

realised it can produce such a scene, and though the Welsh temperament

is necessary for enacting it, English sympathy has no difficulty in

understanding it. This is true not only in England and Scotland, but in

America and in the colonies - wherever English is spoken. May we

venture to suggest that here comes in the permanent moral of the Evan

Roberts Revival period?

Are our clergy in their regular ministrations justified in laying aside or

leaving to occasional revivalists, as they undoubtedly have done for

years, the active prosecution of the doctrine and practice of conversion?

Whenever British religion has been earnest and zealous this element has

been its key. Because it is in the background in the beautiful quietism of

Keble, the sacerdotalism of Pusey, the reasoned continuity of Newman's

Catholicism, the Oxford Movement has, after all, been a penchant rather

than a popular power. There is, of course, much converting grace in High

Church teaching, and Conversion was long the main business of the

Evangelicals, who had to import it into Anglican usage and phraseology

in order to do under Church of England forms their work in the world.

But of late years the direct insistence on the New Birth has gone much

into desuetude. Yet, if there is one irrefragable human fact, denied by

none of any faith, it is that it must be right and saving (in every sense) to

turn with full purpose of heart to good and to God. The extent to which

this must be connected, either in rationale or method, with this or that

dogma, must be decided by this and that Church. The important thing

for the world is that all Churches alike should insist on the one central

necessity on which Evan Roberts has been insisting, and for which, under

his mystical stimulus, thousands personally and many thousands

vicariously have during the past few weeks in Liverpool been wrestling

with angels. Perhaps the most pathetic incident of Saturday evening was

when it was pleaded for a young man in the galleries that in infinite

distress he was willing and wishful to "decide," but that on Monday he

would have to go to work among his companions, and he felt that then he

might fall. Weak and foolish? Yes; but it is to strengthen such honest

Fainthearts and triumphantly to extirpate by grace such cowardly folly of

unaided human nature that the Gospel ought to be preached, and

effectually, every Sunday. Such is the accruing lesson of the Evan Roberts

Liverpool mission.

One other thing must in honesty be said. Things that exist cannot be

annihilated either by ignoring them or by denouncing them. Let it be

quite understood that the real results of sound inquiry as to Revelation

are not got rid of either because Dr. Torrey protests against them, or

because Evan Roberts says nothing about them. It was distinctly no

business of Dr. Torrey as an Evangelist to make futile protests against the

results of scholarship and reason. It was no business of Evan Roberts to

deal with any such matter: He showed good sense, good taste, and a

sound spirit in adhering to what was his business. The important body of

ministers by whom the Welsh Churches are served are more and more

cultured. The juniors are taking B. D. degrees at the new Welsh

University. For these degrees they are examined by some of the finest of

Biblical scholars. The testimony of those who know is that the members

of Welsh congregations love the old unction, for which they have a

special and untranslatable word, quite as well as ever, but they exact also

weight and thought. It is natural and right that the pivot fact of the New

Birth not only should be continually urged, but may at times collect

around it an accumulated force of special interest and attention. But the

ministers will lead the people into blindness if, either in their teaching or

tacitly, they allow it to be thought that the truths of conversion are

incompatible with the truths of the intellect. Happily there is not even

incongruity between them. We should deprecate in the Revival

atmosphere even an unconscious laying aside of intelligent conclusions.

The New Birth not only does not render unnecessary - it demands -

intellectual sustenance of the New Life.

Sketch 1

The Inaugural Meeting at Princes Road,

LIVERPOOL, Wednesday, March 29, 1905.

Mr. Evan Roberts, this evening, commenced his work in Liverpool, and

for the next fortnight or three weeks, so it is now arranged, he will

minister among the scores of thousands of Welsh people who are residing

in and around this great city. We of South Wales are well aware how

heavily the Liverpool visit has, during the last month, weighed on the

missioner's mind. It was one of the reasons given by him for his

retirement into the seven days' silence and solitude at Neath, but he left

his home at Loughor yesterday fully persuaded that his efforts here

would secure the Divine blessing. Among the Welsh churches of the city

and suburbs, embracing all denominations, the visit has been anticipated

with feverish anxiety, and recent events, with the delays and

uncertainties they involved, have served only to heighten the fever. The

Liverpool Welsh Free Churches Council, the body that has charge of the

mission arrangements, organised in preparation for it a thorough canvass

of the Welsh people of Liverpool. These, it was found, numbered 30,000,

and of these 4,000 are described as non-adherents - that is to say,

persons who do not attend any place of worship. During the next few

days' special efforts will be made to bring these within the influence of

the revival.

Tonight's opening meeting was at Princes Road C. M. Chapel, a

handsome edifice often described as the cathedral of Welsh

Nonconformity. It stands on the Princes-road Boulevard - a magnificent

avenue leading to Sefton Park, and within easy access of the centre of the

city. Simultaneously another meeting was held at the Mount Zion

Wesleyan Chapel, close by, and this was likewise crowded out. That Mr.

Roberts would appear at one or other of these meetings was generally

known, but, outside the committee, no one knew which of the two places

he would select. At six, the chapel doors were thrown open, and for the

next twenty minutes a force of Liverpool police - all Welsh-men - had

as much as they could do to control and marshal the great and excited

crowd besieging the entrances. Under normal conditions Princes-road

Church is assured to seat 1,800 people. This evening it was packed in

every corner, though the aisles were kept free. The stewards had strict

orders to prevent anybody standing in the aisles, and the injunctions

were rigidly observed. Among the occupants of the deacons' pew I

observed practically all the best-known leaders of Welsh Nonconformity

in the city. The Rev. John Williams, the pastor of the church, one of the

great preachers of Wales, was conspicuous, and so also were Dr. Owen

Evans, ex-president of the Congregational Union of Wales, Revs. D.

Adams (C.), W. M. Jones (C. M.) David Jones, W. O. Evans (W.), O. R.

Owen (C.), J. Lewis Williams (C.), Owen Owens (C. M.), J. D. Evans (C.

M.), W. Owen (C. M.) Robert Lewis (W.), J. Hughes, BA., B. D. (C.M.), Mr.

W. Evans, chairman of the Liverpool Welsh Free Churches Council,

Councillor Henry Jones (secretary), and others.

An hour ago, as I wended my way to this meeting, my companion, one of

the best known laymen of the Welsh Calvinistic Methodists, incidentally

remarked, "This is a great and risky experiment, to transplant the

revivalist from his native Glamorgan." It was with some such doubts

also that I scanned this great gathering. Before the missioner arrived, the

atmosphere seemed to entirely lack that spiritual electricity we have been

accustomed to associate with revival gatherings in the Southern province.

Indeed, for the first half-hour the congregation seemed too eminently

respectable to do anything of its own initiative, and assumed an air of

expectancy and curiosity that was chilling, if not absolutely fatal to

anything approaching enthusiasm and spontaneity.

The opening prayer was offered by the Rev. J. Lewis Williams (C.), who it

was interesting to learn is the successor at the Great Mersey Street Church

of the Rev. Peter Price, now of Dowlais, the writer of the recent attack

upon the missioner and his methods. He was followed by the Rev. W. O.

Evans (Wesleyan), and subsequently, after some urging from the "set

fawr," a few prayers were offered in the congregation, and a number of

hymns were sung. The revival "fire," however, had not yet been kindled.

Promptly at 7 o'clock Mr. Evan Roberts entered the pulpit from the vestry

behind, looking in excellent health. With him were Miss Annie Davies

and his sister, Miss Mary Roberts. They were followed by the Rev. D. M.

Phillips, of Tylorstown. Their advent seemed to arouse no special

interest. Evidently, the stolid, phlegmatic Northman is not so easily

excited as his mercurial brother in the South.

Is the revivalist disappointed? This meeting, after his recent experiences,

must seem to him something like an approach to the Arctic regions. He

sits in one of the pulpit chairs, and for the next hour and a half utters not

a word.

Meanwhile let us glance at the audience. Gradually we become conscious

of an increase of fervour in the hymns. The prayers too, seem attuned to

a more spiritual key. We hear the same hymns that we sing in the South,

but - with a difference. They are all here sung in the minor key, and the

tempo is slow and at times almost dragging? Those who pray are of all

ages, old and young. At last, here are two on their feet simultaneously,

both praying loud and long, and ere they finish someone strikes up a

well-known hymn. Presently, the whole congregation is singing with

something akin to enthusiasm.

A minute later Miss Annie Davies is rendering her first revival solo in

Liverpool. It is "I need Thee every hour," and we note with delight that

her voice is so far recovered that today it is as pure as it was in the early

days of the revival, and shows no signs of wearing. Her example inspires

many other sisters to participate in the service, and the prayers that

follow in rapid succession from half a dozen young women in various

parts of the building are stirring and truly eloquent.

It was 8.30 when the missioner first broke silence, and then it was in

terms of severe reproof. Someone had started the quaint Welsh hymn "Y

Gwr wrth ffynon Jacob," the congregation taking it up to all appearance

with great heartiness. But when the fifth line was reached, in which a

desire is expressed for closer contact with God, the missioner, who had

for some half-hour been burying his face in his hands, suddenly sprang

up and, with right arm uplifted and features tear-stained, peremptorily

called upon the congregation to stop. There was instant obedience. "You

ask for closer contact with God," he exclaimed in severe tones, "when

there are in this very meeting hundreds of obstacles to the coming of the

Spirit. There are scores, nay, hundreds here who during the last hour

have disobeyed the Spirit. The lesson of prompt obedience to the Holy

Spirit must be learnt at all costs. He must be obeyed at all times, in all

places, and in all circumstances, in small things as well as in great."

With this introduction the missioner proceeded to dwell upon the~

danger of offending God. "In that never-to-be-forgotten Cwmavon

meeting," he remarked, "some of us saw what it meant to displease God."

Christ had died for a whole world. He was entitled to receive a whole

world in return. Was He to receive it? The sacrifice on the Cross called

for sacrifice on the part of all Christ's followers. Then had been no

successful gathering yet which had not cost something to somebody.

Heaven had cost much. Those who would serve Christ must serve Him

at the cost of sacrifice. They must in the first place give Him their hearts.

With dramatic suddenness the missioner now cut off his address with the

remark, "I can proceed no further. There is someone here ready to

speak." And after a second's pause a lady in the nave speaking in low,

tremulous tones, recited portions of Scripture. Meanwhile Mr. Evan

Roberts, glancing rapidly and excitedly around the congregation, cried

out, "Come, oh! come at once; don't delay." And those near him

observed with some alarm that he compressed his lips, as in a violent

effort to suppress his emotions, that the veins in his temples and his neck

became prominent, standing out like whipcord, and that he bent in the

attitude of a man in a paroxysm of pain. He resumed his seat, and

presently recovered his composure.

There was no call made for "confessions" or "testimonies," and yet for the

next five minutes confessions came from all parts of the building, and this

phase of the proceedings was appropriately closed by Miss Mary Roberts

reading the 4th chapter of the first Epistle General of John. Then, as if

moved by a common impulse, the congregation rang out in a thrilling

rendering of a rousing Welsh hymn, and we felt that at last the

congregation had been thawed, and was under the indefinable spell of

the revival. Hitherto every word uttered in public had been in Welsh, but

someone sang a strain of the revival melody "Come to Jesus," and

English people present, recognizing their own language, summoned

courage to participate in the proceedings. From this point to the end

English prayers, and English hymns were frequently heard.

Still the missioner was not satisfied. Another hour had passed when he

spoke again, and again it was a complaint that he uttered. Either the

Holy Spirit worked differently in the North, or there was disobedience in

the meeting, so we heard declared; but, continued the missioner, the Holy

Spirit was the same North and South. The Spirit was at His best at that

meeting, but hundreds within the building were in deed, if not in words,

saying Him nay. The result of this disobedience was, that he (the

speaker) was not permitted even to give out a hymn, much less to test the

meeting.

Later there was a visible improvement, for the revival feeling rose to a

great height, though in no way approaching anything witnessed in

Glamorgan. At ten o'clock the meeting was tested by the Rev, John

Williams, and a dozen converts were enrolled. The revivalist's closing

words were a solemn warning to unbelievers.

It must he recorded that at this inaugural meeting the revivalist fell far

short of doing justice to the reputation that had preceded him, and

possibly many left the building disappointed. It is yet too soon, however,

to form any conclusions. Mr. Evan Roberts is evidently feeling his way,

and those who know him best are confident that in a few days the

extraordinary outburst of religious fervour which marked his visits to the

towns of Wales will be witnessed also in this great seaport on the Mersey.

As we left the crowded building, we had outside to fight our way into the

streets. Through a great throng inside the chapel railings, who all

through the evening had been holding a revival service of their own in

the open air. In this service dozens of Welsh policemen of Liverpool,

drafted thereto by the chief constable, took conspicuous part.

Sketch II

At Anfield. - A Chant of Praise. - Features of the Mission.

LIVERPOOL, Thursday, March 30, 1905.

Disappointing as was last night's meeting at Princes Road Chapel to those

familiar with revival scenes in South Wales, the Liverpool people express

themselves delighted with it. They regard it as an unqualified success.

"Mr. Evan Roberts made an excellent first impression" is the phrase we

hear on all sides, and this view is amply confirmed by the Liverpool and

Manchester morning papers, all of which find in the Princes Road

gathering ample justification of the renown which the revivalist has won.

"We did not anticipate," said a leading local minister to me today,

"witnessing in Liverpool anything like the stirring scenes you have had

down South. I question whether our people here are capable of any

extraordinary ebullition of feeling, and we do not desire it; but there

prevailed at last night's meeting a deep and intense feeling which was

unmistakable, and the revival, we feel confident, is taking a firm hold of

the city."

In a conversation with the Rev. John Williams, of Princes Road, today, I

was told something of the manner in which the city had been prepared

for the coming of the mission. A house-to-house canvass of so vast a

community as Liverpool is surely a task that would not be lightly

undertaken by any body or association, no matter how highly organised,

but the Welsh Free Churches of Liverpool, having conceived the idea, did

not rest until it was carried into execution. The work was divided

between the churches, and for many days one thousand canvassers were

daily at work. Not a house was left unvisited, either in Liverpool or the

suburbs, including Birkenhead and Garston, and at each the inquiry was

made, "Are there any Welsh people here who do not frequent places of

worship?" In the result, as previously stated, 4,000 such prodigals were

discovered.

While this work was in progress, the canvassers met every Sunday night

for prayer, and at one of these meetings someone conceived the happy

idea of organizing during the mission special gatherings for this class of

non-church goers. I hear today that three such meetings have been

arranged in three different parts of the city, and they will be held next

week. These meetings, every one of which Mr. Evan Roberts is anxious to

address, are expected to be the feature of next week's programme.

Mr. Evan Roberts, I ascertained this morning, is in the best of health and

spirits, and is deeply grateful to the Liverpool committee for the very

excellent arrangements made for his comfort. The address of the house

(No. 1 Duc's Street, Princes Park, the residence of Mrs. Edwards) in which

he resides during his stay in the city is kept a profound secret, and he is

thus enabled to enjoy rest and freedom, and to escape the unweleome

attentions of the army of inquisitive callers who had been dogging his

footsteps in other places. I very much fear, however, that the secret will

soon become public property, for as I passed the house this morning I

observed a crowd of the curious ones in the immediate vicinity watching

the carriage which had just arrived to take the revivalist out for his

morning drive.

Tonight's meeting is held in the northern end of the city, the chapel

selected for the missioner's visit being that of Anfield Road, opposite

Stanley Park. Simultaneously three similar gatherings, all crowded, were

held in other chapels in the vicinity. Commodious as is the chapel at

Anfield Road, for it will comfortably accommodate 1,200 people, it

proved hopelessly inadequate to house the enormous crowd that

besieged all the entrances at 6 o'clock. Three minutes later every inch of

room within was occupied. Then the doors were finally closed, and the

pastor (the Rev. Owen Owens) conveyed to those within, a message from

the chief constable of Liverpool that no one was to leave the building

until the close of the proceedings. This precaution, it was explained, was

necessary so as to avoid crushing and panic.

It was an inspiring audience, typically Welsh, with a slight sprinkling

perhaps of other nationalities. The spirit, of idle curiosity so painfully

evident at Princes Road was tonight markedly absent; and ten minutes

after the congregation was admitted I could detect nothing to distinguish

the meeting from the finest revival gathering seen even in the Rhondda

and the Garw. The Rev. Dr. Abel T. Parry, D.D., of Rhyl, an ex-president

of the Welsh Baptist Union, had scarcely finished reading the

introductory chapter ere a lady under the gallery was heard in earnest

supplication. She was immediately followed by two young men, one a

mere boy, and both prayed with irresistible power. Their theme was one

of praise that in this revival the young men of Liverpool had been deeply

immersed in the baptism of the Spirit. This elicited loud and fervent

"Amens" from all parts of the building, and presently the "gorfoledd"

found adequate vent in hymn after hymn. During the brief intervals

between the stanzas we heard the music being repeated by a choir of

apparently many thousand voices clustered in the streets on three sides of

the building.

Let us glance around. While the congregation is yet singing, fully half a

dozen persons in as many pews up and down the building are engaged in

prayer, and as the music ceases we hear their voices, pitched in a quaint

and musical monotone, betraying their North Wales origin. All of them

are apparently blissfully unconscious of their surroundings. Like Jacob,

one is wrestling for the blessing;, another, striking an altruistic note,

pleads for the baptism of the Spirit upon all and sundry, but especially

upon Evan Roberts, "Thine honoured servant.".

No one is in charge. The conduct of the meeting is entirely in the hands

of the congregation. The spontaneity of the proceedings is delightful.

Prayers and hymns follow absolutely without interval, and, as in South

Wales, we occasionally have a dozen people simultaneously on their feet.

Last night Mr. Evan Roberts - he has I see, just arrived, he is now in the

pulpit, though his arrival has created no commotion - the revivalist, was

taken aback by the lack of warmth at the Princes Road service, and asked

whether the Spirit worked differently in the North from the way He

worked in the South. Surely such a query would tonight be quite out of

place. The ladies are now very much in evidence, and striking and

beautiful are some of the prayers they offer. "The Pentecost that was lost

through unbelief must come again," exclaims one, while the next pleads

that the Lord should make them "all Marys, all prostrate at the feet of

Jesus."

Shortly all eyes are fixed on the pulpit. Miss Annie Davies is singing the

revival love song,

"Dyma gariad fel y moroedd,

Tosturiaethau fel y lli'!

T'wysog 'bywyd pur yn marw,

Marw i brynu'n bywyd ni!

Pwy all beidio coflo am dano?

Pwy all beidio traethu'i glod?

Dyma gariad nad a'n anghof -

Tra bo'r nefoedd wen yn bod!

In a second or two she is complete mistress of the congregation. All seen

enraptured by the vocalist, who, despite her glorious voice, evidently

thinks more of her theme than of her art. She sings as one inspired. The

line "Dyma gariad nad a'n anghof" ("Love that cannot be forgotten") is

rung out again and again at the top of her voice with telling effect, and,

presently, in contemplation of His love thus extolled, hundreds are

silently weeping. A Wesleyan Methodist minister from Paris offers

prayer in English for France; Gipsy Smith's brother-in-law, Mr. Evens,

offers another for the salvation of the world, and other Englishmen and

Englishwomen follow their example.

Why this silence of the missioner? It is nine o'clock; two hours have

elapsed since he took his seat in the pulpit, but he has not yet uttered a

word, nor has his face been once lit with a smile. Half an hour ago he

bent his head and hid his face in his hands; now, as the congregation are

absorbed in a rousing rendering of the Welsh Christian war march,

"Marchog lesu yn Ilwyddianus," 'he seems to be rousing himself from a

reverie and to be taking an intelligent interest in what passes around.

A young fellow in the gallery has been praying for a downpour of the

Spirit. It was this that brought Mr. Evan Roberts at last to his feet. "No,"

he exclaimed, "don't ask the Spirit for the downpour, for we shall not get

it. The Spirit will not come in all His fullness until a place is prepared for

Him." Hence, he continued, the need for whole-hearted dedication of self

- body and soul - to the service of God. Some prayed for a revival, and

yet closed the doors of their own hearts against it; others were ready to

do great things for God, but refused to do the lesser things for Him. They

must learn to do the lesser things before they would be permitted to do

the greater things. Was that meeting a success? Yes, perfectly; but Jesus

had not been given all the glory that it had been possible to give Him, nor

yet as much glory as He desired to have. They must not rob God of His

glory. They must make up their minds to give all for God or all for the

Devil. Each one of them must attract people to Jesus or repel people from

Jesus. Which was it to be? In many Christian hearts Jesus reigned, while

the will, the affection, the intellect, had not all been subjected to Him.

There was need to rub the rust off many a follower of Christ. God needed

workers, not men. Jesus was the greatest worker the world had ever

seen, and he who would be like the Master must be ready to be bent, and

to be humiliated, even as the Master was.

For fully five minutes after the revivalist had suddenly ceased speaking,

there is a silence that can be felt. Evan Roberts, bending over the pulpit

desk, glances up and down the silent, solemn congregation with face now

smiling, now sad, his solitary remark being,

"I have stopped, because I feel that now in this chapel scores are

weighing themselves in the balance." Eventually the painful silence is

broken by a touching prayer from the gallery for Universal peace,

universal salvation." "Thou hast saved the Welsh, O Lord," ran one of

the phrases, "save also the English, and the Scotch, and the Irish," and the

congregation after a loud "Amen" breaks forth into a fervent and ecstatic

rendering of "Diolch Iddo."

A little later the delicate task of testing the audience is conducted by the

Rev. Owen Owens. On this occasion church members are asked not only

to stand up, but to raise the right arm, and at once we see a whole forest

of arms uplifted. "Up with them," cries the missioner, "up even unto

Heaven if necessary; remember the arms that were once extended on the

Cross." Are there any arms down? Only a few. Two, three, four

converts are announced in rapid succession, and after each

announcement the revivalist, who is now as eager and boyish in manner

as he was wont to be at the beginning of this historic movement, leads the

audience in a great chant of praise.

"Here is one who doesn't want to give in," The voice comes somewhere

from the far end. "He won't? " asks the revivalist, "Let him beware lest

the cry soon be that he shall not." Another man was said to decline

because "he knew too many of the tricks of some who were church

members." "It will be every man for himself in the great day to come,"

was the revivalist's response, "Do you find any fault with God?"

It was close upon 11 o'clock when the meeting terminated, and a similar

gathering held in the adjoining hall was simultaneously brought to a

close. These Anfield meetings, if I mistake not, mark the beginning in

Liverpool of a movement destined to prove as marvellous as that

witnessed even in South Wales.

Sketch III

The Duty of Forgiveness. - Sensational Scene at Birkenhead.

BIRKENHEAD, Friday, March 31, 1905.

Throughout all the great centres of population skirting the banks of the

Mersey, Evan Roberts, the Welsh revivalist, is undeniably the hero of the

hour. His name is on every lip, his pictures are exhibited in hundreds of

shop windows, and repeatedly today have I heard the regret expressed

that the mission is not conducted in the universal language of the Saxon,

and held in the Torrey-Alexander pavilion, which is still up, and in which

14,000 people could be accommodated. Evan Roberts has, however, come

to Liverpool to conduct a mission to the Welsh people in the language

they know best, and, as to the second point, the Welsh revivalist has not

yet, except in one solitary instance at Bridgend, conducted a service since

the beginning of the revival in any building not habitually used as a place

of public worship. The Liverpool Committee, in arranging a series of

suburban gatherings in preference to any central demonstration, are not

only carrying out the wishes of the revivalist himself, but are keeping the

movement in Liverpool and district strictly on the lines that have led to

success in the towns and valleys of Wales.

The scene of operations today was changed from Liverpool to

Birkenhead, and we are assembled this evening in the spacious chapel of

the English Primitive Methodists in Grange Road. It is yet but six o'clock.

The revivalist is not due for another hour, but the building was packed,

and all the doors closed half an hour ago. Since then thousands have

been turned away. Two other chapels in the vicinity, we are informed,

are also crowded out. They are the English Baptist Chapel, Grange Road,

and the Welsh Wesleyan Chapel, Claughton Road. In which of these

three chapels will the revivalist appear? Anyone knowing the secret, and

willing to part with it for a consideration, could have added considerably

to his wealth during the last few hours. But the committee have kept

their secret well, and there are not many, even in this congregation, who

know that this is the chapel which the missioner will favour.

Looking around I recognise in the solitary occupant of the pulpit pew the

form and features of the Rev. Thomas Gray, of Birkenhead, who must

now be numbered among the veterans of the Welsh Calvinistic Methodist

ministry. He is "in charge" pending the missioner's arrival, but the

congregation is already aflame with the spirit of the revival, and any

attempt at leading would be out of place. An eloquent prayer for "the

lessening of immorality and ungodliness in the town" is offered by the

Rev. William Watson, the well-known Presbyterian minister of

Claughton, but this is the only English we hear during the first hour,

though there must be a large number of Englishmen present. The next

prayer is in Welsh, and he who offers it, a middle-aged man of the artisan

class, is evidently a recent convert. In the fluent, vigorous phrases that

fall from him, we glean a bit of his personal history. For 20 years he had

been a pronounced infidel, but two months ago the light came, darkness

and doubt were for ever-dispelled and faith and conviction had been

enthroned. It is a great prayer of thanksgiving, and the congregation is

deeply stirred. The joy of the last two months is poetically depicted, but

we are told that the only true happiness is that derived from bringing

other souls within reach of the mercy of God. We must all be fishers of

men and winners of souls. The same altruistic note is struck in many

other prayers.

The Mission of the Welsh, it has often been written, is to counteract

materialism, and to deepen the spirituality of the human race. If this be

so, then the revival helps the nation to fulfil its destiny. A writer in a

Liverpool daily today claims to have found the secret of the revival. It is,

he asserts, the power of the Welsh people to sing. Had he made the

remark after hearing this Birkenhead congregation tonight, one might be

tempted to pardon him. In all my experience of the revival I have

certainly heard no more inspiring singing than this. Perhaps the

explanation lies in the fact that there is here a large number of visitors

from Festiniog and other North Wales centres, though I am reminded, by

the way, that the Welsh vocalists of Birkenhead have on more than one

occasion asserted their superiority in the chief choral and the ladies'

choral competitions of the National Eisteddfod. In the prayers, as in the

hymns, there is in every word an unmistakable heart-throb, and

occasionally the building re-echoes to the sound of loudIy-proclaimed

"Amenau."

It was a few minutes past seven when the missioner arrived. He at once

took his seat, with the Rev. John Williams, in the pulpit. Miss Annie

Davies was accommodated with a seat in the front. For some reason the

missioner's sister is tonight absent. The arrival of the missioner causes

an unusual flutter of excitement, and his features are closely scanned, and

his every movement eagerly followed by an excited throng - but only

for a moment. A fervent prayer is heard in the galleries 'that we may

look to Thee, oh Lord, and not to Thy servant," and thus recalled to the

spiritual aspect of the gathering, the congregation abandons itself once

more to an ecstasy of praise. In a subdued voice Miss Annie Davies gives

an exquisite rendering of Sankey's 'I hear Thy tender voice," and a

solemn hush falls upon the assembly as it drinks in every warbling note

that trills from the throat of the youthful singer.

In the audience are scores of young men and women from Rhos, aflame

with the fire of the revival, kindled there simultaneously with the

outbreak at Loughor. They are easily distinguishable by the fervency of

their prayers, and presently four or five of them are heard addressing the

Throne of Grace in voices pitched in a high, tremulous key, pulsating

with emotion.

We begin to feel that this is going to be an unusual service, for the

atmosphere is surcharged with that indefinable something so frequently

experienced, at Evan Roberts's meetings. Call it hypnotism, magnetism,

or what you will, or apply to it the revivalist's own description, "the

Operation of the Holy Spirit," the effect is unmistakably manifest. Hearts

beat quick and faces grow pale. There is a catch in the throat, and a deep

consciousness that something is about to happen. A silence supervenes

that is positively painful - the tension is at breaking point.

Half a dozen voices start a hymn, the congregation makes an effort to

follow, and anon the, revivalist, rising suddenly from his seat, excitedly

seizes the pulpit Bible and quickly turns o'er its leaves, as if in search of a

text that is eluding him. Then, surveying the congregation, with face

twitching as if with pain, and eyes full of pathos and sorrow, he sternly

demands "silence, stop!"

The congregation is startled, and looks up. The hymn is abruptly stopped

in the middle of a line. "Stop," repeats the missioner. "Stop, we must

first clear this place before we can sing. A moment ago a friend over

there beseeched God to come nearer, but He will not come nearer until

some things here are cleared out of the way."

What is amiss? Each man looks with wonder at his neighbour, and we

seem to read in the astonished faces that are turned towards the pulpit

the startling question, "And is this man in the confidence of the

Almighty?" Presently, the missioner proceeds to explain. "There are

some here tonight who cannot pray the Lord's prayer, 'forgive us our

trespasses as we forgive those that trespass against us.' Why? Because

they will not forgive those that have trespassed against them, and they

are here tonight, and are obstacles in the way. Think not this is

imagination, say not this is a flight of fancy; it is KNOWLEDGE. They are

here, as certain as I am here, as certain as God is here," and, proceeding,

he urges those thus alluded to, to forgive at once.

The scene that follows baffles description. Frantic prayers are heard from

many parts of' the building. List to some of the phrases, "Bend them, oh

Lord." "Forgive us and strengthen us to forgive." "Pardon our

hypocrisy." "Bend the entire congregation." A little boy of eleven, who

is in the gallery behind the pulpit, offers a prayer that is beautiful and

touching. "Let love prevail like the ocean," he cries, "to enable us all to

forgive and forget trespasses, and to think only of the infinite love of God.

"

Again the congregation, with more than half of its members in tears,

starts a hymn, and again, the missioner imperatively intervenes. "These

people decline to forgive, and some of them are important personages,

too. Let them beware lest the Spirit compels them to stand up and

publicly denounce their own iniquity, nor must they be surprised if their

names are given me. God is revealing Himself in wonderful ways these

days."

This, we know from experience, is no idle threat; and we recall memories

of that extraordinary meeting at Blaenanerch, when the missioner who

now speaks actually pronounced a name under circumstances similar to

these.

Again we hear a multitude of prayers. One of the number is by a young

man, who is described to me as a leading official of the Free Church of the

Welsh (Eglwys Rydd y Cymry), the section that recently seceded from the

Calvinistic Methodist body in Liverpool. I look up and recognise him.

He took a prominent part in the painful historic controversy that

preceded that secession. We seem to be getting a glimmer of light on

what is happening. Are hostile leaders in this meeting, with hearts still

filled with bitterness and rancour? "Unite us, O Lord, unite us" is the

young man's piercing cry, and again he repeats it, and again and again he

is followed by loud "Amens." Sounds of sobbing fall on the ear from all

sides. He who prays proceeds: - "We are in a hopeless tangle. Lord,

reduce us to some semblance of order. We are in mortal fear of quitting

this meeting until we are assured we are all brethren and sisters in Christ.

Bend us all until every church in the district is ready to co-operate for the

furtherance of Thy Kingdom." Is this a reference to the recent decision of

the Welsh Free Church Council of Liverpool not to admit the Free Church

of the Welsh into its ranks? Other rhapsodies in the same prayer are

equally pointed.

After this it seemed the most natural thing in the world to hear prayer

after prayer in which were heard the declarations, "I thank Thee, Lord,

Thou hast given me the strength. I forgive all now. I beseech Thee to

grant me Thy forgiveness." "No," declared the missioner, a little later, "It

is not clear here yet. There are still some here who refuse to forgive.

They are stubbornly resisting the promptings of the Holy Spirit. They

must not expect any sleep tonight. God in His own good time will deal

terribly with each of them. May He have mercy upon them."

The Rev. John Williams, speaking slowly and solemnly, asked the

congregation to unite with him in the Lord's Prayer, and at once 1,800

people bent in supplication, and with faces lifted, offered in Welsh the

Lord's Prayer, repeating with significant emphasis the passage referring

to forgiveness. When the Welsh version is finished Miss Annie Davies

leads the assembly in an equally fervent repetition of the same prayer in

English. Then the revivalist, with face beaming with joy, exclaims, "At

last, the Spirit is permitting us to sing. Let us then sing,

"Ymgrymed pawb i lawr

I enw'r addfwyn Oen!

Yr Enw mwyaf mawr

Erioed a glywyd son:

Y clod, y mawl, y parch, a'r bri

Fo byth i enw',n Harglwydd ni!"

In the rendering of this noble hymn, the missioner himself leads the

congregation, and then the incident is closed by Miss Annie Davies with

an exquisite rendering of "Dyma Feibl Anwyl lesu" wedded to the music

of "The Last Rose of Summer."

"Will those who would like to love Jesus, put their hands up?" The

question is put by the Rev. John Williams, and there is prompt response.

Every arm in the building is uplifted. The revivalist claps his hands with

very joy.

Soon afterwards many converts were enrolled, among the names called

out being that of Mr. - - who, it was explained by the Rev. Thomas

Gray, "is a brother of the Rev. - - a well-known South Wales minister."

"Oh," retorts the missioner, "he has found a better brother in Jesus tonight.

"

It was a long way past ten ere this remarkable service ended. While it

proceeded members of the Y.M.C.A. of Birkenhead conducted an equally

remarkable open-air service outside the chapel, where many thousands

were gathered.

Old Feuds Healed. Saturday.

At the Birkenhead meeting last night the hindrance mentioned by the

revivalist was the presence in the congregation of people who refused to

forgive their enemies. Today I have received full details (including

names, addresses, etc.) of an incident which in this connection will be

read with interest. There were present at the meeting a brother and a

sister, both advanced in years, who for 20 years had not spoken to each

other. Every effort at reconciliation had failed. During the stress of those

never-to-be-forgotten moments, when the revivalist depicted the

sinfulness of hatred and the duty of forgiveness, both agreed to forgive

and forget, and to seek reconciliation. Outside the chapel the two

accidentally met, mutually embraced, craved each other's pardon, and

then walked home together linked arm-in-arm.

Sketch IV

Five Envious Persons. - A Dramatic Accusation. - Service for Non-

Adherents.

LIVERPOOL, Saturday Night, April 1 1905

A special meeting exclusively for non-adherents is surely a novel feature

even in a revival which, from its beginning, has been run on unusual

lines. The idea of organising such a gathering was conceived in

Liverpool, and tonight we witness in Liverpool the first attempt to carry

the idea into practice. On paper the arrangements were perfect.

Hundreds of pink tickets were distributed exclusively, so we were

officially assured, to non-adherents, while canvassers who were

responsible for bringing these "esgeuluswyr" once more within hearing

of the evangel, were supplied with white tickets, securing their own

admittance only on condition that they brought one or more nonadherents

with them. This is the first of three similar ticket meetings to

be held during Mr. Roberts's visit to the city.

Very often, alas, the best laid schemes "gang agley," and tonight's effort,

from all appearance, has not been the success it was hoped for. What

than is lacking? Certainly not enthusiasm. The crowd is greater than

ever. Shaw Street Chapel, in which we are now assembled, is the chapel

of the Welsh Wesleyans, where the late Egiwysbach ministered for some

years, and is possibly one of the most commodious places of worship to

be found in the north end of the city. Now at 6.50, 20 minutes after the

doors were thrown open, it is packed from floor to ceiling.

Looking at the congregation from the pulpit end, what do we see?

Ministers and preachers of all denominations clustered in and about the

pulpit pew; deacons and leading church workers, whom we recognise as

having met at previous gatherings - they are all here with zeal and

vigour undiminished. Scan the pews closely and critically, and note how

they are crowded with well-dressed men and women - typical chapel

goers, every one of them. And if you are in any doubt on that point listen

to the singing! In what church or chapel in all Wales can you hear 'a

heartier, a fuller-throated, a more soulful and "hwyliog" rendering than

this of the music of the sanctuaries of Cymru? There is not a single hymn

book in view on balcony or floor. Close your eyes, and as you hear hymn

and prayer and testimony and confession, you can emphatically declare

that this is a Welsh valley where revivalism is at fever heat. This a

congregation of non-adherents? Have the Mission Committee been

befooled on this first day of April?

When on the point of putting this very question to one of the officials, my

ear caught a few phrases of protest from the Rev. W. 0. Evans (Wesleyan),

Bootle. He is in the set fawr, and facing the audience makes a pointed

appeal - "Outside there are hundreds of non-adherents with tickets, but

they cannot come in. Will those in the audience who are Christian

members quit the building and make room for some of them? "What a

fine opportunity this for the exercise of a little Christian self-denial. But

no; so far as I can see there is scarcely any movement. The appeals fall on

deaf ears, and the next minute we are caught in the mighty sweep of

another Welsh hymn. Turning to the Rev. W. O. Evans I ask, "Are there

any non-adherents here?" and the sorrowful reply is, "There are

hundreds of church members:" "Nay," said a voice behind him, "there

are hundreds of esgeuluswyr, too. We have been bringing them in by the

score all the afternoon, in cabs, in wagonettes, and by trams. Many of us

have been for hours after non-adherents, just as on election days we run

after the voters."

All this of course may be, but what business have these church members

at all in this meeting, arranged for those who are outside the pale of the

Christian churches? How obtained they the tickets? Have non-adherents

been trafficking with the passports supplied them? Outside, as I write,

many hundreds have assembled who have come by a late afternoon train

from Wrexham, Rhos, and other districts in North Wales in their

eagerness to attend one of the Liverpool meetings; but, alas! they are

turned away disappointed.

From six to seven, the meeting is more or less in charge of the pastor of

Shaw Street. the Rev. Robert Lewis, and others in and around the

platform include the Revs. Griffith Ellis, M.A., Bootle (C.M.); W. O. Evans,

Bootle (Wesleyan); Thomas Hughes (Wesleyan); Owen Owens, Anfield

(C.M.); John Hughes, M.A., Fitzclarence Street (C.M.); J. D. Evans. B.A.

(C.M.); David Powell (B.); John Hughes, BA., B.D. Princes Road (C.M.);

Hawen Rees (C); O. L. Roberts ('C.), Tabernacle; D. C. Edwards, M.A.

(C.M.), Llanbedr; Hugh Roberts (C.M.); E. J. Evans (C.M.), Walton;

Thomas Charles Williams, M.A. (C.M.), Menai Bridge.

It is 7. 15. Here comes the missioner. What's this change? Swiftly

mounting the pulpit he stands facing the vast congregation with delight

in every feature. Is this he who last night at that memorable Birkenhead

meeting threatened a terrified congregation with Divine wrath? The

pain, the sorrow, the anguish, the pity, and the anger then reflected in his

countenance are apparently gone - all gone. The Evan Roberts whom

we now see is the smiling, jovial, light-hearted, merry evangelist who in

the early days of the revival spread the gospel of hope and joy through

the mining valleys of South Wales. What has happened?

There is tonight, no suggestion of that mood of reticence and reserve,

which have hitherto marked his appearance in Liverpool. Bending over

the pulpit desk he beams with delight upon the congregation. His face

wreathed in captivating smiles. Some one starts a hymn as he is about to

speak, and someone else cries "Hush." "Nay. nay," replies the

evangelist, "you sing on, sing on," and thus encouraged, we have hymn

after hymn, and prayer after prayer, now in English, now in Welsh and as

often as not half a dozen engaged in public prayer together. Suddenly

Annie Davies's voice rings through the building, and there is instant

silence. In the middle of her solo she is overcome with emotion: the solo

is turned into a sobbing prayer, Turning to the audience, we observe

hundreds in silent tears who a moment ago were jubilant singers. But it

is only a gentle summer shower, and anon the clouds pass away, and all

is sunny again.

A few minutes later the missioner is on his feet with a new-found text. It

was evidently suggested to him by the prayer of the Rev. W. O. Evans,

who in his supplications had asked that their ears be attuned to hear the

voice of Jesus. "This is His voice," declares Evan Roberts, "Come unto

Me all ye that are weary and are heavy laden and I will give you rest" -

On this favourite verse, the young preacher founded a bright, winsome

address, in which it was shown how the needs of the 'fallen race were

more than met by the love of Christ. He alone could relieve us of

burdens. "Come," and the missioner beckons again and again, as if

addressing individuals in the audience. "Come! Come!" What

tenderness, what pathos, what loving-kindness, he throws into this one

word, "Come!" "You have fallen to 'the depths, some of you," he

continues, "but Jesus has not yet given you up. His word is still 'Come.'

When to come? Jesus has no special hour of call. Come early, come every

hour, every minute, every second. You feel too weak? He will give you

strength. Naked? He will clothe you. Steeped in sin? He will cleanse

and purify you and attire you in a royal robe, a robe that shall cover not

filth and iniquity, but purity, and a purity that will whiten the robe."

A Prediction and its Fulfilment.

The speaker is silent. For a moment he surveys the congregation with

love-lit eyes, and then remarks, in a low, soft, musical voice: "When I

came in, this place was full of angels. There is a fierce battle now going

on here. Who is going to win? Jesus Christ." Again he pauses, again we

have silence, and hundreds are in an expectant attitude as if listening for

the flutter of angel wings. "Think not," is the next remark, "that this

great effort of yours in Liverpool is going to fail. No, there is too much

love in it for failure."

A little later he again embarks upon a prophecy. "Are there some who

are to come to Him tonight? Yes. How do I know? Because I have

asked that it shall be so, and because I have the assurance that it shall be

so. Jesus is waiting to relieve your burdens, and scores of you here are

going to yield yourselves up to Him tonight and when the burden is

removed you can then sing in the day and sing in the night (canu'r dydd

a chanu'r nos). There will be then no night, for you will be with Him,

Who is the Light."

Just at this moment, as we marvel at the prophecy, and wonder whether

we shall witness its fulfilment, Miss Annie Davies's voice is heard softly

rendering Sankey's hymn in Welsh, "Os caf lesu, dim ond lesu" ("If I

have Jesus, Jesus only ").

"This is the beginning of glorious times in Liverpool." The speaker is the

Rev. John Williams, of Princes Road, who now stands at the pulpit desk.

With tact and delicacy he proceeds to test the meeting. "All who want to

love Jesus, will they raise their hands?

A second invitation is not needed, every hand is up. "Da lawn." remarks

the reverend gentleman; "but if you really desire to love Him, your place

is inside, not outside the churches."

When those who were already members of churches were asked to stand,

about two-thirds of the congregation sprang to their feet. Ah! I thought

so. Non-adherents are in a hopeless minority. In less than a second the

set fawr is emptied. Ministers and officials who had sat there are now

rapidly threading their way in and out of the crowded congregation in all

parts of the building in search of stricken ones.

The net having been thrown out is drawn in. We now see the prediction

fulfilled. Dozens of repentant sinners are discovered, some prostrate with

grief, others engaged in prayers, and still others too overcome to speak.

Names of converts are called out in apparently endless succession. I keep

record up to 30 and even 40 and then the names come in too rapidly and

in batches, and I am unable to follow. This must rank amongst the most

successful meetings that even this unrivalled revivalist has ever held.

Surely he must be overjoyed. Where is he?

While the congregation are, for the sixtieth time, singing Diolch Iddo,

Byth am goflo llwch y llawr," I try to discover the missioner, who for ten

minutes past has been silent. Ah, there he is at the far end of the pulpit,

his 'face buried in his hands as if weeping. Why this mood, when all is so

bright? We see signs of a coming storm.

Returning to the pulpit, the Rev. John Williams announces "There are

scores here engaged in a bitter struggle. Let us pray for them," and at the

word the Rev. Owen Owens leads the congregation to the throne of grace,

and he is followed by dozens of others in English and Welsh. Meanwhile

a lady in the congregation, with a rich contralto voice, gives a perfervid

rendering of the sacred solo, "There is life for a look," and presently a

thousand voices join exultantly in the refrain.

But we are suddenly pulled up by the missioner. With both arms raised

he sternly demands silence. He is in tears, and his brow is clouded.

What's wrong? "Don't sing." He speaks with a voice that is choked.

"Don't sing. Oh, the tragedy of it. When salvation has been secured by

so many, the Spirit has suddenly departed, and some of you know the

reason." Why? The congregation looks bewildered, failing to detect the

slightest reason for the interruption, and possibly many resent it. A

minister, more courageous than his brethren, calls out, "Here is another

soul crying for rescue. Let us rejoice." "No," replied the missioner, with

increased severity, "Don't sing, Diolch (thanks); there's no Diolch due to

some who are here, though there is praise due to Heaven for all that."

Then with scorn-flashing eyes, clenched fists, and in a heightened voice

he exclaims, "Some of you are jealous, envious (eiddigeddus) because of

the rescue work that has been accomplished, and you who are guilty

must at once ask God to forgive you - yea, to bend you. This, oh this, is

awful. Men jealous because Christ is being glorified! "

A thrill of something akin to horror passed over all present at this

extraordinary pronouncement. In the pulpit, on the gallery, on the

ground floor, everywhere around us, men and women cry out in prayer.

The air is full of the sounds of moaning. The missioner, as he bends with

closed eyes over the pulpit desk groans as if in physical pain. The

moaning gives way to loud, and bitter lamentations. Women shriek, and

many are on the point of fainting. The situation is excruciatingly painful,

almost intolerable. Well-known ministers exchange despairing glances.

"Plyga nhw, O! Dduw" (" Bend them, O Lord") cries the missioner, and

the prayer is repeated by hundreds of others, who are kneeling.

Clear as a bell rises the resonant voice of Mr. William Evans, of Newshani

Drive, one of the deacons of Anfield, and an ex-member of the Liverpool

City Council. "Forbid it, Lord " - this is his supplication - "that there

should be any elder brothers among us tonight." "But there are," swiftly

rejoins the missioner, "and these persons have not yet asked for

forgiveness. They are the obstacles. In the Name of the Lord I ask them

to go out or bend. Let us as one great army again beseech the Lord to

bend them."

And once again the building resounds to the earnest, almost hysterical,

pleadings of hundreds. Presently, the terror increases, when the

missioner, having presumably received a still further revelation, commits

himself to a still more definite statement - "There are five persons here

who are obstacles. Will you five go out or seek forgiveness? We shall not

be allowed to sing or to test the meeting, nor shall we see any mere saved

here until something happens. If this proceeds much longer, perhaps the

names of the five shall be revealed to me."

Wild and Delirious Scenes.

What is to be done? The scenes now witnessed are wild and delirious.

Tension is at breaking point. A happy thought occurs to the Rev. W. O.

Evans, a Wesleyan minister. Perhaps, the five are Englishmen who do not

understand that they are rocks of offence, and, presumably, with a view

to enlighten them, the minister breaks forth into an English prayer for a

relief of the crisis that has arisen. But the missioner forbids him to

proceed.

"They are not English friends," he cries, "they are Welsh, all five of

them." "Save them, Lord," a woman prays. "No, no," excitedly

interrupts the revivalist, "don't pray; God is not listening; Heaven is

locked against us, as it were. Three of the five are preachers of the

Gospel. There is a terrible ordeal in store for the five."

It needs a more graphic pen than mine to depict the sensation produced

by this declaration. "Five men, three of them preachers." This is the

statement, and inferentially it is a statement made under Divine

inspiration. It is received with loud and general exclamation of "Oh, dear

oh, dear!" in tones of mingled pain and astonishment.

The uppermost feeling seems to be one of utter despair, and I experience

an uneasy feeling that unless this acute tension is speedily relieved there

may be a panic. The Rev. John Williams, standing in the pulpit behind

the missioner, who is bent as if in a trance over the desk, appears to share

this disquietude, for, placing one hand firmly on the missioner's

shoulder, he with the other beckons silently to the congregation to depart.

A few take the hint, and frantically endeavour to push their way out. The

great mass remains, anticipating developments. Then Mr. Williams,

resolved to take no more risks, quietly makes a few simple

announcements, and without consulting the missioner pronounces the

benediction and declares the meeting over.

Just at this moment Mr. Evan Roberts stands upright, and realising what

is happening, turns an affrighted glance to the minister and assumes an

attitude of protest. Then appealing to the congregation he cries: "No,

don't go out. Pray! Pray! Pray! We cannot leave until Christ is glorified.

This meeting is not a failure. It is a success. There will be no envy after

tonight. God is awful in Zion. Woe be unto those who are obstacles;

woe be unto those who are obstacles."

A section of the congregation makes another attempt to sing, and the

hymn "Dyma Gariad fel y moroedd" is started, but the revivalist

peremptorily calls upon them to stop. "No, there is to be no singing just

yet. We may have singing presently. It is beginning to lighten. You can

pray as much as you like, but the only subject of prayer now must be

these five. No praise, and no prayers for salvation."

Five minutes later, after innumerable prayers have been offered, singly

and in chorus, Evan Roberts, with face streaming with tears, declares that

"All who are here must before they retire to rest tonight interceed to God

on behalf of the five. Now we shall sing, and let us sing.

"Duw mawr y rhyfeddodau maith!

Rhyfeddol yw pob rhan o'th waith."

Great God of wonders! all Thy ways are matchless, Godlike and divine!

But the fair glorys of Thy grace more Godlike and unrivalled shine.

Who is a pardoning God like Thee?

Or who has grace so rich and free ? - President Davies.

There is no need to repeat the permission. The congregation seizes the

opportunity with avidity, and finds refreshing relief for its pent-up

feelings in the noble strains of "Huddersfield."

Still the congregation is loth to depart, though 10 o'clock is now long past.

Miss Roberts reads the story of the prodigal son, punctuating it with

quaint and picturesque comments as she proceeds. After this the meeting

is again tested, and a shoal of converts is added to the already large list.

Above the clock sits a man, who to the stewards has declared he cannot

surrender, for he is not ready. Under the gallery is another man, of

whom it is announced that he lacks not in knowledge of the plan of

salvation, but he declines to surrender. Looking in turn at the two, the

revivalist is heard to remark. sotto voce, that the man over the clock will

give in, but the one under the gallery is to be left alone. A few minutes

later the first-named is seen to collapse in a paroxysm of grief. He has

surrendered, and once more the chapel rings with the strains of "Diolch

lddo". This brings the total number of converts at this one meeting up to

70.

In response to the missioner's request the congregation stands, and in one

great volume of sound repeats after him, thrice in Welsh and thrice in

English, the verse, "Believe in the Lord Jesus Christ, and thou shalt be

saved." "There," he declares, "that verse will ring for years to come in

the ears of scores that are present, and let none of you come into any

more of these meetings without first asking God to save."

"This," declares the Rev. John Williams, "has been a meeting we shall

remember for ever, but we who are church members have room to show

more of the spirit of self-denial. A large number of non-adherents, for

whom this meeting was intended, have been turned away because

hundreds of you members who are here ought to have been at home."

Thus ended one of the most remarkable gatherings yet held.

Back to the city I travelled with a number of Liverpool Pressmen, to

whom this had been a first experience of the revival. "What think ye of it

all?" asked one of the others. "My thoughts are too tumultuous for

expression," was the reply elicited, "but this man Roberts seems to me to

be beyond human comprehension."

On Sunday, Mr. Evan Roberts enjoyed a rest, but in the afternoon

accompanied by the Rev. John. Williams, he paid a surprise visit to the

Princes Road Welsh C.M. Sunday School, and there officiated at a

distribution of prizes.

The Missioner as Thought Reader.

LIVERPOOL, Monday.

The startling declaration of Mr. Evan Roberts at the Shaw-street meeting

on Saturday night that there were present five persons envious of the

work of saving souls then proceeding, and that three of the five were

preachers of the gospel will be recalled.

A Liverpool barrister, in a letter to the "Liverpool Daily Post," writes "I

was present at the meeting and at that period when the names of converts

were being taken. A minister was standing close behind me. Just then

another minister came up to him having a piece of paper, apparently with

the names of converts on it. The latter minister said to the first minister in

reference to a young man whose name he had taken, and who had

prayed with great fervour, "It's all humbug," and then went on to

mention a charge, which would show that the said young man was not fit

to be a member of a church. Then the first minister began to speak about

Evan Roberts, and said, 'I have heard him at Princes-road and at Anfield,

and I see nothing in him! The second minister agreed, saying, 'I see

nothing in him either.' It was shortly after this that Evan Roberts went

into a paroxysm, and made the declaration about the five persons - three

of them ministers - who were full of envy and jealousy. I relate the

story without any comment. Evan Roberts certainly has the rare gift of

saying the right thing at the right moment."

This letter has aroused great interest, and is being keenly discussed. The

writer, however, is not quite correct. Mr. Evan Roberts did not say,