EVAN ROBERTS

His Life and Work.

By J. Tudor Rees

About This Book

We know little of the author of this work, except that he authored this

work, which is the first of a six-part series. The copy we have was taken

from a photocopied article in the Sunday Companion. The date is

unknown. When we find the other five we will add them to this

collection. This lively account was penned in 1905 when the revival was

still powerfully affecting the Principality, making it a very lively account.

We also know that J. Tudor Rees was a lawyer from London and that he

toured Canada and America in early 1906 to propagate the message of the

Welsh Revival, accompanied by Gwilym O. Griffiths and Dewi Michael, a

preacher and singer, respectively.

In the lonely cottages that stud the rugged hills of Wales, in the coalmines

and railway-carriages, at the forge, and in the busy market-place there is

one whose name is on every tongue-and they call him the "Wesley of

Wales."

He was born on June 8th, 1878, in a tiny cottage at Loughor, a little

mining town near Swansea. Evan was one of seven sons, and his birth

was the occasion for much rejoicing in the humble home. Soon he went to

the National Schools, Upper Town, Loughor, and there manifested those

characteristics which he to-day exhibits in a more developed form. He

soon came to be regarded as a real little hero. He it was who saw that

right was done; to him went those who had a grievance to be settled.

One day he was told that a little chap had been cruelly treated by a boy

bigger than he. "Leave him alone!" said Evan. But the oppressor became

angry. Off went the lad's coat, and his opponent had a timely and welldeserved

thrashing. He never deigned to "copy" from another boy; and

although he would not allow anyone to do so from him, yet he was ever

ready to assist a less fortunate scholar in his studies.

He was not only a little hero, but was a sharp scholar also. "From the first

he beat us at everything," said an old schoolmate of his. Although he

never showed those qualities which stamp a boy as precocious, he was

almost invariably the top in his class, and the conscientious, fair way in

which he did his work, as well as the results achieved, were not only

commentated upon by the teachers, but were envied of all his fellowscholars.

And yet no one bore him any ill-will. "You could not help

loving the little fellow." said a teacher of his. "There was something

attractive about him. Ever fair and scrupulous, he won the admiration of

all."

At School And In The Mine.

His was an uneventful life. School and play, play and school; that was his

daily programme. "Have you been 'mitching' from school to-day, Evan?"

said his mother one day, when the boy returned home earlier than usual.

"Oh, no," he replied quietly; " I have nowhere else to go but to school."

He was always fond of books, and the bookcase in his home at Loughor

to-day contains many a story-book which he bought with his weekly

pennies.

The characteristics which he displayed at school he exhibited at home. He

was ever the first toassist his mother in her domestic duties. "He was

always a good boy," said Mrs. Roberts to me, when I visited her at

Loughor quite recently. " Whenever I wanted him to do anything for me

he never refused. And he was always so kind and sympathetic. He

always had a lot of friends as a boy, and was never tired of assisting them

in anything. Although always fond of studying, he used to play as much

as the other boys.

His schooldays were nearly over, and the lad was anxious to be earning

something. But his mother's heart was sad, though he knew it not. "I have

another son to serve God now," she said, after Evan's birth, and she had

silently nursed the hope that some day he would become a minister.

How, she knew not; but she hoped and hoped, and prayed oft and long.

Her prayer was not to be answered for a score of years.

Evan's father was employed at the Mountain Colliery, Gorseinon, about

two miles distant. One day there was an accident at the pit, and Roberts,

who had charge of a "district," had his foot crushed. Evan heard the

report while at school, and rushed home to see if it were true. Yes; it was

true enough, and the doctors said it would take four months before

Roberts could return to work.

He had been laid up for a little while, when the manager of the colliery

sent to ask him to endeavour to get back to the mine, and bring one of his

sons to assist him. Here was Evan's chance, and father and son set out

together. Not being able to walk about much himself, Mr. Roberts simply

gave the orders, and Evan did the running about. In a month or so the

injured foot got all right, and Evan then became "door-boy," opening and

shutting the doors in the pit. Later he became a "knocker" at the bottom

of the shaft, and ultimately a full-fledged collier.

With the pride of the unselfish lad that he was, he took home his weekly

earnings to his mother, and out of the "pocket-money" he had given

back to him he purchased books. Even while working in the pit he was

very religious, and was always praying, reading his Bible, or singing

hymns. Everyday he took a Welsh Bible down the mine with him and in

his spare moments read from its pages. When not in use, the Bible was

placed in a niche in the workings.

On January 5th, 1898, an explosion occurred at the colliery in which Evan

worked, and his precious Book was blackened and scorched by the fiery

blast. That Bible is to-day one of the revivalist's most valued possessions,

and as his sister opened the brown paper in which the broken pages are

stored, and gave me a few burnt leaves, tears welled up in her eyes.

It was just seven years before that the explosion happened, and the

sister's tale of Evan's escape-for he was quite unhurt-was singularly

touching. Another souvenir of his early days that was shown me was his

shorthand Bible.

"He learnt shorthand without any teacher," said Mrs. Roberts, with a

touch of pardonable pride. "He bought the books himself, and spent

many an hour in this room with his Bible." And as I scanned the unique

Volume, marked "Evan Roberts, Island Villa, Loughor," I detected the

traces of its having been much used.

Just at this time the youth became an active worker in the Methodist

chapel, and one incident alone is enough to prove his real interest in

things religious.

Early Efforts For Others

In order to provide for the spiritual wants of the miners' children, a

Sunday-school was opened in the colliery offices, and Evan became the

secretary of what was called "the ragged school," owing to the children

who attended it being for the most part ill-clad and poor. This office he

held for some time, and some of those who attended that school are living

in Loughor to-day, and look back with pride and pleasure upon those

bygone days. Even then the young man shed an influence which has not

ceased to this day.

Evan was also a tower of strength in the chapel. Out of his scant earnings

he gave liberally. He and a few others purchased a railing that was

deemed necessary around the chapel, and together they fixed it in

position. He had prayed the night before that they might have sunshine

to do the work, and the prayer was answered.

And thus it went on, nothing much happening to disturb the usual

monotony of the young man's life.' He was gradually growing weary,

and still more weary, of the hard work in the mine, and his longings to

enter the ministry became more accentuated as the days rolled on. "I used

to forget the seam upon which I worked," he says, "I thought so much of

religion."

One day he was discovered a mile or more from his "district." and upon

being asked the cause of his wandering, he said: "How strange! I had

quite forgotten where I was going." One of his old fellow-colliers says

that he well remembers how young Roberts would hew the coal to the

accompaniment of same Welsh hymn which he used to hum.

It was no unusual sight to see the young man on his knees in the dust and

dirt of the coal-mine, offering up prayer, and when not thus engaged he

would, when he could snatch a moment, be reading the Bible, of which I

have already spoken.

After leaving his work he used either to study or play with the boats on

the tide. He was fond of the chapel, but sometimes would miss an

occasional service. "Remember Thomas," said an old deacon to him one

day. "Think what he lost. And should the Spirit descend while you were

absent, think what you would lose!" These words produced an

imperishable impression upon the young man's mind, and for years after

that he used to attend a religious service in his chapel nightly.

"I will have the Spirit, be said to himself." "And through all weathers,

and in spite of all difficulties, I went to the meetings. Many times as I

went I saw other boys with the boats on the tide, and was tempted to

desert the meeting and join them. But, no. Then I said to myself,

'Remember your resolve to be faithful,' and on I went."

And this was the youth's weekly programme; Prayer-meeting, Monday

evening at Moriah Chapel; prayer-meeting, Tuesday evening at Pisgah

Chapel; society meeting, Wednesday evening; Band of Hope, Thursday

evening; class, Friday evening; and chapel all day on Sunday.

Throughout the weary years he spent hours in communion with God,

praying for a revival of religion in Wales. Sometimes he and a friend

would sit up for hours and hours at night talking about a revival, and

when not talking he would be reading about revivals. "I could sit up all

night," he said, "to read or talk about revivals. It was the Spirit that

moved me thus." Nor was this desire of a short-lived nature. He had

prayed and read and talked for ten or eleven years about revivals.

He Leaves The Mine

Even Roberts was what is called in Wales a "union" man, and a strike of

unionists in the colliery wherein he worked threw him out of

employment. Nor was he altogether sorry. He had grown tired of the

wearisome work in the mine, and now thought hard about his future, for

he was always ambitious. He wanted to be a missionary; but, no, he could

not be, and ultimately he decided to become apprenticed to his uncle at

Pontardulais, near Swansea, who was a blacksmith. This was in January,

1903. Having some hard-made savings by him, he paid £6 thereof for the

privilege of becoming apprenticed, and bound himself for two years.

"A remarkable thing happened to Evan one Sunday." said the revivalist's

mother to me, a little while ago. "As was his custom, he had attended the

Sunday services, and was, as usual, very tired. But there was something

peculiar about him. At first he did not appear to be willing to talk much,

but he later told me that he had been face to face with God. For years he

had prayed for a baptism of the Spirit, and his prayers were partly

answered that night."

Did he pray much at home?" I ventured to query.

"Oh, yes!" replied Mrs. Roberts. " He used to spend hours in his own

room alone with God. Sometimes, I believe, he spent whole nights in

prayer."

He had been a year at the forge, and by this time had become a very

useful blacksmith; so his master was extremely sorry when he was

informed that it was the young man's intention to leave the smithy. But

persuasion was of no avail. The "tide" of the youths opportunities was at

the flood, and he decided to take advantage thereof, and go to school.

And an incident of peculiar interest took place just then. As is customary

in Wales, when a young man makes application that his college fees, &c.,

should be paid by the church, the members of the particular chapel have

to decide as to whether the candidate is to be supported or not. On the

Sunday evening when young Roberts's application came before the

communicants at Moriah Church, Loughor, some of those present were

some-what tardy in supporting it. The minister thought that the young

man had the fullest sympathy of the congregation, and could hardly

understand the apparent coldness. "Now, then," he said, "why are you so

slow? If you want the young man to go to college, why don't you stand

up?' And immediately all present rose to their feet, and Evan Roberts was

given the necessary permission to go to college to prepare for the

ministry. At length he could see the answer to his oft-repeated prayers.

Throughout long weary years he had been a diligent student, and now he

could devote the whole of his time to preparing for the entrance

examination of the Preparatory School at Newcastle Emlyn.

The young man's joy knew no bounds, but yet there was sadness. There

was an obscurity which he could not penetrate. He longed to be doing

something for his fellow-man. He felt there was a great task before him.

During the day he was all alone, and at night some friends would

occasionally drop in. And then the only subject he cared to discuss was

revivals.

Long Nights Of Prayer

"I could sit up all night to read or talk about revivals," He says. "It was

the Spirit that thus moved me."

Even while studying, his mind would oftentimes be elsewhere than on

the subject under consideration. He could see the raging angry billows

whereon myriads of souls were being tossed, and he longed to "throw

out the lifeline." Gradually he grew nearer amid nearer the Light. He

prayed almost without ceasing." Sometimes, when his mother went into

his room to call him to a meal she found him on his knees.

"He used to say," said Mrs. Roberts to me a short while ago, that prayer

was more important to him than food."

One night, while praying by his bedside, he was "taken up to a great

expanse "-I will give his own words-"without time or space. It was

communion with God. Before this I had a far-off God. I was frightened

that night, but never since. So great was my shivering that I rocked the

bed, and my brother, being awakened, took hold of me, thinking I was ill.

After that experience I was awakened every night a little after one o'clock.

This was most strange, for through the years I slept like a rock, and no

disturbance in my room would awaken me. From that hour I was taken

up into the Divine Fellowship for about four hours. What it was cannot

tell you, except that it was Divine. About five o'clock I was again allowed

to sleep on until about nine. At this tune I was again taken into the same

experience as in the earlier hours of the morning until about twelve or

one o'clock."

Seeing that he was supposed to give all his time for college preparation,

his family were naturally curious to know why Evan did not get up

earlier. While at the colliery and the forge, he rarely, if ever, lost any time

through over-sleeping, and why he should now lie abed so late no one

could understand. But all questions on this head were not satisfactorily

answered. It was too Divine to say anything about, "he says. "I cannot

describe what I felt it, and it changed my whole nature."

This went on for three months, and during that period he occasionally

preached at one or two of the neighbouring chapels.

"Not much use your going to college," said a pastor, after one of the

young man's efforts. "You are a preacher already!" But Evan simply

smiled. Certain secrets he possessed, and these he gave to no one. "God

had told me," he says, "that I was to take part in a great revival; but kept

the secret to myself."

Early Preaching Efforts.

But to preach was always somewhat of an ordeal, He was passionately

fond of it, but the mental anxiety and soul-worry must surely have told

upon him.

"Because he was never over-strong," Mrs. Roberts informed me. "After

preaching he would come home very tired, and sometimes done up. His

chest used to trouble him a great deal; but now, thank God, he is all

right."

With preaching and praying, his time was much encroached upon, and

the hours devoted to study became proportionately less. And when the

eventful examination day came the student considered himself somewhat

ill prepared for the ordeal. But prayer sustained and encouraged him, and

he got through the examination without much difficulty. "But Evan

says," declares his mother, "that he does not know how he passed. How

God must have helped him "

It now remained for the young man to enter college, and, packing up his

belongings, not without some sad regrets, he proceeded, at the

commencement of 1904, to the Preparatory School, Newcastle Emlyn. But

of all his sorrows at leaving home, the greatest was his fear lest the sweet

communion with God which he had enjoyed for so long should cease.

"I dreaded to go to college," he says, "for fear I should lose those four

hours with God every morning. But I had to go, and it happened as I

feared. For a whole month He came no more, and I was in darkness."

Roberts decided to give up half an hour every day to communion with

God; but such planning and organising his Master did not seem to

favour. At the end of the first month at the school the darkness became

pierced by a Light unspeakable. The old joy returned, and once more he

communed with God, "as with a friend, face to face." As the days wore

on he became less inclined to study, and more inclined to pray and read

the Bible. And soon, as he himself says, "all the time was taken up" in

those religious devotions.

To study was all right; but-but-but he was straining towards a

nebulous something.

Dissatisfied-or, rather, unsatisfied-at home, he was the same at college.

He could not yet understand God's purpose in his life.

The critic says that Roberts is nothing; but, eliminate the human as much

as you like, you are bound to reckon with the charming, forceful,

captivating personality of the revivalist. The active brain and powerful

individuality of the student made it as easy for him to have lived an

obscure life in his humble village at Loughor as for General Booth to have

kept within the limits of his Methodist circuit, or Wesley in his tiny

parsonage at Epworth. The youth was brimming over with a zeal that

soon was to be shed in all directions.

At college, as at home, he frequently wrote poetry, and some of it was of

no ordinary merit. His mother told me that often he would go and sit

alone on the hillside, and do no small amount of rhyming. Hs was a

poetic soul, and he sought to give expression to the thoughts that haunted

him when alone with Nature.

Much of this poetry has appeared in the Golofn Cymraeg (Welsh column)

of the "Cardiff Times" under the revivalist's bardic name, "Bwlchydd."

He frequently sent his MS. to that eminent Welsh poet, Rev. Elvet Lewis,

who criticised the verses of his ambitious student.

The Revivalist's College Days.

The first few months of Roberts's college days were uneventful, and his

fellow-students, who were passionately fond of the future revivalist,

could detect nothing very extraordinary about the young man. He never

outshone his fellows, was never a recluse or bore, and entered into

college life with customary life and spirit.

But what a struggle was going on within! "Something" told him his

studies were soon to he interrupted, that a vast field of labour spread

itself before him. But, alas! he seemed to he losing his hold upon God! In

the autumn of 1904 he contracted a severe chill, and had to spend four

days in bed.

"The last night of the four," he says. " I was bathed in perspiration- the

result of the cold, and communion with God." That was on Saturday. On

the following 'Tuesday evening a fellow student, Sidney Evans-who is

now a prominent revivalist-went to see him, and asked him to go to a

prayer-meeting which was to be held in a neighbouring chapel. Although

he had not made up his mind to go before his friend arrived, some

mysterious power impelled him to go.

"At that moment," he says, "I felt the Spirit coming upon me, and so

irresistibly did he come that I rushed to the chapel without my top-coat."

While at that meeting the influence began. Roberts had "liberty before the

Throne of Grace." He was "ready to pray," so he says, and he prayed

specifically for some young women who were at the meeting from New

Quay. Although by no means a sensational service, there was an

influence there that quickened the young man's life and feelings.

On the following evening he attended a prayer-meeting again; but this

time he had become somewhat cold. He did not pray publicly, but

silently he lifted up to heaven petitions for the removal of his

indifference. His own words paint the picture: "I was hard. I could, look

at the Cross without feeling, and I wept for the hardness of my heart, but

could not weep for Christ. I loved the Father and the Spirit, but I did not

love the Son."

Pleading For The Fire.

In great anguish of soul, he left the service and spent the night in great

mental distress. The chief joy of his life seemed to be vanishing,

notwithstanding his sincere attempts at its retention. Something was

wrong. On the following day he was on his way to a village handy-

Blaenannerch-and called at the house of the Rev. Evan Phillips. The first

man he met was a well-known local railway-guard, and to him he laid

bare the secrets of his breaking heart.

"I am like flint," were his pathetic words. I feel as if someone had swept

me clean of every feeling." Sympathetically did the elder Christian listen

to the plaint of the student, and the words he uttered somewhat salved

the young man's heart. Looking back upon that experience, he says: "It

was my conviction then that I must either be cast upon a bed of affliction,

or receive the Spirit mightily." It was the latter that happened.

While he was speaking to the guard a prayer-meeting was in progress in

another part of the house. But he did not go in. And this for two reasons.

First, lest they should reprimand him for venturing out while in delicate

health; and secondly, because he wished to speak to one of the family

"about the state of her soul."

The interview between "Mag" Phillips and Roberts was singularly

pathetic. After some conversation on Scriptural matters, the young man

said: "You pray for me, and I'll pray for you," whereupon the other burst

forth into tears. Yes; he felt his need of Divine help. Apart from his

natural weakness, nothing but the Sun of Righteousness could thaw the

icy hardness of his heart. And He did.

"Both of us were blessed the same day," he avers. "I in the morning, and

she in the afternoon. I received something about half-past three. I asked

Mag if she had been praying for me at that time, and she said: "I was

praying for you all day, Roberts bach " (a Welsh term of endearment).

The rays of the Heavenly sunshine were piercing the gloom; but still there

were clouds, and the young man's sadness remained. On the way home

front Blaenannerch lie spoke to several who had attended the prayermeeting

regarding the state in which he found himself. But relief came

not. "We can do nothing for you?" they wistfully queried. "No," was the

sad reply "I have only to wait for the Fire."

And he had not long to wait, for at half-past nine next morning the Fire

fell, and it has been burning over since.

But even that experience did not completely lift the clouds of depression

that hung about him. He brooded over-not so much himself now, but

the apparent failure of Christian agencies. He took a walk in his garden,

and there saw a vision which was as remarkable as it was significant.

The Vision Of The Sword.

While in the Slough of Despond he looked to the hedge on the left, and

there saw a face full of scorn, hatred, and derision, and heard a laugh as

of defiance. It was the prince of this world, who exulted in the young

man's despondency. But this figure was not suffered to exist long.

Suddenly there appeared another Form, gloriously arrayed in white, Who

bore aloft a flaming sword. The sword fell athwart the first figure, and it

instantly disappeared. The significance and moral of the vision will be

demonstrated later. Roberts straightway informed his minister of what he

had seen, but was told that the despondency which he was in might very

easily have produced an imagination of a vision, "But I know what I

saw!" he declares. "It was a distinct vision. There was no mistake."

On the Thursday morning, he, in company with a few others, started

again for Blaenannerch about six o'clock in the morning. Several meetings

were to he held that day, and great things were anticipated. At seven

o'clock the first service began. Then the Rev. Seth Joshua, a popular

preacher in South Wales, prayed, and made use of words that seemed to

be specially meant for Evan Roberts. "Lord, do this, and this, and this,

and bend us," he petitioned.

In speaking of this prayer, the revivalist says: "He did not say, 'O, Lord.

bend us." It was the Spirit that put the emphasis for me on 'bend us.'

'That is what you need,' said the Spirit to me. And as I went out I prayed:

'O Lord, bend me!'"

After the meeting the company repaired to the house of the Rev. M. P.

Morgan for breakfast. The others were joyful, but in Evan's heart a

contest was in progress. " Bend me, O Lord, bend me!" was his constant

prayer. He was realising that before he could be used "self " must be

crucified. He wanted to be used, and therefore desired that his own

nature should be "bent." As he has himself said, it was a stern battle. But

Jehovah conquered!

At the breakfast-able he was offered some bread-and-butter. "But I

refused," he says. "I was satisfied. At the same moment the Rev. Seth

Joshua was putting out his hand to take the bread-and-butter, and the

thought struck me: Is it possible that God is offering me the Spirit, and

that I am unprepared to receive him? That others are ready to receive, but

are not offered?'

The thought was distressing, overwhelming, and his "bosom was quite

full-tight."

Having partaken of a scant breakfast, he, with the others, hastened to the

nine o'clock service. "We are going to have a wonderful meeting today,"

said one. Roberts's rejoinder was: "I feel myself almost bursting." The

service was opened in the usual way, and then everything was left in the

hands of the Spirit." Prayer succeeded prayer, and hymn followed hymn.

But Roberts was silent. He longed to pray, but the Spirit forbade his doing

so.

"Shall I pray now?" he inquired of the Spirit. "Wait a while," said He.

And as time went on the young man, still under the restraint of the Spirit

became more and more agitated. "I felt a living force come unto my

bosom," is his comment on that wonderful experience. "It held my

breath, and my legs shivered; and after every prayer I asked: 'Shall I pray

now?' The living force grew and grew, and I was almost bursting."

And then he prayed, and it was a prayer that affected all those present.

He could he restrained no longer. "I should have burst if I had not

prayed," he says. He fell on his knees, and flung his arms over the seat in

front of him. Tears and perspiration flowed copiously, and a good lady

who sat near by wiped the tear-stained face. "For about ten minutes it

was fearful. I thought blood was gushing forth."

He cried, in passionate accents: "Bend me! Bend me! Bend me!" And then:

" Oh, oh, oh, oh!"

"Oh, what wonderful grace!" said a woman who sat near by. And the

audience sang with great feeling: "I hear Thy welcome voice."

When The Blessing Came.

His prayer was answered. The battle was at an end. "After I was bent,"

says Roberts, "a wave of peace came over me." Then the desire which he

always had to do something towards the declaration and salvation of his

fellows became accentuated. Now, indeed, he must be up and doing. But

where and how was he to start?

The salvation of souls became the great burden of his heart. "From that

time I was on fire with a desire to go through all Wales; and, if it were

possible, I was willing to pay God for allowing me to go."

A little company of eight met together, and devised a plan of carrying the

flame of salvation all through their beloved land. But how God overrules

the planning of his creatures later events were to show.

He had but little money. The hard-earned savings bad been considerably

reduced alter paying school-fees and other necessaries. But the optimistic

youth said he would pay all expenses of the tour! Now he thought of

nothing else. At length he saw that God was going to use him in a mighty

manner and his delight was immeasurable. On the following Saturday

afternoon a few, of the eight went down to New Quay "to confer about

the idea," and further to mature the somewhat hastily made plans. For

two hours they discussed the question, and then Evan left for Newcastle

Emlyn - "for the sake of one soul."

But the others did not leave. "They remained there and prayed over the

plan, but no light came." And the little company dispersed without

having arrived at any definite decision.

So far as these young people were concerned, darkness prevailed; but

Evan Roberts soon came into possession of that Light that never was on

sea or land. God commanded the young man to go home, and open his

great work in his old town.

"I will go willingly amongst strangers, Lord, but it will be so hard to

work amongst my own people!" And thus he for a time disobeyed God's

Spirit. But he was not to go his own way.

One Sunday night, feeling troubled and ill at ease, he went to his chapel

at Newcastle Emlyn. But what happened he knew not. Right through the

service he was enveloped in a great glory. Before his astonished gaze was

the school-room of his native town. "And, there sitting before me," he

says, "I saw my old companions and all the young people, and I saw

myself addressing them.

"I shook my head impatiently, and strove to drive away this vision, but it

always came back. And I heard a voice in my inward ear as plain as

anything, saying: 'Go and speak to these people.' And for a long time I

would not. But the pressure became greater and greater, and I could hear

nothing of the sermon.

"Then at last I could resist no longer, and I said, 'Well, Lord, if it is Thy

will, I will go.' Then instantly the vision vanished, and the whole chapel

became filled with a light so dazzling that I could faintly see the minister

in the pulpit, and between him and me the glory as the light of the sun of

heaven."

On The Eve Of Revival.

Home went the young man, with mingled feelings of joy and sadness.

Glad because he had seen this wonderful vision; sad because it was so

hard to obey the command of the Master. There was one whom he felt

bound to confide in, and that was his tutor. To him went Evan, and

opened his soul. Was he dreaming, and was the vision "of God or of the

devil?"

The professor was not slow to discern that his student had recently

passed through a wonderful spiritual experience, and became anxious to

advise him in the right way. Very kindly and sympathetically he listened

to the young man's tale, and then checked his arguments by saying: "The

devil does not put any good thoughts into your head. This vision and

command must come from, God."

Then Evan became cheered. Here was an advice which he valued, and he

at once acted upon it.

But before he attended another service at Newcastle Emlyn, and another

vision which he saw there deeply affected him. No disobedience after

that. The "call" had come, and he now could not choose but go. "While

listening to the sermon," he says, " I received much more of the Spirit of

the Gospel from what I saw than from what I heard. The preacher did

very well, was warming to his work, and sweating by the very energy of

his delivery. Mud when I saw the sweat on the preacher's brow, I looked

beyond, and saw another vision-my Lord sweating the bloody sweat."

No hesitation now; no halting. It was time, he thought, for him to be up

and doing. But to leave college was not an altogether pleasant task. He

had made friends, and it was rather a wrench to leave them. As it

happened, he was suffering from a cold, and his fellow-students thought

that Evan had gone home because he was unwell. But a few knew the real

secret of his departure. One of these was Mr. Sidney Evans, whom Evan

Roberts wired for directly he saw that the " fire " was spreading.

So, with a heart now glad, anon sad, the young man who was to be the

means of quickening the life of Wales, and setting on fire the whole of the

country, went to his humble home at Loughor. Nor did he dream of the

vast work that lay before him.

When Evan came home," said the revivalist's brother Dan to me a short

time ago, "he had something about him that was peculiar. Now I see it

was the revival spirit. My eyes were very bad just then, and I was home

from work. If you remember, it was just at the time of the terrible railway

accident at Loughor. 'Your eyes will soon he all right,' said Evan to me.

'Do you think so?' I inquired. 'Yes,' came the reply. 'The Lord has need of

you.'

"Evan and I spent a great deal of time together, but one day I left him to

go to see the doctor in Llanelly about my eyesight. And-would you

believe it?-I have never been troubled with my eyes since. Evans words

came true."

"The Lord has need of you!" These words rang in Dan's mind. What

work was he to do? "For," said he, "I never was what you might call an

active Christian. And when Evan said that God had need of me, I

wondered what he meant. But very shortly I was to know."

"It all seemed so strange to me," said Dan, "I could not understand it.

And why Evan should say, 'The Lord has need of you' I could not

imagine. I had been superintendent of the Sunday-school, and did other

Christian work; but I was not out-and-out. But my brother soon dispelled

all my doubts and coldness."

In a day or two Evan's cold was all right, and he went to the pastor of

Moriah Church to get his permission to hold a special week-night service

in the chapel.

A Discouraging Start.

The proposition, however, was viewed with a certain amount of

suspicion. There was not much life in the church, and few would attend

the service. But that made Evan more determined. Not much life!

Therefore, the need for an awakening. But the young man had yet a

certain amount of trepidation. To get a meeting, and let it be a failure! It

was too dreadful to think of.

So, without much delay, he set out to see one or two of the older deacons

- not to get their opinion as to the advisability of convening a meeting,

but for their permission. He was told the ground was hard, but he should

try. That was enough for him. He felt that every obstacle had now been

removed, and that he was in a position to proceed to the commencement

of a movement which he felt would envelop the whole land. He was

beginning to realise the great work that lay before him.

But still he had his qualms. Now buoyant, anon despondent, his feelings

were those of mixed joy and sadness. The state of his mind can be

imagined from his own words.

"When I go out to the garden," he said, "I see the devil grinning at me;

but I am not afraid of him. I go into the house; and when I go out again to

the back I see Jesus Christ smiling at me. Then I know all is well." And so

it was. Feelings of despondency alternated with moments of exuberant

joy. But the latter were soon to supersede the former, as prayer

strengthened his purpose.

A statement which he made a short time ago reveals the evolution-if it

can be so called-of the revivalist. "Some people," he said, "have called

me a Methodist. I do not know what I am. Sectarianism melts in the fire

of the Holy Spirit, and all men who believe become one happy family. For

years I was a faithful member of the Church, a zealous worker, and a free

giver. But I found out I was not a Christian; and there are thousands the

same. It was only when I made that discovery that a New Light came into

my life."

Being "all on fire," he spoke to all whom he came across as to

(1) whether they were converted:

and (2), if so, had they received the baptism of the Holy Ghost?

The Revivalist And His Mother.

One day, after having spent some time on his knees in his tiny room, he

went out to his mother. Placing his hand upon her shoulder, he said, with

a tremor in his voice, and a strange light in his eye:

"Mother, you have been a Christian for a number of years, and a good

Christian mother you have been. But-but, mother, there is one thing

more that you require."

Mrs. Roberts, astonished and visibly a affected, looked into her son's face,

and wistfully queried what that one thing was.

"Mother," replied young Evan, "the one thing more you need is the

baptism of the Holy Ghost." So unexpected was the message, so strangely

was it uttered, that the mother said little, if anything, to her son about

what he had spoken to her.

"But for eight days." she said, " I pondered his words over in my heart,

mentioned the incident to nobody, and prayed God that He would

baptise me with His Holy Spirit."

Day after day did she utter that earnest petition, but the Heavens seemed

as brass. There was no answer; and then, on the eighth day, " he fire

descended," and the joy of Mrs. Roberts knew no bounds. "And, oh,

what a change has come over me-and not only over me, but over the

whole family since then!" she said. "Yes, a wonderful change," says the

revivalist's brother. "It is not like the same place."

That was Evan's first bit of revival work; and, having been the means of

transforming his home, he set out to transform Wales, and, through

Wales, the world.

Before leaving Newcastle Emlyn he had prayed that God would "fire" six

souls at his first meeting. And, as we shall see, that prayer was answered.

He did not print bills, or advertise in the papers, nor have it announced

that a meeting for the young people would be held. Quietly and

unostentatiously he got amongst the young people of the church of which

he used to he a member, and very kindly and persuasively invited and

induced some of them to come together for a "talk." He told them that

God was about to do great things in Wales, and he wanted to have a talk

and prayer on the subject.

A night was fixed, and the young revivalist, although proving the words

of the minister to be partly true-"The ground is stony, and you will have

a hard task"-yet saw quite plainly that it was no false "call " that he had

received.

But not more than sixteen or seventeen of the young people actually

assembled. "I asked the young people to come together," says Roberts,

"for I wanted to talk to them, and, behold, it was even as I had seen it in

the church at Newcastle Emlyn. The young people sat as I had seen them

sitting all together in rows before me, and I was speaking to them even as

it had been shown me.

It was, indeed, a novel experience for young Roberts; and although he felt

convinced he had a message for them, yet it was with no small amount of

misgiving that he stood up to address those with whom he had

associated as an ordinary workman but a short while before.

"A prophet is not without honour, save in his own country." Evan

Roberts proved the truth of this. Had he called together a few young

people in a strange town he would probably have been accorded a

warmer sympathy. So the meeting was cold.

Signs Of Revival.

HE found, as he had been warned, that the "ground was stony." Nothing

daunted, however, he proceeded to break up the fallow land. "At first

they did not seem inclined to listen," he says, with a touch of sadness,

"but I went on, and at last the power of the Spirit came down, and six

came out for Christ." This indeed, was cause for thankfulness, and the

young man was encouraged to go on. The revival had commenced.

"But that did not satisfy me'" is Roberts's comment. "'O Lord,' I said,

'give me six more. I must have six more!' And we prayed together."

Prayer after prayer was offered, lighter and still lighter became the

leader's heart. The "hardness" was being removed, and the building

seemed aglow with the light of Heaven. Some mysterious power had

descended upon all present.

At length the seventh came," says Roberts, "and then the eighth and the

ninth together, after a while the tenth, and then the eleventh, and last of

all came time twelfth also. But no more." The stopping at twelve-the

number of converts asked for-stimulated Roberts, and this for more

reasons than one. He was thankful, in the first place, because it convinced

him of the Divine origin of his mission, and in the second, as he himself

says, because those present "saw that the Lord had given me the second

six, and they began to believe in the power of prayer."

So great was the power in that meeting, so overcome were the young

people with a holy emotion, that hour after hour slipped by, and they felt

no desire to leave. And when they actually left the building it was not to

go home. They must needs discuss the "wonderful times " here and there

at street corners with their friends. It was, indeed, good for them to be

there, and on leaving the chapel it seemed as if they were withdrawing

front the very gates of Heaven. So they decided to have another meeting

on the following night.

But even now the young revivalist could not exactly see God's purpose in

his life. What if his mission were a failure! What if the services fell

through! These thoughts, however, were not suffered to exist for long in

Roberts's mind. Prayer was his panacea-and still is. So that day he spent

no little time in the position of power invoking Divine guidance.

No special invitations or notices had been sent out about the second

service, and Roberts was not a little curious to know how many were

going to assemble in the chapel that night. Crowds he did not expect, but

he did anticipate power. Nor was he disappointed. That night there

gathered together a small company of two dozen or so. Not exactly a

"talk" that night. Prayer was the one essential. And the young people

seemed to begin that night where they left off on the night previous. No

hardness to remove; no ice to thaw. The fire was there. Neither were they

unaware of the fact. And as one of those who has had a big part to play in

the revival said: "Did not our hearts burn within us?" As a second

observed: "We were all on fire."

Again prayer succeeded prayer, and song followed song, and the hours

slipped away unconsciously to those praying men and women. And how

reluctantly did they leave the building. "It was a wrench," says one-a

statement not difficult of believing.

Loughor is but a small town, and at this time it had fallen into a sort of

spiritual slumber not unknown to the other towns in Wales. But those

two wonderful services had set the place agog with excitement. It was the

one topic of conversation. When was there to be another similar service?

Who instructed Evan Roberts to undertake the task of holding these

strange services? Those who had actually been in those "Pentecostal

meetings" were plied with questions in the pit, in the shop, in the street-

wherever they might be. Through that day the local prophets saw in Evan

Roborts's return home a meaning which before was unsuspected, and

made prophecies which subsequent events have fulfilled.

Little wonder was it, therefore, that the little company was greatly

augmented at the third meeting.

"First I tried to speak to some other young people in another church, and

asked them to come," says Roberts. "But the news had gone out, and the

old people said: 'May we not come, too?' And I could not refuse them. So

they came, and they kept on coming, until the chapel was crowded in

excess, hundreds having to be turned away."

The Fire Spreads.

The young revivalist was more than delighted, and he laughed

boisterously for very joy. One after another professed conversion, one

read, another prayed, and the scene witnessed that night-with a

hundred simultaneous prayers, people fainting, mighty singing-beggars

description. This meeting did not conclude until 4.30 on the following

morning.

But Roberts could not remain long at Loughor. He had accepted a

"supply" to preach at Trecynon, and hastened there on the following

Saturday to keep his appointment. But instead of a preaching service,

there was a revival meeting; and the "fire" that had set ablaze the

enthusiasm of the people at Loughor manifested itself at Trecynon also.

Wonderful times were experienced at this town, the meetings being in

some cases prolonged throughout the whole night.

As Roberts himself says: "I am on the Rock; nothing can move me. Prayer

is everything." Before going to stay at a home, it is made known that he

wants a room to himself, wherein he can go through those religious

devotions which are so essential to him undisturbed. A little while ago, I

was having tea at the same house as the revivalist, but could not enter his

room until a signal was given me. And that signal was his coming out of

his room and entering the apartment in which I sat.

With the few of us present he chatted pleasurably, and, on returning to

his room with Mr. Roberts, I handed him my diary, with the request that

he should give me the thought that had encouraged him, and which he

considered would be helpful to me. And then, turning over the leaves

until he came to June 8th, he said: "This is my birthday." Then he wrote:

"Ask, and ye shall receive.-EVAN ROBERTS." "That is all," he said.

"God has made promises. Keep Him to his Word."

One of his co-revivalists one day called the leader of the revival "Mr.

Roberts." "What do you mean by that?" was his query. "I know you have

two brothers already. Well, I will make the third. I am your brother. And

my name is Evan."

And talking about his name reminds me of a quaint remark which he

made one day. "The papers," he said, "and the people call me Evan

Roberts. That is very good of them. But I will stick to the John myself."

it is not generally known that the revivalist's full name is Evan John

Roberts.

About His Father's Business.

During the few days which He spent at home at Christmas-time the

humble cottage in which he lived was so besieged that, as his mother told

me, "he had to go out for long walks." And one day he performed an

action which reveals the loving nature of the man.

A little blind girl lived near by. She had heard a lot about the revivalist,

and would have given all she had to speak to him. So one day, unbidden

and uninvited, Roberts paid a visit to the lonely little girl, and spent over

an hour with her, telling her of all the wonderful things that had

happened. No one knew where Evan had gone to. But he was bent on

cheering the little one's heart. And he did. He was "about his Father's

business," for he was performing a kindly action unto "one of these My

little ones."

Christmas Day he spent quietly at home, attending his old chapel once

during the day. But how he was sought after! "The young people came to

him," said his mother, "just to shake him by the hand, They said new life

came into them by coming into contact with him." And all those who

have shaken the broad, iron hand of the revivalist can appreciate that.

"Now, then," he said to a friend one day, "let's have a proper

handshake-a decent grip." That grip, or grasp, is electrifying!

"Good-bye!" said a friend to Evan Roberts one day. "What !" said the

revivalist, with a touch of sadness. "Did you say good-bye?" "Yes," was

the reply; "I may not see you again." " Perhaps not down here," rejoined

Roberts; "but we'll be together up there, won't we? And that will be soon,

perhaps."

That "the Lord will provide" the revivalist never doubts; neither has he

cause to, in fact. Even when going by train, he has not to trouble about

getting tickets for himself. Kind friends are at the station with him,

wishing the young man good-bye and God-speed, and they are always

ready with the necessary passports.

One day, as I was pushing my way into one of the revival meetings with

the "singing apostles," a parcel suddenly appeared before my astonished

gaze. "Please give this to Mr. Roberts," said a shrill voice on my right. I

took the parcel, and found that it contained half a dozen linen collars!

And other articles he gets in the same way. "I have not to bother about

clothes," be said, on one occasion. " If I want anything new-well, it

comes."

One thing that strikes a person who has anything to do with the revivalist

is his humanness. Although profoundly spiritual, he is essentially human,

as those who know him best can testify. A humorous anecdote he

appreciates; nor is he destitute of a quiet humour himself.

"Do let me have your photograph, Evan !" said one who for some time

accompanied the revivalist as a helper. "What do you want with a

photograph?" queried Roberts. "You have the original all the time."

On another occasion the same person being brimming over for very joy at

the wonderful times experienced, remarked, "Is it not wonderful?" "Yes,"

replied the leader of the revival; "it is wonderful, but perfectly natural,

for God is natural, and naturally good."

A Sea Of Correspondence.

With correspondence the revivalist is deluged. Although his secretary.

Rev. Mardy Davis, does most of his secretarial work, yet Roberts receives

numbers of letters. One day when I was in his room there was a bundle of

letters almost a foot thick, and most of them days old. The letters of

application to attend certain towns, the revivalist just marks "Yes" or

"No," and forwards to his secretary.

Roberts is passionately fond of his mother language. One day while

talking in English to a young man, he queried: "Are you Welsh?" "Yes,

came the reply. "Well, then, we'll talk in Welsh," rejoined the revivalist.

And then ensued an animated conversation in "the language of Eden."

His absolute reliance on the will of God, his perfect obedience to the

dictates of the Holy Spirit, and his absolute faith in the promises of God

are truly remarkable. On one occasion I introduced a party of Christian

workers, who wished Mr. Roberts to visit a certain town, to the revivalist.

"Well," replied the young man, alter some thought, "my heart is there. I

am not unwilling to come, but the Holy Spirit tells me not to go there-

yet. I have been praying about it, and will continue to do so.

But of all the experiences through which the revivalist has passed, none

was so-shall I say it?-sensational as the seven days of silence imposed

upon him by the Holy Spirit. He was to see no one and speak to no one

for a whole week. Whenever he wished to communicate with those in the

house, or friends outside, he expressed himself by pen and ink. In a

written statement which he made, he said: "I must remain silent for seven

days. As for the 'reasons,' I am not yet led to state them. But one issue of

this silence is: If I am to prosper at Liverpool, I must leave Wales 'without

money'-not even a penny in my purse. We read of Ezekiel the prophet

that his tongue was made to cleave to the roof of his mouth, and that the

command was: 'Go, shut thyself within thy house.' My case is different. I

can speak, I have the power; but I am forbidden to use it. It is not for me

to question 'why,' but to give obedience."

Then follows a postscript in which he expresses his sorrow for the

disappointment his enforced silence would entail. "I am sorry," he says,

"to cancel my engagements. But it is the Divine command. I am quite

happy, and a Divine peace fills my soul. May God bless all the efforts of

His people!"

"It has been a difficult-a hard-week," were Mr. Roberts's first words

on emerging from his seven days' seclusion. "Not one word with anyone

for a whole week, but I felt it had to be gone though."

During his "great silence " the only person whom he saw was Miss Annie

Davies. In a memorandum-book, which he kept for giving and receiving

messages, he wrote on the first day of his seclusion: "There is no person

except yourself, Miss Davies, to see me for the next seven days, not even

my father and mother. I am not ill." Interspersed between these directions

are brief records of his daily experience. Of the first day of silence the

note says: "On the Tuesday, at 4.22 p.m., I asked the Lord for a message,

and received the answer: 'Isaiah liv. 10;' A Voice spoke plainly in English

and Welsh. It was not an impression, but a Voice. There was at this time a

struggle going on in my mind as to what the people would say!'

A Diary Of The Silence.

On the second day he wrote. "I cannot rend my Bible properly, for while I

read I may see some wonder, and just then give a word of acclamation,

and thus rob the silence of its power, for silence is a mighty weapon. I

would prefer being like Ezekiel, unable to speak. If I wore unable to

speak there would be no need for this watching. Yet, possibly the lesson

intended to be taught is to be watchful. I must teach myself to say with

my beloved Jesus, 'Thy will be done.'"

"11.30 third day-Saturday," ran the next entry in this remarkable diary.

"A wave of joy came into my heart to-day about 11.30. The sound of the

name of 'Jesus-Jesus!' uttered in my ear came to me, and I was ready to

jump for joy, and I thought He is enough for me-enough for all men-

enough for all to all eternity. On this third day I was commanded not to

read my Bible. The day would have been easier for me otherwise."

The next day was Sunday, and the note was written at 6.30 in the

morning. "Wait not," it said, "until thou goest into heaven before

beginning to praise the Blood. To praise the Blood in Heaven canot [sic]

bring any one soul to accept it. To praise is worthy; if thou canst by

singing the praise of Jesus on earth bring but one soul to accept Him it

will be a greater thing than all the praise beyond the grave to eternity."

"I have been very near to God this afternoon," runs the fifth day's entry:

"so near as to make me sweat. I must take great care, first, to do all that

God says-commands-and that only. Second, to take every matter,

however insignificant, to God in prayer. Third, to give obedience to the

Holy Spirit. Fourth, to give all the glory to Him, Here am I, an empty

vessel; take me, Lord." The last entry for that day was: "I have a mind to

shout "Three cheers for Jesus!"

On the sixth day a Voice commanded him to "Take thy pen and write." A

And this is a part of what he wrote:

"6.30 a.m. A voice: "The faith of the people is being proved as much as

thine own. Did I not sustain thee during your months on the pinnacle, in

sight of the whole world? If I could sustain thee in public, is My power

less to sustain thee in private? If I sustained thee during four months, can

I not sustain thee for seven days?" Following this came long extracts from

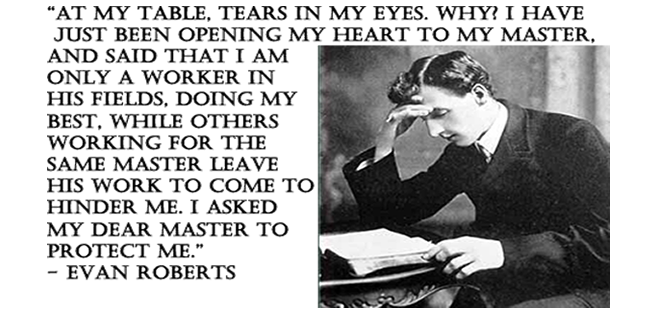

the Book of Isaiah. Under the heading " Seventh Day " the note is:

"5.17. At my table, tears in m eyes. Why? I have just been opening my

heart to my Master, and said that I am only a worker in His fields, doing

my best, while others working for the same Master leave His work to

come to hinder me. I asked my dear Master to protect me."

The next day the silence was broken-not to man, but to God. "I was

commanded to rise from my bed," he says, "bend my knee, open my lips

and pray. Then when I got out of the room I saw Mr. Jones, my host."

And thus ended a "testing period " unique in the annals of the history of

the Christian religion. As the revivalist said, "It was a lesson in

obedience."

And, now, I may be asked what I consider to be Roberts's "secret of

success." In a word, I consider it to be a transparent sincerity, a noble

humility, crucifixion of "self," and entire consecration to the will of God.

May he continue to be the lamp through which the Sun of Righteousness

shall send out upon the sad, dark hearts of our land His irradiating and

gladdening rays.

AUTO BIOGRAPHY

AUTO BIOGRAPHY BIOGRAPHY by G.FREDERICK

BIOGRAPHY by G.FREDERICK  EARLY LIFE OF C. G. FINNEY

EARLY LIFE OF C. G. FINNEY CHRONOLOGY OF HIS LIFE

CHRONOLOGY OF HIS LIFE A HISTORY OF OBERLIN COLLEGE

A HISTORY OF OBERLIN COLLEGE "NO UNCERTAIN SOUND"

"NO UNCERTAIN SOUND" THE MAN WHO PRAYED DOWN REVIVALS

THE MAN WHO PRAYED DOWN REVIVALS A MIGHTY WINNER OF SOULS

A MIGHTY WINNER OF SOULS A BIOGRAPHY

A BIOGRAPHY A BRIEF BIOGRAPHY

A BRIEF BIOGRAPHY MAN OF LIKE PASSIONS

MAN OF LIKE PASSIONS MEMORIAL ADDRESS

MEMORIAL ADDRESS REMINISCENCES

REMINISCENCES BIRTH PLACE

BIRTH PLACE BURIAL PLACE

BURIAL PLACE BIOGRAPHIES

BIOGRAPHIES

PHOTOS

PHOTOS

1. INTRODUCTION TO REVIVALS OF RELIGIONS

1. INTRODUCTION TO REVIVALS OF RELIGIONS 2. WHAT A REVIVAL OF RELIGION IS

2. WHAT A REVIVAL OF RELIGION IS 3. WHEN A REVIVAL IS TO BE EXPECTED

3. WHEN A REVIVAL IS TO BE EXPECTED 4. HOW TO PROMOTE A REVIVAL

4. HOW TO PROMOTE A REVIVAL 5. PREVAILING PRAYER

5. PREVAILING PRAYER 6. THE PRAYER OF FAITH

6. THE PRAYER OF FAITH 7. THE SPIRIT OF PRAYER

7. THE SPIRIT OF PRAYER 8. BE FILLED WITH THE SPIRIT

8. BE FILLED WITH THE SPIRIT 9. MEETINGS FOR PRAYER

9. MEETINGS FOR PRAYER 10. MEANS TO BE USED WITH SINNERS

10. MEANS TO BE USED WITH SINNERS 11. TO WIN SOULS REQUIRES WISDOM

11. TO WIN SOULS REQUIRES WISDOM 12. A WISE MINISTER WILL BE SUCCESSFUL

12. A WISE MINISTER WILL BE SUCCESSFUL 13. HOW TO PREACH THE GOSPEL

13. HOW TO PREACH THE GOSPEL 14. HOW CHURCHES CAN HELP MINISTERS

14. HOW CHURCHES CAN HELP MINISTERS 15. MEASURES TO PROMOTE REVIVALS

15. MEASURES TO PROMOTE REVIVALS 16. HINDERANCES TO REVIVALS

16. HINDERANCES TO REVIVALS 17. THE NECESSITY AND EFFECT OF UNION

17. THE NECESSITY AND EFFECT OF UNION 18. FALSE COMFORTS FOR SINNERS

18. FALSE COMFORTS FOR SINNERS 19. DIRECTIONS TO SINNERS

19. DIRECTIONS TO SINNERS 20. INSTRUCTIONS TO CONVERTS

20. INSTRUCTIONS TO CONVERTS 21. INSTRUCTION OF YOUNG CONVERTS

21. INSTRUCTION OF YOUNG CONVERTS 22. BACKSLIDERS

22. BACKSLIDERS 23. GROWTH IN GRACE

23. GROWTH IN GRACE 1.TRUE AND FALSE CONVERSION

1.TRUE AND FALSE CONVERSION 2.TRUE SUBMISSION

2.TRUE SUBMISSION 3.SELFISHNESS NOT TRUE RELIGION

3.SELFISHNESS NOT TRUE RELIGION 4.RELIGION OF THE LAW AND GOSPEL

4.RELIGION OF THE LAW AND GOSPEL 5.JUSTIFICATION BY FAITH

5.JUSTIFICATION BY FAITH 6.SANCTIFICATION BY FAITH

6.SANCTIFICATION BY FAITH 7.LEGAL EXPERIENCE

7.LEGAL EXPERIENCE 8.CHRISTIAN PERFECTION--1

8.CHRISTIAN PERFECTION--1 9.CHRISTIAN PERFECTION --2

9.CHRISTIAN PERFECTION --2 10.WAY OF SALVATION

10.WAY OF SALVATION 11.NECESSITY OF DIVINE TEACHING

11.NECESSITY OF DIVINE TEACHING 12.LOVE THE WHOLE OF RELIGION

12.LOVE THE WHOLE OF RELIGION 13.REST OF THE SAINTS

13.REST OF THE SAINTS 14.CHRIST THE HUSBAND OF THE CHURCH

14.CHRIST THE HUSBAND OF THE CHURCH 1 - MAKE YOU A NEW HEART & NEW SPIRIT (1)

1 - MAKE YOU A NEW HEART & NEW SPIRIT (1) 2 - HOW TO CHANGE YOUR HEART (2)

2 - HOW TO CHANGE YOUR HEART (2) 3 - TRADITIONS OF THE ELDERS (3)

3 - TRADITIONS OF THE ELDERS (3) 4 - TOTAL DEPRAVITY (Part 1)

4 - TOTAL DEPRAVITY (Part 1) 5 - TOTAL DEPRAVITY (Part 2)

5 - TOTAL DEPRAVITY (Part 2) 6 - WHY SINNERS HATE GOD

6 - WHY SINNERS HATE GOD 7 - GOD CANNOT PLEASE SINNERS

7 - GOD CANNOT PLEASE SINNERS 8 - CHRISTIAN AFFINITY

8 - CHRISTIAN AFFINITY 9 - STEWARDSHIP

9 - STEWARDSHIP 10 - DOCTRINE OF ELECTION

10 - DOCTRINE OF ELECTION 11 - REPROBATION

11 - REPROBATION 12 - LOVE OF THE WORLD

12 - LOVE OF THE WORLD THE REASONS FOR PUBLISHING

THE REASONS FOR PUBLISHING 1 - ETERNAL LIFE

1 - ETERNAL LIFE 2 - FAITH

2 - FAITH 3 - DEVOTION

3 - DEVOTION 4 - TRUE AND FALSE RELIGION

4 - TRUE AND FALSE RELIGION 5 - THE LAW OF GOD (1)

5 - THE LAW OF GOD (1) 6 - THE LAW OF GOD (2)

6 - THE LAW OF GOD (2) 7 - GLORIFYING GOD

7 - GLORIFYING GOD 8 - TRUE AND FALSE PEACE

8 - TRUE AND FALSE PEACE 9 - GOSPEL FREEDOM

9 - GOSPEL FREEDOM 10 - CAREFULNESS A SIN

10 - CAREFULNESS A SIN 11 - THE PROMISES (1).

11 - THE PROMISES (1). 12 - THE PROMISES (2)

12 - THE PROMISES (2) 13 - THE PROMISES (3)

13 - THE PROMISES (3) 14 - THE PROMISES (4)

14 - THE PROMISES (4) 15 - THE PROMISES (5)

15 - THE PROMISES (5) 16 -BEING IN DEBT

16 -BEING IN DEBT 17 - THE HOLY SPIRIT OF PROMISE

17 - THE HOLY SPIRIT OF PROMISE 18 - THE COVENANTS

18 - THE COVENANTS 19 - THE REST OF FAITH (1)

19 - THE REST OF FAITH (1) 20 - THE REST OF FAITH (2)

20 - THE REST OF FAITH (2) 21 - AFFECTIONS AND EMOTIONS OF GOD

21 - AFFECTIONS AND EMOTIONS OF GOD 22 - LEGAL AND GOSPEL EXPERIENCE

22 - LEGAL AND GOSPEL EXPERIENCE 23 - PREVENTING EMPLOYMENTS FROM INJURING OUR SOULS

23 - PREVENTING EMPLOYMENTS FROM INJURING OUR SOULS 24 - GRIEVING THE HOLY SPIRIT (1)

24 - GRIEVING THE HOLY SPIRIT (1) 25 - GRIEVING THE HOLY SPIRIT (2)

25 - GRIEVING THE HOLY SPIRIT (2) 1 - SANCTIFICATION (1)

1 - SANCTIFICATION (1) 2 - SANCTIFICATION (2)

2 - SANCTIFICATION (2) 3 - SANCTIFICATION (3)

3 - SANCTIFICATION (3) 4 - SANCTIFICATION (4)

4 - SANCTIFICATION (4) 5 - SANCTIFICATION (5)

5 - SANCTIFICATION (5) 6 - SANCTIFICATION (6)

6 - SANCTIFICATION (6) 7 - SANCTIFICATION (7)

7 - SANCTIFICATION (7) 8 - SANCTIFICATION (8)

8 - SANCTIFICATION (8) 9 - SANCTIFICATION (9)

9 - SANCTIFICATION (9) 10 - UNBELIF (1)

10 - UNBELIF (1) 11 - UNBELIF (2)

11 - UNBELIF (2) 12 - BLESSEDNESS OF BENEVOLENCE

12 - BLESSEDNESS OF BENEVOLENCE 13 - A WILLING MIND AND TRUTH

13 - A WILLING MIND AND TRUTH 14 - DEATH TO SIN

14 - DEATH TO SIN 15 - THE GOSPEL-SAVOR OF LIFE/DEATH

15 - THE GOSPEL-SAVOR OF LIFE/DEATH 16 - CHRISTIANS-LIGHT OF THE WORLD

16 - CHRISTIANS-LIGHT OF THE WORLD 17 - COMMUNION WITH GOD (1)

17 - COMMUNION WITH GOD (1) 18 - COMMUNION WITH GOD (2)

18 - COMMUNION WITH GOD (2) 19 - TEMPTATIONS MUST BE PUT AWAY

19 - TEMPTATIONS MUST BE PUT AWAY 20 - DESIGN OR INTENTION CONSTITUTES CHARACTER

20 - DESIGN OR INTENTION CONSTITUTES CHARACTER 21 - CONFESSION OF FAULTS

21 - CONFESSION OF FAULTS 22 - WEAKNESS OF HEART

22 - WEAKNESS OF HEART 23 - A SINGLE AND AN EVIL EYE

23 - A SINGLE AND AN EVIL EYE 24 - SALVATION ALWAYS CONDITIONAL

24 - SALVATION ALWAYS CONDITIONAL 25 - SUBMISSION TO GOD (1)

25 - SUBMISSION TO GOD (1) 25 - SUBMISSION TO GOD (2)

25 - SUBMISSION TO GOD (2) 26 - LOVE WORKETH NO ILL

26 - LOVE WORKETH NO ILL 27 - SELF-DENIAL

27 - SELF-DENIAL 28 - THE TRUE SERVICE OF GOD

28 - THE TRUE SERVICE OF GOD 29 - ENTIRE CONSECRATION A CONDITION OF DISCIPLESHIP

29 - ENTIRE CONSECRATION A CONDITION OF DISCIPLESHIP 30 - A SEARED CONSCIENCE (1)

30 - A SEARED CONSCIENCE (1) 30 - A SEARED CONSCIENCE (2)

30 - A SEARED CONSCIENCE (2) 31 - CONDITIONS OF BEING KEPT

31 - CONDITIONS OF BEING KEPT 32 - DAY OF THE NATIONAL FAST

32 - DAY OF THE NATIONAL FAST 33 - MEDIATORSHIP OF CHRIST

33 - MEDIATORSHIP OF CHRIST 34 - RESPONSE TO OBJECTIONS (1)

34 - RESPONSE TO OBJECTIONS (1) 35 - RESPONSE TO OBJECTIONS (2)

35 - RESPONSE TO OBJECTIONS (2) 36 - RESPONSE TO OBJECTIONS (3)

36 - RESPONSE TO OBJECTIONS (3) 37 - RESPONSE TO OBJECTIONS (4)

37 - RESPONSE TO OBJECTIONS (4) 38 - RESPONSE TO OBJECTIONS (5)

38 - RESPONSE TO OBJECTIONS (5) 39 - RESPONSE TO OBJECTIONS (6)

39 - RESPONSE TO OBJECTIONS (6) 40 - RESPONSE TO OBJECTIONS (7)

40 - RESPONSE TO OBJECTIONS (7) 41 - RESPONSE TO OBJECTIONS (8)

41 - RESPONSE TO OBJECTIONS (8) 42 - RESPONSE TO OBJECTIONS (9)

42 - RESPONSE TO OBJECTIONS (9) 43 - RESPONSE TO OBJECTIONS (10)

43 - RESPONSE TO OBJECTIONS (10) 44 - RESPONSE TO OBJECTIONS (11)

44 - RESPONSE TO OBJECTIONS (11) 45 - RESPONSE TO OBJECTIONS (12)

45 - RESPONSE TO OBJECTIONS (12) 46 - RESPONSE TO OBJECTIONS (13)

46 - RESPONSE TO OBJECTIONS (13) 47 - CHARGE ON ORDINATION

47 - CHARGE ON ORDINATION TO PROFESSING EDITORS OF PERIODICALS

TO PROFESSING EDITORS OF PERIODICALS TO PROFESSORS EX-MEMBERS OF THE CHURCH

TO PROFESSORS EX-MEMBERS OF THE CHURCH LETTERS TO MINISTERS (1)

LETTERS TO MINISTERS (1) LETTERS TO MINISTERS (2)

LETTERS TO MINISTERS (2) LETTERS TO MINISTERS (3)

LETTERS TO MINISTERS (3) LETTERS TO MINISTERS (4)

LETTERS TO MINISTERS (4) LETTERS TO MINISTERS (5)

LETTERS TO MINISTERS (5) LETTERS TO MINISTERS (6)

LETTERS TO MINISTERS (6) LETTERS TO MINISTERS (7)

LETTERS TO MINISTERS (7) LETTERS TO MINISTERS (8)

LETTERS TO MINISTERS (8) LETTERS TO MINISTERS (9)

LETTERS TO MINISTERS (9) LETTERS TO PARENTS (1)

LETTERS TO PARENTS (1) LETTERS TO PARENTS (2)

LETTERS TO PARENTS (2) LETTERS TO PARENTS (3)

LETTERS TO PARENTS (3) LETTERS TO PARENTS (4)

LETTERS TO PARENTS (4) LETTERS TO PARENTS (5)

LETTERS TO PARENTS (5) LETTERS TO PARENTS (6)

LETTERS TO PARENTS (6) LETTERS TO PARENTS (7)

LETTERS TO PARENTS (7) LETTERS TO BELIEVERS ON SANCTIFICATION (1)

LETTERS TO BELIEVERS ON SANCTIFICATION (1) LETTERS TO BELIEVERS ON SANCTIFICATION (2)

LETTERS TO BELIEVERS ON SANCTIFICATION (2) LETTERS TO BELIEVERS ON SANCTIFICATION (3)

LETTERS TO BELIEVERS ON SANCTIFICATION (3) LETTERS TO BELIEVERS ON SANCTIFICATION (4)

LETTERS TO BELIEVERS ON SANCTIFICATION (4) PREFACE

PREFACE 1 - LECTURE 1

1 - LECTURE 1 2 - LECTURE 2

2 - LECTURE 2 3 - LECTURE 3

3 - LECTURE 3 4 - LECTURE 4

4 - LECTURE 4 5 - LECTURE 5

5 - LECTURE 5 6 - LECTURE 6

6 - LECTURE 6 7 - LECTURE 7

7 - LECTURE 7 8 - LECTURE 8

8 - LECTURE 8 9 - LECTURE 9

9 - LECTURE 9 10 - LECTURE 10

10 - LECTURE 10 11 - LECTURE 11

11 - LECTURE 11 12 - LECTURE 12

12 - LECTURE 12 13 - LECTURE 13

13 - LECTURE 13 14 - LECTURE 14

14 - LECTURE 14 15 - LECTURE 15

15 - LECTURE 15 16 - LECTURE 16

16 - LECTURE 16 17 - LECTURE 17

17 - LECTURE 17 18 - LECTURE 18

18 - LECTURE 18 19 - LECTURE 19

19 - LECTURE 19 20- LECTURE 20

20- LECTURE 20 21 - LECTURE 21

21 - LECTURE 21 22 - LECTURE 22

22 - LECTURE 22 23 - LECTURE 23

23 - LECTURE 23 24 - LECTURE 24

24 - LECTURE 24 25 - LECTURE 25

25 - LECTURE 25 26 - LECTURE 26

26 - LECTURE 26 27 - LECTURE 27

27 - LECTURE 27 28 - LECTURE 28

28 - LECTURE 28 29 - LECTURE 29

29 - LECTURE 29 30 - LECTURE 30

30 - LECTURE 30 31 - LECTURE 31

31 - LECTURE 31 32 - LECTURE 32

32 - LECTURE 32 33 - LECTURE 33

33 - LECTURE 33 34 - LECTURE 34

34 - LECTURE 34 35 - LECTURE 35

35 - LECTURE 35 36 - LECTURE 36

36 - LECTURE 36 37 - LECTURE 37

37 - LECTURE 37 38 - LECTURE 38

38 - LECTURE 38 39 - LECTURE 39

39 - LECTURE 39 40 - LECTURE 40

40 - LECTURE 40 41 - LECTURE 41

41 - LECTURE 41 42 - LECTURE 42

42 - LECTURE 42 1 - PROVE ALL THINGS

1 - PROVE ALL THINGS 2 - NATURE OF TRUE VIRTUE

2 - NATURE OF TRUE VIRTUE 3 - SELFISHNESS

3 - SELFISHNESS 4 - THE TEST OF CHRISTIAN CHARACTER

4 - THE TEST OF CHRISTIAN CHARACTER 5 - CHRISTIAN WARFARE

5 - CHRISTIAN WARFARE 6 - PUTTING ON CHRIST

6 - PUTTING ON CHRIST 7 - WAY TO BE HOLY

7 - WAY TO BE HOLY 8 - ATTAINMENTS CHRISTIANS MAY REASONABLY EXPECT

8 - ATTAINMENTS CHRISTIANS MAY REASONABLY EXPECT 9 - NECESSITY AND NATURE OF DIVINE TEACHING

9 - NECESSITY AND NATURE OF DIVINE TEACHING 10 - FULNESS THERE IS IN CHRIST

10 - FULNESS THERE IS IN CHRIST 11 - JUSTIFICATION

11 - JUSTIFICATION 12 - UNBELIEF

12 - UNBELIEF 13 - GOSPEL LIBERTY

13 - GOSPEL LIBERTY 14 - JOY IN GOD

14 - JOY IN GOD 15 - THE BENEVOLENCE OF GOD

15 - THE BENEVOLENCE OF GOD 16 - REVELATION OF GOD'S GLORY

16 - REVELATION OF GOD'S GLORY 1 - THE SIN OF FRETFULNESS

1 - THE SIN OF FRETFULNESS 2 - GOVERNING THE TONGUE

2 - GOVERNING THE TONGUE 3 - DEPENDENCE ON CHRIST

3 - DEPENDENCE ON CHRIST 4 - WEIGHTS AND BESETTING SINS

4 - WEIGHTS AND BESETTING SINS 5 - REJOICING IN BOASTINGS

5 - REJOICING IN BOASTINGS 6 - CHURCH BOUND TO CONVERT THE WORLD (1)

6 - CHURCH BOUND TO CONVERT THE WORLD (1) 7 - CHURCH BOUND TO CONVERT THE WORLD (2)

7 - CHURCH BOUND TO CONVERT THE WORLD (2) 8 - TRUSTING IN GOD'S MERCY

8 - TRUSTING IN GOD'S MERCY 9 - THE OLD MAN AND THE NEW

9 - THE OLD MAN AND THE NEW 10 - COMING UP THROUGH GREAT TRIBULATION

10 - COMING UP THROUGH GREAT TRIBULATION 11 - DELIGHTING IN THE LORD

11 - DELIGHTING IN THE LORD 12 - HAVING A GOOD CONSCIENCE

12 - HAVING A GOOD CONSCIENCE 13 - RELATIONS OF CHRIST TO THE BELIEVER

13 - RELATIONS OF CHRIST TO THE BELIEVER 14 - THE FOLLY OF REFUSING TO BE SAVED

14 - THE FOLLY OF REFUSING TO BE SAVED 33 - SEEKING THE KINGDOM OF GOD FIRST

33 - SEEKING THE KINGDOM OF GOD FIRST 33 - FAITH IN ITS RELATIONS TO THE LOVE OF GOD

33 - FAITH IN ITS RELATIONS TO THE LOVE OF GOD 33 - VICTORY OVER THE WORLD THROUGH FAITH

33 - VICTORY OVER THE WORLD THROUGH FAITH 1 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (1)

1 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (1) 2 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (2)

2 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (2) 3 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (3)

3 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (3) 4 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (4)

4 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (4) 5 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (5)

5 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (5) 6 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (6)

6 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (6) 7 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (7)

7 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (7) 8 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (8)

8 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (8) 9 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (9)

9 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (9) 10 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (10)

10 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (10) 11 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (11)

11 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (11) 12 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (12)

12 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (12) 13 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (13)

13 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (13) 14 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (14)

14 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (14) 15 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (15)

15 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (15) 16 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (16)

16 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (16) 17 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (17)

17 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (17) 18 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (18)

18 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (18) 19 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (19)

19 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (19) 20 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (20)

20 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (20) 21 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (21)

21 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (21) 22 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (22)

22 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (22) 23 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (23)

23 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (23) 24 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (24)

24 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (24) 25 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (25)

25 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (25) 26 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (26)

26 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (26) 27 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (27)

27 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (27) 28 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (28)

28 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (28) 29 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (29)

29 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (29) 30 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (30)

30 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (30) 31 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (31)

31 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (31) 32 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (32)

32 - LETTERS ON REVIVAL (32) 1 - NATURE OF IMPENITENCE AND MEASURE OF GUILT

1 - NATURE OF IMPENITENCE AND MEASURE OF GUILT 2 - RULE TO ESTIMATE THE GUILT OF SIN

2 - RULE TO ESTIMATE THE GUILT OF SIN 3 - ON DIVINE MANIFESTATIONS

3 - ON DIVINE MANIFESTATIONS 4 - ON THE LORD'S SUPPER

4 - ON THE LORD'S SUPPER 5 - FORFEITING BIRTH-RIGHT BLESSINGS

5 - FORFEITING BIRTH-RIGHT BLESSINGS 6 - AFFLICTIONS OF RIGHTEOUS AND WICKED CONTRASTED

6 - AFFLICTIONS OF RIGHTEOUS AND WICKED CONTRASTED 7 - ON BECOMING ACQUAINTED WITH GOD

7 - ON BECOMING ACQUAINTED WITH GOD 8 - GOD MANIFESTING HIMSELF TO MOSES

8 - GOD MANIFESTING HIMSELF TO MOSES 9 - COMING TO THE WATERS OF LIFE

9 - COMING TO THE WATERS OF LIFE 32 - BLESSEDNESS OF ENDURING TEMPTATION

32 - BLESSEDNESS OF ENDURING TEMPTATION 33 - QUENCHING THE SPIRIT

33 - QUENCHING THE SPIRIT 33 - RESPONSIBILITY OF HEARING THE GOSPEL

33 - RESPONSIBILITY OF HEARING THE GOSPEL 33 - LETTERS TO CHRISTIANS

33 - LETTERS TO CHRISTIANS 1 - ALL THINGS FOR GOOD TO THOSE THAT LOVE GOD

1 - ALL THINGS FOR GOOD TO THOSE THAT LOVE GOD 2 - ALL EVENTS, RUINOUS TO THE SINNER

2 - ALL EVENTS, RUINOUS TO THE SINNER 3 - HEART-CONDEMNATION, PROOF THAT GOD CONDEMNS

3 - HEART-CONDEMNATION, PROOF THAT GOD CONDEMNS 4 - AN APPROVING HEART--CONFIDENCE IN PRAYER

4 - AN APPROVING HEART--CONFIDENCE IN PRAYER 5 - CONDITIONS OF PREVAILING PRAYER (1)

5 - CONDITIONS OF PREVAILING PRAYER (1) 5 - CONDITIONS OF PREVAILING PRAYER (2)

5 - CONDITIONS OF PREVAILING PRAYER (2) 5 - CONDITIONS OF PREVAILING PRAYER (3)

5 - CONDITIONS OF PREVAILING PRAYER (3) 6 - LETTERS TO CHRISTIANS (1)

6 - LETTERS TO CHRISTIANS (1) 6 - LETTERS TO CHRISTIANS (2)

6 - LETTERS TO CHRISTIANS (2) 7 - VIEWS OF JUSTIFICATION BY FAITH IN CHRIST

7 - VIEWS OF JUSTIFICATION BY FAITH IN CHRIST 1 - REGENERATION

1 - REGENERATION 2 - PLEASING GOD

2 - PLEASING GOD 3 - HEART SEARCHING

3 - HEART SEARCHING 4 - ACCEPTABLE PRAYER

4 - ACCEPTABLE PRAYER 5 - THE KINGDOM OF GOD UPON EARTH

5 - THE KINGDOM OF GOD UPON EARTH 6 - REWARD OF FERVENT PRAYER

6 - REWARD OF FERVENT PRAYER 7 - THE PROMISES OF GOD

7 - THE PROMISES OF GOD 8 - CHRIST THE MEDIATOR

8 - CHRIST THE MEDIATOR 9 - CHRIST MAGNIFYING THE LAW

9 - CHRIST MAGNIFYING THE LAW 10 - SPIRITUAL CLAIMS OF LONDON

10 - SPIRITUAL CLAIMS OF LONDON 11 - CONDITIONS OF PREVAILING PRAYER

11 - CONDITIONS OF PREVAILING PRAYER 12 - HOW TO PREVAIL WITH GOD

12 - HOW TO PREVAIL WITH GOD 13 - THE USE AND PREVALENCE OF CHRIST'S NAME

13 - THE USE AND PREVALENCE OF CHRIST'S NAME 14 - MAKING GOD A LIAR

14 - MAKING GOD A LIAR 15 - THE GREAT BUSINESS OF LIFE

15 - THE GREAT BUSINESS OF LIFE 16 - MOCKING GOD

16 - MOCKING GOD 17 - WHY LONDON IS NOT CONVERTED

17 - WHY LONDON IS NOT CONVERTED 18 - HOLINESS ESSENTIAL TO SALVATION

18 - HOLINESS ESSENTIAL TO SALVATION 19 - REAL RELIGION

19 - REAL RELIGION 20 - WHAT HINDERS CONVERSION of GREAT CITIES?

20 - WHAT HINDERS CONVERSION of GREAT CITIES? 21 - PROVING GOD

21 - PROVING GOD 22 - TOTAL ABSTINENCE A CHRISTIAN DUTY

22 - TOTAL ABSTINENCE A CHRISTIAN DUTY 23 - QUENCHING THE SPIRIT

23 - QUENCHING THE SPIRIT 24 - THE SABBATH-SCHOOL - CO-OPERATION WITH GOD

24 - THE SABBATH-SCHOOL - CO-OPERATION WITH GOD 25 - SABBATH-SCHOOL-CONDITIONS OF SUCCESS

25 - SABBATH-SCHOOL-CONDITIONS OF SUCCESS 26 - NOT FAR FROM THE KINGDOM OF GOD

26 - NOT FAR FROM THE KINGDOM OF GOD 27 - THE CHRISTIAN'S RULE OF LIFE

27 - THE CHRISTIAN'S RULE OF LIFE 28 - HARDENING THE HEART

28 - HARDENING THE HEART 29 - SEEKING HONOUR FROM MEN