Goforth of China

By Rosalind Goforth

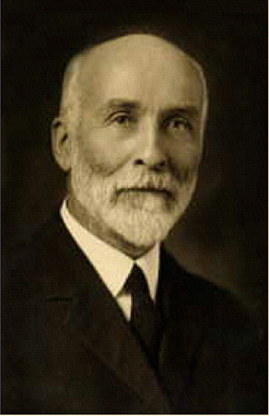

This work on Jonathan Goforth, written by his wife, Rosalind, covers the entire life of this passionate evangelist who was privileged to experience authentic revival during his missionary work in China.

Sometime in 1904 Jonathan received a copy of Charles Finney's ‘Lectures on Revivals.’ He became convinced that there were laws which, if practiced, would bring spiritual awakening. Stories of the Welsh revival added fuel to his inner fire and spurred him on to study Biblical and historic revivals.

In 1907 the dam burst.

After witnessing a genuine revival in Korea he took the message of revival to Manchurian mission stations. It was here that revival signs of deep conviction and repentance began to accompany his ministry. This is a thrilling story of one of China’s principal evangelists.

We have included 6 of the 28 chapters.

Chapter I

Early Leadings

Even a child is known by his doings. PROVERBS 20:11

IT IS the sincere desire of the writer of these memoirs that they be both written and read with the lesson of Jonathan Goforth’s favorite story in mind. The story is as follows: While the Goforth’s were attending a summer conference, south of Chicago, it was announced that a brilliant speaker was to come on a certain day for just one address. A very large expectant audience awaited him. The chairman introduced the speaker with such fulsome praise there seemed no room for the glory of God in what was to follow. The stranger had been sitting with bowed head and face hidden. As he stepped forward he stood a moment as if in prayer, then said:

Friends, when I listen to such words as we have just been hearing I have to remind myself of the wood-pecker story: A certain woodpecker flew up to the top of a high pine tree and gave three hard pecks on the side of the tree as woodpeckers are wont to do. At that instant a bolt of lightning struck the tree leaving it on the ground, a heap of splinters. The woodpecker had flown to a tree near by where it clung in terror and amazement at what had taken place. There it hung expecting more to follow, but as all remained quiet it began to chuckle to itself saying, Well, well, well! who would have imagined that just three pecks of my beak could have such power as that!

When the laughter this story caused ceased the speaker went on, Yes, friends, I too laughed when I first heard this story. But remember, if you or I take glory to ourselves which belongs only to Almighty God, we are not only as foolish as this woodpecker, but we commit a very grievous sin for the LORD hath said, My glory will I not give to another.

Many times Jonathan Goforth on returning from a meeting would greet his wife with, Well I’ve had to remind myself of the woodpecker tonight, or, I’ve needed half a dozen woodpeckers to keep me in place. Early in life he chose as his motto, “Not by might nor by power, but by my spirit” (Zech. 4:6). It was remarked that of the many wonderful tributes paid to the memory of Jonathan Goforth at that last triumphant service following his translation, there was not one but could be traced back to the abounding grace of God in him.

Dr. Andrew Bonar wrote of Murray MCheyne, All who knew him not only saw in him a burning and a shining light but felt also the breathing of the hidden life of God; and there is no narrative that can fully express this peculiarity of the living man. These words might truly have been written of Jonathan Goforth. He was God’s radiant servant always. Of all the messages which reached his wife after he had entered the gloryland, none touched her as the following:

A poor Roman Catholic servant girl in the home where the Goforth’s had often visited, on hearing of his passing said to her master, When Dr. Goforth has been here I have often watched his face and have wondered if God looked like him! That dear girl saw in his face, sightless though he was, what she hoped for in her Heavenly Father!

John Goforth came to western Ontario, Canada, from Yorkshire, England, as one of the early pioneers in 1840. His wife was dead. He brought with him his three sons, John, Simeon, and Francis. Francis married a young woman, named Jane Bates, from the north of Ireland. They settled on a farm near London, Ontario. Of their family of ten boys and one girl, Jonathan was the seventh child. He was bom on his father’s farm, near Thorndale, February 10, 1859.

Those were hard, grinding times for both father and mother, and for the boys, as one by one they were able to help by working out at odd jobs with neighboring farmers. There are those still living who remember how the Goforth boys were diligent, hard working lads. The hardships endured by the Goforth family, and indeed other pioneers of those early years, may be glimpsed by the following told in later years by Jonathan himself: I remember my father telling of his having tramped through the bush all the way from Hamilton to our home near London, a distance of seventy miles, with a sack of flour on his back.

When Jonathan was but five years of age, he had a miraculous escape from death. We quote from his diary:

My uncle was driving a load of grain to market. I was to be taken to my father’s farm some miles distant. The bags were piled high on the wagon, and a place was made for me just behind my uncle in a hole which was deemed perfectly safe. Suddenly, while driving down a hill, a front wheel sank deep into a rut, causing the wagon to lurch to one side. I was thrown out of my hole and started to slide down. Before my uncle could reach me I had dropped between the front and back wheels. The back wheel had just reached me, and I felt it crushing against my hip. At that same instant my uncle also reached me, but I was so pinned under the wheel he had difficulty in getting me free. A fraction of an inch farther and my hip would have been crushed.

The above was but the first of many remarkable deliverances from imminent death in Jonathan Goforth’s life. In writing of those early years he says:

My mother was careful in the early years to teach us the Scriptures, and to pray with us. One thing I look back to as a great blessing in my later life, was mother’s habit of getting me to read the Psalms to her. I was only five years of age when I began this but could read easily. From reading the Psalms aloud came the desire to memorize the Scriptures which I continued to do with great profit. There were times when I could not find anyone with time or patience to hear me recite all I had memorized.

From those earliest years I wanted to be a Christian. When I was seven years of age a lady gave me a fine Bible with brass clasps and marginal references. This was another impetus to search the Scriptures. One Sunday, when ten years old, I was attending church with my mother. It was Communion Sunday, and while she was partaking of the Lord’s Supper, I sat alone on one of the side seats. Suddenly it came over me with great force that if God called me away I would not go to heaven. How I wanted to be a Christian! I am sure if someone had spoken to me about my soul’s salvation I would have yielded my heart to Christ then.

For almost ten school years Jonathan was under the great handicap of being obliged to work on the farm, from April till October or even November. We are told, however, though naturally behind his schoolmates when returning to school in the autumn, by spring he could compete with the brightest.

The following striking picture of Jonathan as a schoolboy comes from the pen of Dr. Andrew Vining, a Canadian Baptist leader and one of Jonathan’s early schoolmates:

I remember Jonathan as cheerful, modest, courageous and honest, and I recall his constant sense of fairness, because my friendship with him began one day when he challenged and very effectively trounced a schoolhouse bully who had been making life unhappy for me, a younger and smaller boy. The years of his matchless service have given significance to one clear recollection I have of him. He had a habit of standing during recess in front of the maps which hung in the schoolroom. I clearly remember seeing him, day after day, studying these maps: the World, Asia, Africa. Many times since I have wondered if even as a boy there stirred within him a realization that his work was to he in faraway places of the earth.

His father put Jonathan at the age of fifteen in charge of their second farm, called The Thamesford Farm, some twenty miles distant from the home farm. His younger brother Joseph was to assist him. Of this responsible commission for a lad of his age, Jonathan wrote:

I was ambitious to run my farm scientifically, and I was well rewarded for my pains for my butter always sold for the highest price in the London market. In farming and cultivating I consistently endeavoured to apply scientific methods and with gratifying results. In handing over the farm, Father had called special attention to one very large field which had become choked with weeds. Father said, Get that field clear and ready for seeding. At harvest time I’ll return and inspect.

Jonathan, in later years, kept many an audience spellbound as he described the labour he put into that field. Ploughing and re-ploughing, the sunning of the deadly roots and again the ploughing till the whole field was ready for seeding; then how he procured the very best seed for sowing, and finally, he would tell of that summer morning, when just at harvest time, his father arrived, and how his heart thrilled with joy as he led his father to a high place from which the whole field of beautiful waving grain could be seen. He spoke not a word — only waited for the coveted well done. His father stood for several moments silently examining the field for a sign of a weed but there was none. Turning to his son he just smiled. That smile was all the reward I wanted, Goforth would say. I knew my father was pleased. So will it be if we are faithful to the trust our Heavenly Father gives us.

About this time an incident occurred which might well have ended fatally for the young lad. He was assisting at a neighbour’s barn-raising, an affair sufficiently dangerous, at that time, to keep the women folk in suspense till all was over. Operations had reached the dangerous point when the heavy beams had one by one been hauled up and laid on the cross bent. Jonathan was standing below these beams in the centre of the barn when a sudden cry rang out, Take care, the bent is giving! Looking up, he saw the beams had already started downward. There was no time to escape by running. There was but one thing to do — stand still and watch the beams as they fell and dodge between two. This he did, escaping unhurt.

While on the Thamesford Farm he became ambitious to study law and become a politician. After the evening chores were done he would walk miles to attend a political meeting. At the back of the home was a swamp. Here he would get out alone and practice speaking. Travelers on the highway some distance away could hear the voice. Being well versed on both sides of political situations, he was often the centre of heated discussions both at school and at home. Mother would often say I should be a teacher, he has said, but I argued the country needed good politicians!

Jonathan Goforth was now getting well on in his eighteenth year. He was known as a good lad, diligent, always ready to help others, eager to get an education (though this seemed, at times, hopeless), and he was liked by all for his happy, friendly ways — but he was still an un-awakened soul.

After taking a short commercial course in London, Ontario, Goforth returned to the old country school near his home, hoping to struggle through his high school there. The Rev. Lachlan Cameron, Presbyterian minister at Thamesford, visited the school regularly, holding Bible-study services with the pupils. Mr. Cameron was a godly man, of strong convictions, tireless energy, and deeply concerned about the salvation of his flock.

Jonathan’s marked proficiency in art penmanship, much in vogue at that time, attracted Mr. Cameron’s attention. The lad, always responsive to kindness, took a great liking for the minister and determined to hear him in his own pulpit. One who was present at that first Sunday gives the following:

Almost sixty years have passed since then but I can still see the young stranger sitting immediately in front of the minister with an eager, glowing look on his face and listening with great intentness to every word of the sermon.

It was Mr. Cameron’s unvarying custom to close each sermon with a direct appeal for decisions. We give in Jonathan’s own words what took place the third Sunday under Mr. Cameron:

That Sunday, Mr. Cameron seemed to look right at me as he pled, during his sermon, for all who had not, to accept the Lord Jesus Christ. His words cut me deeply and I said to myself, I must decide before he is through. But contrary to his usual custom, he suddenly stopped and began to pray. During the prayer the devil whispered, Put off your decision for another week. Then immediately after the prayer, Mr. Cameron leaned over the pulpit and with great intensity and fervour again pled for decisions. As I sat there, without any outward sign except to simply bow my head, I yielded myself up to Christ.

How complete was that yielding can be seen by his after life, and also from the following dictated to a daughter on his seventy-fifth birthday:

My conversion at eighteen was simple but so complete that ever onward I could say with Paul, I am crucified with Christ; nevertheless I live; yet not I but Christ liveth in me; and the life which I now live in the flesh I live by the faith of the Son of God who loved me and gave Himself for me (Gal. 2:20). Henceforth my life belonged to Him who had given His life for me.

At the next Communion, Jonathan joined the church and at once began to seek avenues of service for his newfound Master. He was given a Sunday-school class but this did not satisfy him. He sent off for tracts and became an object of wonder to the staid old elders, something akin to bewilderment to others, and amusement to the young, as he stood Sunday after Sunday at the church door giving to each one a tract! Very soon he started a Sunday evening service in the old schoolhouse a mile or more from his home.

We give in his own words two incidents of this time:

At the time of my conversion I was living with my brother Will. Our parents came on a visit, and stayed a month or so. For some time I felt the Lord would have me lead family worship. So one night I said, We will have worship tonight, so please don’t scatter after supper. I was afraid of what my father would say for we had not been accustomed to saying grace before meals much less having family worship.

I read a chapter in Isaiah and after a few comments we all knelt in prayer. Much to my relief, father never said a word. Family worship continued as long as I was home. Some months later my father took a stand for Jesus Christ.

The following occurred while he was attending high school in Ingersoll, twelve miles from the home farm:

My teacher was an ardent follower of Tom Paine. He persuaded all the boys in our class to his way of thinking. The jeers and arguments of my classmates proved too much for me. Suddenly all the foundations slipped. I was confounded! Instead of going to my minister or any other human aid, I felt constrained to take the Word of God alone as my guide. Night and day for a considerable period of time, I did little else than search the Scriptures until, finally, I was so solidly grounded I have never had a shadow of a doubt since. All my classmates, as well as our teacher, were brought back from infidelity, the teacher becoming one of my lifelong friends.

Thus the Lord began to use him from the time of his conversion. But for one year he still retained his ambition of becoming a lawyer and a good politician, believing he could serve the Lord thus. His Master, however, had other plans for this servant of His.

One Saturday afternoon Jonathan had occasion to go with horse and buggy to see his brother Will, whose farm lay some fifteen miles distant. He remained over night, and early Sunday morning started homeward. As he was leaving, Will Goforth’s father-in-law, Mr. Bennett, a saintly old Scot, handed Jonathan a well-worn copy of The Memoirs of Robert Murray MCheyne, saying, Read this, my boy, it’ll do you good. Laying the book on the seat beside him the young man drove off.

The day was one of those balmy, Indian Summer days in October. Jonathan had not gone far when remembering the book he opened it and began to read as he drove slowly on. From the first page the message of the book gripped him. Coming to a clump of trees by the roadside, he stopped the horse, and tethering it to a tree made a comfortable seat of dried leaves and gave himself up to the Memoirs. Hour after hour passed unnoticed, so great was his absorption in what he was reading. Not till the shadows had lengthened did he awake to how time had passed. He rose and continued his journey, but in those quiet hours by the roadside, Jonathan Goforth had caught the vision and had made the decision which changed the whole course of his life.

The thrilling story of MCheyne’s spiritual struggles and victories, and his life-sacrifices for the salvation of God’s chosen people, the Jews, sank deep into his very soul. All the petty, selfish ambitions in which he had indulged vanished for ever, and in their place came the solemn and definite resolve to give his life to the ministry, which to him meant the sacred, holy calling of leading unsaved souls to his Saviour.

That good man, Rev. Lachlan Cameron, greatly rejoiced on hearing of Jonathan’s decision. At once arrangements were made for the young man to come regularly to the Manse for lessons in Latin and Greek in preparation for his entering Knox College. I have before me a list of the books which Goforth says himself he devoured at that time. Here it is: Spurgeon’s Lectures to His Students; Spurgeon’s Best Sermons; Boston’s Fourfold State; Baxter’s Call to the Unconverted; Bunyan’s Grace A bounding, and Baxter’s Saints Rest.

The Bible was, however, even then, the great Book with him for he has left this record that for two years previously to his entering Knox College, Toronto, he rose two hours earlier each morning in order to get time for unbroken Bible study, before getting to work or off to school.

The story of Jonathan Goforth’s call to foreign service we now give in his own words:

Although I was clearly led to be a minister of the gospel, I rejected all thought of being a foreign missionary. All my thoughts and plans were for work in Canada. While attending high school in Ingersoll, studying Greek and Latin especially with a view to entering Knox College, I heard that Dr. G. L. Mackay, of Formosa, was to speak in Knox Church, Ingersoll. A schoolmate persuaded me to go with him to the meeting. Dr. Mackay, in his vivid manner, pressed home the needs and claims of Formosa upon us. Among other things, he said, For two years I have been going up and down Canada trying to persuade some young man to come over to Formosa and help me, but in vain. It seems that no one has caught the vision. I am therefore going back alone. It will not be long before my bones will be lying on some Formosan hillside. To me the heartbreak is that no young man has heard the call to come and carry on the work that I have begun.

As I listened to these words, I was overwhelmed with shame. Had the floor opened up and swallowed me out of sight, it would have been a relief. There was I, bought with the precious blood of Jesus Christ, daring to dispose of my life as I pleased. I heard the Lord’s voice saying, Who will go for us and whom shall we send? And I answered, Here am I; send me. From that hour I became a foreign missionary. I eagerly read everything I could find on foreign missions and set to work to get others to catch the vision I had caught of the claims of the unreached, unevangelized millions on earth.

At last the time drew near for Jonathan Goforth to leave the old farm home for the new, untried city life at Knox College. His mother, noted among the neighbours for her fine needlecraft, worked far into the night putting her best effort on the finishing touches to shirt or collar for the dear boy who was to be the scholar of the family. Little did she dream how the cut of the clothes or the fineness of the stitches would be regarded later!

During the last days at home, Jonathan’s heart was thrilled as he thought how soon he was to live and work with other young men who, like himself, had given themselves to the most sacred, holy calling of winning men to Christ. He had visions on reaching Knox of prayer-meetings and Bible study-groups where, in company with kindred spirits, he could dig deeper into his beloved Bible. So his joyous, optimistic spirit had reached fever heat when he arrived in Toronto and entered Knox College.

Chapter II

Beginning at Jerusalem

When he found his own soul needed Jesus Christ, it became a passion with him to take Jesus Christ to every soul. SAID OF JONATHAN GOFORTH

ON ENTERING Knox College, Jonathan Goforth quite unconsciously carried upon him in an unmistakable manner, the then (over fifty years ago) city despised earmarks of the country — the farm. He was unconventional to a degree, and utterly unacquainted with city habits and ways.

He had been but a very few days in his new environment when he became keenly conscious that his home-made garments would not pass muster in the college. He was very poor, depending entirely on his own resources, for he would not look to his father for help. Probably with a desire to economize as much as possible, he bought a quantity of material, intending to take it to a city seamstress to make into a new outfit. But before he could do so, the students got wind of it. Late that night a number came into his room, secured their victim, then cutting a hole at one end of the material (which was white), they put his head through and forcing him out into the corridor, made him run the full length up and down through a barrage of hilarious students.

The reader will say, Just a harmless prank. Yes, perhaps so — let it pass at that. The story is included in this record because of the effect it had upon Jonathan Goforth’s character. That night he knelt with Bible before him and struggled through the greatest humiliation and the first great disappointment of his life. The dreams he had been indulging in but a few days before had vanished, and before him, for a time at least, lay a lone road. Henceforth he was to break an independent trail. It is not hard to see God’s hand in this, forcing him out as it did into an independence of action which so characterized his whole after life.

We feel deeply grateful for the following noble and illuminating letter of those early days at Knox from Dr. Charles W. Gordon, (Ralph Connor), a classmate of Jonathan Goforth’s. The letter speaks for itself.

Toronto, October 30, 1936.

MY DEAR MRS. GOFORTH:

Very recently came to me the tidings of your husband’s death. The news stirs in me many memories of my old and dear friend, Jonathan Goforth. It was during my college days, of course, that I first came to know him. He was then working in a downtown mission and many were the strange stories told by him. My first impression of him was that he was a queer chap — a good fellow — pious — an earnest Christian, but simple-minded and quite peculiar. I was then a student in the University of Toronto, and though a member of St. James Square Church, a regular attendant upon Dr. King’s ministry, and a member of his very fine Bible class. Yet Jonathan’s earnest devotion to his work — mission work down in the slums of St. Johns Ward — seemed to me as rather quaint. I was rather prominent in the athletic and literary circles of the college, and not personally or deeply interested in the saving of fallen women in St. Johns Ward. Theoretically? Yes! Personally? No. But to Jonathan Goforth, the denizens of St. Johns Ward were of those poor and brokenhearted to whom the young enthusiast of Nazareth felt Himself pledged.

Jonathan Goforth in his enthusiastic innocence, aroused the amusement of his table-mates at dinner with his naive stories of his experiences in the Ward. His labors carried him into strange surroundings. He was too innocent to recognize a harlot when he saw her, or too pitiful to avoid her. His dinner-table tales some times amused, at other times annoyed, his fellow students. His activities in the saving of the lost aroused in some a contempt for his simplicity. He became a subject for an Initiation Ceremony; hailed at midnight before his judges, students of Knox College, he was subjected, I learned, to indignities, and warmed against further breaches of good form by his tales of his experiences with sinners. Goforth was deeply hurt, not so much for himself, but that such a thing should happen in a Christian college. He felt that so grievous a thing should be reported. He went to Principal Caven. The wise old saint soothed his hurt feelings, treated the Initiation Ceremony as a silly prank of foolish boys, but took no official action. Jonathan, saddened and hurt, went on his way but learned his lesson that it avails little to ‘cast pearls before swine’.

The day came when honored by the whole body of students, he went forth to his mission to China, their representative supported by their contributions, and backed by their prayers, the first Canadian missionary to be supported in his work by his fellow-students, Twenty-five years later, in the great Missionary Convention in Massey Hall, gathered from all parts of Canada, cleric and lay, men and women, some thousands, acclaimed with grateful hearts, touched with the Divine fire that burned in the heart of their great champion among the hundred millions of Chinese, the services of Jonathan Goforth. The slogan of that meeting was China for Christ, in this generation. It was my privilege and honour to speak that night for China to that great assemblage of enthusiastic Presbyterians. I remember saying that night that it had taken twenty-five years to prove that Jonathan Goforth in his method and spirit as a missionary, was right, and that we who made light of him, were wrong.

The characteristic features of Goforth were the utter simplicity of his spirit, the selfless character of his devotion, and the completeness of his faith in God. As I came to know him better, I came more and more to honour his manliness, his humility, his courage, his loyalty to his Lord, and his passion to save the lost. As I think of him today, my heart grows humble with the thought of his selfless devotion, and warm with love for him as one of my most honoured friends.

I know well that the grief and loneliness will be swallowed up in your humble pride in him, in your glad thankfulness for the grace of God in him that made him the great man, the great missionary, the great servant of Jesus Christ that he was.

Twenty-two, I think, were members of our graduating class; the great majority of them volunteered for service in the mission field at home or abroad. Not one of them, I am quite sure but would greatly love Jonathan Goforth and thank God for his influence on their characters and lives . . . . .

Very truly yours,

CHARLES W. GORDON (Ralph Connor)

We have glimpsed enough to understand something of what Jonathan Goforth went through during that first period at Knox. Suffice it now to add that without one exception, every student who had taken part in what had hurt and humiliated him during those early days at Knox, had, before he left the College, come to him expressing their regret.

On his very first day in Toronto, Jonathan Goforth walked down through the slum-ward, south of the college, praying that God would open the way for him to enter those needy homes with the gospel of Jesus Christ. The first Sunday morning was spent in visiting the Don jail, a practice he kept up throughout his whole college course. Until the warden came to know him, he was allowed only into the assembly hall. Then, when he had won the official’s confidence, he was given liberty to go into the corridors.

One Sunday morning, as he was standing in the centre of the corridor, about to begin his address, a man burst out in a bombastic manner - I don’t believe there is a God. There was tense silence for a moment.

Then Jonathan walked over to the man’s cell, and said in a very friendly way, Why, my good friend, this Book l have here speaks about you. The man laughed incredulously. What could any book have to say about him? Goforth turned up Psalm 14, and read the first verse: The fool hath said in his heart, There is no God. At that the whole corridor burst out laughing. Although he had intended to speak on another subject, he went ahead and spoke from the text just quoted. The men gave him close attention, and when he was through, all seemed to be under deep conviction and some were in tears. He then went from cell to cell, making a personal appeal to each man. Several came out definitely for Christ that morning.

For two years his work in the slums was in connection with the William Street Mission. Then he became city missionary for the Toronto Mission Union, a faith mission which guaranteed him no stated salary. His income therefore was very uncertain. Some-times he had not sufficient to buy even a postage stamp. The four years of Goforth’s life as city missionary of the Toronto Mission Union, gave him many opportunities to prove God’s faithfulness in answering prayer for temporal needs. We give just two definite instances along this line.

The first was when one Saturday morning, as the hour drew near to settle with the housekeeper for his board, Jonathan felt greatly troubled, for he was then two weeks behind and had nothing with which to meet this debt. He then prayed definitely that the Lord might undertake for him, for he felt that it was not right to be in debt to anyone. As he prayed, a call came for him to preach in a certain place out of the city. He was obliged to leave at once, as there was barely time to catch the train. That Sunday something over seventeen dollars was given him, over and above his expenses — to him, an unheard-of thing. So, on his return to Toronto, he was able to pay his board up to date, with sufficient money over to meet some very pressing needs.

The second instance was when graduation time drew near. Goforth began to feel the urgent need for a good suit. He again prayed very definitely for this. One day, while walking down Yonge Street, the head of a well-known tailoring establishment, Mr. Berkinshaw, was standing in front of his shop and on seeing Goforth, he hailed him with, Say, Goforth, you’re the very man I’m looking for! Come in. A black suit of the finest quality was brought out. Goforth expostulated, saying, I do need a suit, but this is too much for my pocket. Mr. Berkinshaw, however, insisted upon his trying on the suit. It fitted perfectly. Now, said the tailor, are you too proud to accept it as a gift? For it’s yours for the taking. A customer of mine had the suit made but it didn’t please him, so it was left on my hands. Then Jonathan told him of his felt need and prayer for a suit. The blessing that followed was twofold — to the giver, that God had used him as His channel — and to the receiver, the strengthening of faith for this fresh token of God’s faithfulness in answering prayer.

On each furlough, Goforth always dealt with that firm as a debt of honour. Fifty years later, one of the first letters to reach Mrs. Goforth after her husband’s translation, was the following from Mr. Collier, the then head of the same firm.

One of God’s gentlemen has gone home to his reward and what a reward it must be! If ever a Christian gentleman trod this earth, Dr. Goforth was one of the best.

His religion and his love for helping others shone in his face!

His true and simple faith in God was passed on to others. As his Master, he went about doing good. Jonathan Goforth is dead so far as this world is concerned, but he is not dead, his spirit lives on not only in the better world but in the lives of those whom he has touched here. We will never know how far-reaching his ministry has gone — it will go on and on, forever. You have lost a loving husband and father and I and others have lost a wonderful friend. I loved to have him come in and always felt that I had met a good man who influenced my life.

As I write, an interesting word-picture of those student days at Knox College comes from an old elder in Toronto who, for many years, has been Jonathan Goforth’s prayer-helper:

On one occasion, Goforth was scheduled to speak at a certain place on Sunday. When about to leave for the station he found he had only sufficient money to buy a ticket one station short of where he was to speak. At once he decided to get his ticket to that station and walk the rest of the way, a distance of ten miles. This he did. When about eight miles of his foot journey had been covered he came upon a group of road-menders sitting by the roadside. Glad to rest he sat down among them. One offered him a pull from his whiskey flask! It was not long before he had the ears and hearts of his audience. On leaving he gave all a hearty invitation to his meeting the following day. To his great joy several of the men turned up. And at least one of these men decided for Christ that day.

Of Sunday-school work in the slums, Goforth writes:

Sunday-school was a nerve-racking ordeal for the mission workers. Try as he might, the superintendent simply could not keep order. When he started to pray some of the boys would begin pitching their caps around in all directions. Groans and mocking amens almost drowned out the superintendents voice. One of the worst offenders among the boys was a little stunted Roman Catholic lad, named Tim. One day Tim went over to a trough nearby and filled his mouth with dirty water. Creeping up behind me, he spued the contents of the water into the faces of the boys. In an instant the room was in an uproar, and only after great difficulty were the teachers able to get some kind of order again. And then Tim was in another part of the room, knocking the girls hats on the floor. He went thus from one thing to another keeping the school in almost continuous turmoil, For more than a year we could do nothing with him.

One winter afternoon, when the snow lay deep on the ground, I was walking along Queen Street when I spied Tim dragging a sleigh-full of coal across the streetcar tracks. Deep trenches had been dug in the snow to enable the cars to run on the tracks. Tim’s sleigh had got stuck in one of these trenches. A car was approaching and Tim, seeing it, tugged frantically this way and that, but to no avail. I ran forward to his assistance, and in a moment, the sleigh and Tim were safely out of the trench. He looked up into my face with a smile that spoke louder than words and in the next instant was gone. I never had any more trouble with Tim. He was on my side ever afterwards.

On weekdays, Jonathan spent much of his time visiting in the slum district. His strategy was to knock at a door, and when it opened a few inches, he would put his foot in the crack. He would then tell them his business and if, as was usually the case, they said they were not interested and went to close the door, his foot prevented the proceedings from being brought to an abrupt end. As he persisted, the people of the house almost invariably gave way and let him in. Of all the many hundreds of homes that he visited during his years of slum-work, there were only two where he definitely failed to gain an entrance.

While visiting in slum homes, Goforth would some times lead as many as three people to Christ in a single afternoon. Dr. Shearer, who accompanied him on his visits one day said, as they parted, Goforth, if only this personal contact could have been made with every human soul, the Gospel would have reached every soul long ago. He carried his message into all kinds of places, even brothels. He visited seventeen of these places on one street. It was his joy to be able to lead a number of the young women to Christ. Only once during all his years of work, among this class of people, did he meet with flippancy and contempt.

One night as he was corning out from a street that had a particularly evil reputation, a policeman, a friend of his, met him. How have you the courage to go into those places? he asked. We never go except in twos or threes. Well, I never go alone, either, Goforth answered. There is always Someone with me. I understand, said the policeman. He was a Christian.

Goforth was returning to the college late one other night, from some ministry in the slum ward, when he noticed a light in a basement window. Always keen, not only to take advantage of opportunities but to make them, he tried the door beside the window and finding it unlocked walked in to face a group of gamblers. One of them asked his name. Goforth, he replied. This so amused the men, they broke into hearty laughter. Cards were pushed aside and Jonathan was given a chance to preach Christ from his ever ready Bible.

At the beginning of a fall session at Knox College, Principal Caven asked Goforth how many families he had visited in Toronto that summer. Nine hundred and sixty, was the reply. Well, Goforth, said the Principal, if you don’t take any scholarships in Greek and Hebrew, at least there is one book that you’re going to be well up in, and that is the book of Canadian human nature.

The experience which he had had in the slums of Toronto proved invaluable to Jonathan Goforth in after years, for he found Chinese human nature very much the same as Canadian human nature.

Goforth’s first Home Mission field lay in the Muskoka district. He had four preaching points, Allensville, Port Sydney, Brunel, and Huntsville. The field was twenty-two miles long and twelve miles wide. He set out at once to visit every home in the whole area, regardless of denomination or creed, and this, so far as he knew, he succeeded in doing.

At Allensville, Port Sydney, and Brunel, Goforth’s work soon began to show most encouraging results. The little frame buildings in which the services were held became too small to hold the people, many of whom had to walk miles to get to church. The people would be crowded in everywhere, even on the pulpit steps. Once, in his excitement, he flung his hand back and hit several people behind him, thus causing convulsions in the audience. A number of people, notably Tom Howard, one of the most notorious characters in the countryside, were led to Christ. This man broke right down in the middle of a service and confessed his sins. When Goforth discovered Howard had a fine voice, he appointed him to lead the singing. He would almost raise the roof with his intensity, the tears streaming down his cheeks.

How to reach the boys of Huntsville was from the beginning a problem with the young missionary. He could not persuade them to come to church, though he asked them often enough. One afternoon as the boys were playing baseball on the common across the river from the church, Goforth joined them. After a while the profanity became so bad, he dropped his bat and excused himself from the game. The boys were thereupon most apologetic and promised they would not offend again, After the game, the boys accompanied Goforth to the church where they spent an hour studying the Bible together. This continued almost every evening throughout the summer.

On one occasion while following the trail through a thick bush, when turning a sharp bend in the path he came face to face with a great bear just to one side of the path. The bear rose, sat hack on its haunches, and stared. For brief moments, Goforth stood still and stared back at the bear. Then the thought came, I’m on my Masters business and He can keep me. Going steadily but slowly forward, he had to almost touch the bear to pass him but the great beast made no sign of moving. When some distance on, he looked back and saw the bear walking slowly off into the bush.

The following letter gives a very human picture of Goforth on his first mission held.

The year 1882 was a delight to the Presbyterians at Allensville. Father and mother, who were living in Huntsville, told me so much about the Spirit-filled young student they had, Mr. Jonathan Goforth. I was sitting with my baby on my knee one day when a young man came to the door and announced him-self as Jonathan Goforth, Presbyterian student for Huntsville and Allensville. I invited him in and we talked over many things. He told me he was walking from Aspidin to Huntsville, a distance of some ten miles, and calling at every house, reading the Word of God and offering prayer if no objection was made.

Mr. Goforth read and then prayed for the baby and me and I think I sometimes feel the influence of that prayer even yet. After leaving us, he went on his way, carrying his friendliness and God’s message to each home. . . . . All through the years, here and there, I have met with kind remembrances of these evangelistic ministries. . . . I know his influence is still abiding in the lonely places of that pleasant country. . . . . Oh, he came in the Spirit and power of the Holy Ghost.

Another writes of the same time, The evangelist, Goforth, was young and slightly built, attracting every-one by his gentle humility and intense earnestness and Christ-likeness. Mr. Alexander Proudfoot one of the Huntsville Church leaders reckoned that Goforth must have walked from sixteen to eighteen miles each Sunday, besides speaking three times.

Chapter III

“My Lord First”

That in ALL things He might have the pre-eminence. THE APOSTLE PAUL

IT SEEMS fitting, and as Jonathan Goforth himself would wish, that a loving tribute should here be paid to the memory of one whom he ever remembered and spoke of as his guardian angel of the early years.

In the old log schoolhouse of West Nissouri, and later, for seven years in the building which took its place, Charlotte McLeod, leader among the girls, and Jonathan Goforth, the recognized leader among the boys, attended school together. It was but natural that between these two there should come to be an abiding friendship, which, as the years passed, ripened into something deeper. Miss. McLeod was devoted to her church, the Baptist denomination, and always this, since Jonathan Goforth was a Presbyterian, seemed to her the One insurmountable banner that kept her from joining her life with his. Soon after the Goforth’s sailed for China, Charlotte McLeod sailed for India, where for twenty-eight years, she gave devoted and loving service among the Telegus. She died in India, remembered by the natives as the star-eyed missionary.

We come, now, to a very intimate story. The writer has pondered and prayed long before summoning the courage to give it, but many details later on in this record, can be better understood after knowing something of one, who for forty-nine years, was Jonathan Goforth’s closest companion and the mother of his eleven children.

I was born near Kensington Gardens, London, England, on May 6th, 1864, coming to Montreal, Canada, with my parents three years later. From my earliest childhood, much time was spent beside the easel of my artist father, who thought that I should be an artist. My education, apart from art, was received chiefly in private schools or from my own mother.

In May, I 1885, I graduated from the Toronto School of Art and began preparations to leave in the autumn for London to complete my art studies at the Kensington School of Art. I was an Episcopalian. Those of you who have read thus far may wonder how I could have been the one of God’s choice for such a man as Jonathan Goforth. The foregoing, however, is but half the picture. Here is the other side.

When twelve years of age, I heard Mr. Alfred Sandham speak at a revival meeting, on John 3 : 16. As he presented with great intensity and fervour, the picture of the love of God, I yielded myself absolutely to the Lord Jesus Christ and stood up among others, publicly confessing Him as my Master. On the way home from that meeting, I was told again and again how foolish it was for me to think I could possibly be sure that Christ had received me. So early the next morning, I got my Bible, given me by my godmother in England, and turning the pages over and over, I prayed that I might get some word which would assure me Christ had really received me. At last I came to John 6: 37, Him that cometh to me I will in no wise cast out. These words settled that difficulty for I saw clearly that this included all, even me.

Then another difficulty arose. I was told I was to young to be received, and again I went to my Bible and turned the pages to see if there was any message to meet that problem, and I came, after searching a long time to these words, Those that seek me early shall find me (Prov. 8: 17). On these two texts I took my stand and have never doubted since then that l was the Lord’s child.

From that time, and increasingly as the years passed, there seemed to be two elements contesting within me, one for art, the other — an intense longing to serve the Master to whom I had given myself.

In the early part of 1885, when still in my twentieth year, I began to pray that if the Lord wanted me to live the married life, he would lead to me one wholly given up to Him and to His service. I wanted no other. One Sunday in June, of that year, a stranger took the place of the Hon. S. H. Blake, our Bibleclass teacher. This stranger, Mr. Henry O’Brien, came to me about the hymns, as I was organist. Three days later, two large parties were crossing the lake on the same boat, one, an artists’ picnic, bound for the Niagara Falls, the other, bound for the Niagara-on-the-Lake Bible Conference. I was with the former group, but my heart was right with the others who were evidently having a wonderful time of spiritual conference. That evening, all returned on the same boat with the addition of a conference group who had crossed on the mid-day boat.

I was sitting in the artist circle, beside my brother, F. M. Bell-Smith, when Mr. Henry O’Brien touched me, saying, Why, you are my organist of Sunday last! You are the very one I want to join us in the Mission next Saturday. We are to have a Workers’ meeting and tea, and I would like you to meet them all. I was on the point of saying this was impossible, when my brother whispered, You have no time. You are going to England. Partly to show him I could do as I pleased — what a trifle can turn the course of a life — I said to Mr. O’Brien, Very well; expect me on Saturday.

As Mr. O’Brien turned to leave, he spied, and called to one who looked to me to be a very shabby fellow, whom he introduced as Jonathan Goforth, our City Missionary. I forgot the shabbiness of his clothes however, for the wonderful challenge in his eyes!

The following Saturday found me in the large, square, workers’ room of the Toronto Mission Union. Chairs were set all around the walls, but the centre was empty. Just as the meeting was about to begin Jonathan Goforth was called out. He had been sitting across the corner from me with several people between. As he rose, he placed his Bible on the chair. Then something happened which I could never explain, nor try to excuse. Suddenly, I felt literally impelled to step across, past four or five people, take up the Bible and return to my seat. Rapidly I turned the leaves and found the Book worn almost to shreds in parts and marked from cover to cover. Closing the Book, I quickly returned it to the chair, and returning to my seat, I tried to look very innocent. It had all happened within a few moments, but as I sat there, I said to my-self, That is the man I would like to marry!

That very day, I was chosen as one of a committee to open a new mission in the east end of Toronto, Jonathan Goforth being also on the same committee. In the weeks that followed, I had many opportunities to glimpse the greatness of the man which even a shabby exterior could not hide. So when, in that autumn he said, Will you join your life with mine for China? my answer was, Yes, without a moment’s hesitation. But a few days later when he said, Will you give me your promise that always you will allow me to put my Lord and His work first, even before you? I gave an inward gasp before replying, Yes, I will, always, for was not this the very kind of man I had prayed for? (Oh, kind Master, to hide from Thy servant what that promise would cost.)

A few days after my promise was given, the first test in keeping it came. I had been (woman-like) indulging in dreams of the beautiful engagement ring that was soon to be mine. Then Jonathan came to me and said, You will not mind, will you, if I do not get an engagement ring? He then went on to tell with great enthusiasm of the distributing of books and pamphlets on China from his room in Knox. Every cent was needed for this important work. As I listened and watched his glowing face, the visions I had indulged in of the beautiful engagement ring vanished. This was my first lesson in real values.

The two years given to work in the East End slums, was of the greatest possible value in gaining experience which gave me a realization of my own personal responsibility towards my unsaved sisters. Of course, by this time, art had practically dropped out of my life, and in its place had come a deep desire to be a worthy life-partner of one so wholly yielded to his Divine Master, as I knew Jonathan Goforth to be.

Chapter IV

The Vision Glorious

OBEDIENCE is the one qualification for FURTHER VISION.

G. CAMPBELL MORGAN

EVER SINCE the night in Ingersoll when George Leslie Mackay’s appeal for recruits for the foreign field touched him so deeply, Jonathan Goforth’s heart was on fire for foreign missions. He lost no opportunity to press home the claims of the unevangelized masses of the earth. He compelled a hearing by the intensity of his enthusiasm. The following incident will show what persuasiveness he had in pleading the cause that was so dear to his heart.

He was sent out one Sunday to fill a pulpit, and as usual, spoke on missions. On the Monday morning, as the train was pulling out of the station, a man asked if he might share his seat. I heard you preach on missions in our church yesterday, said this man. When I heard that you were coming to speak on missions, I prepared myself with five cents for the collection. I usually give coppers on Sunday, but seeing that this particular collection was to go for missions, I decided that I couldn’t think of giving less than five cents. Well, I went to church with my five cents. After you commenced speaking, I began to wish it were ten cents. A little later, and I thought a quarter too little. You were not half-way through till I wished I had a dollar bill, and by the time you finished, I would gladly have given a five-dollar bill.

Some months later, Goforth received a letter from this man’s pastor in which he said, I suppose you will remember having had a conversation with a certain member of my congregation on the train. Well, this man has since sold a piece of property of property and has given several hundred dollars of the proceeds to foreign missions.

The time came when Jonathan Goforth faced the problem of how he was to get to China, the field upon which his heart was set. His own church had no work in that country, and there seemed little prospect of her being induced to open a mission field there. So, although he would much have preferred to go out under own board, he began to look else where for an appointment. Dr. Randal, of the China Inland Mission, when passing through Canada in 1885, had given Goforth a copy of Hudson Taylor’s China’s Spiritual Need and Claims. The book made a profound impression upon him and awakened in him a deep regard for the great Mission of which Hudson Taylor was the founder, a regard which grew stronger with the years. It was only natural, therefore, since there seemed to be no possibility of an opening, as far as his own church was concerned, that he should approach the China Inland Mission. This he did, sending in his application to the headquarters of the Mission in London. Thus, Goforth was the first one on the American Continent to offer for the China Inland Mission, his friend, Alexander Saunders, being the second, sending as he did, his application some months later.

A month and more went by, and no answer came. (He found out, later, that his letter had gone astray). Nothing daunted, he wrote again. In a short time he received word that his application had been favourably received. In the meantime, however, his own fellow-students at Knox College learning of his plans, had started a movement which was to decide the question of the Board under which Goforth should work.

When Jonathanan Goforth first entered Knox College, brimming over with missionary enthusiasm and anxious to tell everyone about it, his fellow-students set him down as a crank. But this did not cool his ardour, and his enthusiasm proved contagious. Gradually there developed among the student body a remarkable interest in the cause of foreign missions.

The movement at Knox was coincident with a revival of missionary interest throughout a large part of the Christian world. At the East Northfield Conference in 1886, the Student Volunteer Movement was set in motion On the last day at Northfield one hundred young men and women announced their willingness to become missionaries. The movement spread in a truly amazing fashion through the universities and theological schools of the continent. President McCosh of Princeton said that not since Pentecost had there been such an offering of young lives.

At Knox and in other Canadian Colleges, daily prayer-meetings for missions were started. In the winter of 1886 - 87, among the students of Knox and Queen’s alone, there were thirty-three volunteers for the foreign field. It was the Knox students who, when they heard that Goforth had applied to the China Inland Mission, as his own church could not send him, decided to raise the necessary funds and start a mission in China with Jonathan Goforth as their missionary.

In order to ensure the success of the venture, it was felt necessary to secure the co-operation of the College Alumni. The matter was brought up at the annual meeting of the Alumni Association, in the fall of 1886. Many of the Alumni were strongly set against the scheme, arguing that the Presbyterian Church had too many fields already. It was also urged that her Home Mission work came first, and was all that she could handle. One man after another spoke with such telling force against the scheme, that its promoters feared the battle was lost. Then Jonathan Goforth was called upon. He spoke with unusual power as the result of the meeting indicated. For him the issue was crystal clear, and his ringing challenge went home to the hearts of ministers and students alike. He reminded them of Joshua going down to the rim of the swollen floods of Jordan in obedience to God’s command. He did not wait for a bridge to be thrown across, but went forward by faith and the way opened up. As soon as we are prepared to go forward and preach the Gospel at God’s command, he went on, then the Lord of the harvest will surely supply the need. When he had finished speaking the Alumni Association, without any further discussion, voted unanimously to support the venture.

Some years later, Jonathan Goforth when home on furlough, was speaking in a Presbyterian Church in Vancouver. The minister introducing him said:

This fellow took an overcoat from me once. It happened this way. I was going up to the Alumni meeting in Knox College, Toronto, determined to do everything in my power to frustrate the crazy scheme which the students of the college were talking about, i.e., starting a mission field of their own in Central China. I also felt that I needed a new overcoat; my old one was looking rather shabby. So I thought I would go to Toronto and kill two birds with one stone. I would help sidetrack the scheme and buy an overcoat. But this fellow here upset my plans completely. He swept me off my feet with an enthusiasm for missions which I had never experienced before, and my precious overcoat money went into the fund!

The Alumni of Knox College had been won over. The next step was to win the official sanction of the Church. Jonathan Goforth had already done not a little on his own account to turn the mind of the Church towards China. Not content with the opportunity which Sunday supply work afforded him, he bought hundreds of copies of Hudson Taylor’s China’s Spiritual Need and Claims, and other books on China, mailing them chiefly to ministers of the Church. The expense of this undertaking was at first shouldered by himself. (Money that might have gone for personal needs such as clothes, doubtless going into this work). Then, later, gifts came in which enabled him to carry it on. One who knew him at this time tells of frequently going to his room to help in the work of mailing out the books. In the room were piles of books and pamphlets on China ready to be sent out. Sometimes, three or four students were helping. A regular routine was observed, Goforth first reading aloud letters received containing donations for the work, many of these being small gifts from Sunday-school children who had heard him speak. Then all knelt in prayer for blessing on the books sent out, and thanksgiving for gifts received.

We cannot doubt but this work was an important agency in forwarding and feeding the remarkable tide of interest in foreign missions of this period and also That it paved the way for the visit of Dr. Hudson Taylor to Canada in 1888. Dr. Henry W. Frost, for many years Home Director of the China Inland Mission for Canada and the United States, writes the following striking tribute which will be read with deep interest, especially so by members and friends of that great Mission:

In the year 1885, I attended for the first time, the Believer’s Conference held at Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario. The spiritual pressure in the direction of foreign missions came in the year 1885 from the fact that there were present in the audience two persons whose lives were committed to foreign missions. These were Wm. E. Blackstone and Mr. Jonathan Goforth. The first friend was well known throughout the States and Canada as a great preacher and a notable advocate of the evangelization of the world, and the second was scarcely known at all, being but a student in Knox College, Toronto, yet recognized as one who was on fire in respect to work in the foreign field. A missionary afternoon was given to Mr. Blackstone and Mr. Goforth for addresses upon foreign missions. I was old enough to be in business at that time, and yet, I had never heard anyone speak on work amongst the heathen. It was largely curiosity, therefore, that took me to the afternoon meeting.

The first speaker was Mr. Wm. E. Blackstone, who gave us a pyrotechnic display, intellectually speaking, which was illuminating and thrilling and which left us exhilarated as touching divine possibilities. The second speaker was the unknown Jonathan Goforth. The first thing that I discovered about this young man was that he had the face of an angel, and the second thing was — I am tempted to say it — that he had the tongue of an arch-angel. Never had I been so stirred by an address. And, besides, the speaker was not content to depend alone upon his utterances; he had hung on every side back of the platform, charts which appealed to the eye and of these he spoke one by one and with great exactness.

The chart which impressed me most was the one in the centre, and which showed the religious condition of the world’s inhabitants. In the lower half of this chart, were nine hundred black squares representing the nine hundred millions of heathendom, in the midst of these black squares was a white dot which set forth the Christian Church in heathendom.

As Mr. Goforth described these black squares and this one tiny white dot, a great conviction took hold upon me. I felt that the church at home was guilty of a great crime, to leave these nine hundred millions of people in such midnight spiritual darkness when Christ was the light that lighteneth every man that cometh into the world. Sitting there, looking and listening, I cried in my inmost soul, O God, what can I — what shall I do? Mr. Goforth little knew what the Spirit was doing there that day in the soul of one of his hearers. It was not necessary that he should know. But it is a fact that he wrought with God in that meeting and that he left one of his hearers prostrate at the feet of Christ, surrendered unto Him for the fulfillment of His compassionate will toward those who knew Him not.

This was the beginning of my interest in foreign missions. It was not long afterwards that I offered to the China Inland Mission for service in China. I could not go; but God gave me a work to do for China while at home and out of it has come the China Inland Mission in North America. I am constrained to say, therefore, that Mr., afterwards Dr., Goforth, was the originator of what is now a large enterprise in behalf of the Christ-less Chinese, This then is another jewel in a crown which has many gems, all of which now sparkle in the glory which excelleth, to the praise of Christ our Lord.

The doctrine of the Lords pre-millennial return was much emphasized at those Niagara-on-the-Lake Conferences. Goforth came to accept fully this teaching which was also believed in by all his associates of the Toronto Mission Union. His belief in the possible return of Our Lord, at any time, was ever a most blessed and inspiring element in his religious life.

Of the children’s response to his message, Goforth himself wrote:

I spent a Sabbath talking on missions at a certain place. The Sunday-school boys and girls were greatly interested. How did I know? Well, when I got through speaking, a number of them came forward, some with pennies, some with five-cent pieces and even twenty-five cent pieces. But the interest didn’t end there, for next day as I was staying at the manse, they came in ones and twos and even in groups of eight or ten with their offerings for missions. On Monday forenoon, as I was going down the street, I met a crowd of sunny faces on the way to school and they said, We are going to China too when we grow big.

Among Jonathan Goforth’s papers we found the following story for children which will speak for itself:

I remember once, when I was but a little boy, someone gave me five cents. I never had so much money before. I felt rich. I thought, Why, these five cents will buy six sticks of candy! I raced into the house to ask my mother if I might not go to the store at once and buy that candy. My mother said, No, you may not go for it is Saturday evening and the sun will soon be setting. You must wait until Monday. I never felt so impatient about Sunday before. It came between me and the candy. Just then something seemed to say to me, Well, little boy, do you not think that you ought to give your five cents to the heathen? At that time I didn’t know who put that thought into my heart, but I had heard about a collection for missions announced to be taken on the morrow and I know now that God’s Spirit spoke to me then. He wanted to make me a missionary but I wasn’t willing. The heathen were far away. I didn’t know much about them and didn’t care. But I knew all about candy and it was only two miles away at the store. I was very fond of it and decided I must have it. But that didn’t end the struggle.

It was candy and the heathen and heathen and the candy contending for that five cents. Finally I went to bed, but couldn’t sleep. Usually as soon as my head touched the pillow I was off to sleep, but that night I couldn’t get to sleep because of the war going on between the heathen and candy, or between love and selfishness. At last the heathen got the better of it and I decided to go up to Sunday-school next day and put my five cents into the collection. I felt very happy then and in a moment was asleep. But when I awoke the sun had arisen and my selfishness had returned. I wanted the candy and the fight went on, but before Sunday-school time, love had gained a final victory and I went to Sunday-school and when the plate was passed around for the mission collection, I dropped my five cents in. And would you believe me, I felt more happy than if I had got a whole store full of candy! And so will any boy or girl who acts unselfishly for Jesus sake.

We are grateful to Dr. McNichol of the Toronto Bible College for the following sidelight on Jonathan Goforth at this period:

I remember the first time I saw Dr. Goforth. It was in the dining-room of old Knox College in the morning after my arrival in Toronto as a raw, green student. At breakfast I was seated close to the head of the table, where were grouped some of the graduates of the previous spring. Two of them were specially pointed out to me, — J. A. Macdonald, at the end of the table, and Jonathan Goforth next him at the corner.

I have never forgotten the sight of Mr. Goforth’s radiant and animated face as the talk went on, about the new mission which the Presbyterian Church was establishing in China that fall. That incident was the beginning of my own interest in foreign missions, and it has been continually fed since then by the radiant enthusiasm of his life.

We are also indebted to Miss. Mabeth Standen for the following letter. She was one of the most honoured and loved among the many Hidden Heroines of the China Inland Mission. It was my great privilege to have known Miss. Standen’s saintly parents who were among the early pioneers of Canada:

How well I remember the farewell meeting in our old church at Minesing just before Dr. and Mrs. Goforth left for China in 1888. I was much impressed by the large missionary map, the white spot indicating where the gospel was known, while the large remaining black surface spoke impressively of the millions who had never yet heard.

As Dr. Goforth closed his address he used an illustration that I never forgot. Referring to the miracle of the feeding of the five thousand, he pictured the disciples taking the bread and fish to the first few rows of the waiting and hungry multitude. Then he imagined these same disciples, instead of going on to the back rows, returning to those who had been already fed and offering them bread and fish until they turned away from it, while the back rows were still starving.

Said Dr. Goforth, What would Christ have thought of His disciples had they acted in this way, and what does He think of us today as we continue to spend most of our time and money in giving the Bread of Life to those who have heard so often while millions in China are still starving? God spoke to me that night about my responsibility regarding China and l promised Him then that if He opened my way, I would when old enough go to the back rows. Later on when other claims seemed insistent and one was tempted to care for the front rows only, the vision of China’s need as I had seen it that night always came before my eyes. I could not get away from it and finally said, Lord, here am I, send me — to the back rows.

In the spring of 1887, the Knox College students sent a deputation which included Jonathan Goforth, to plead their cause before the Synod of Hamilton and London, which was meeting that year in Chatham. On the Tuesday afternoon a member of the Synod suggested that a representative of the students be invited to address the meeting.

His fellow-students said to Jonathan, It’s up to you, Goforth; you do the preaching, we’ll do the praying. When he commenced his address that evening, Dr. —— who had been the chief opponent, was writing vigorously as though he were too busy to listen. But after several futile attempts to keep his mind on his writing he laid his pen down and from then on showed as keen interest in what was being said as the rest of the audience.

Dr. John Buchanan, of India, sends the following vivid and somewhat amusing, but characteristic, picture of Jonathan Goforth at this period:

Jonathan Goforth, though young, was even then, in 1887, a fearless prophet of Jehovah. I well remember when he and I were sent to Zion Church, Brantford. The Convenor for Home Missions, was pastor. Zion Church at that time gave almost exclusively to Home Missions. . . . At the very beginning of our service, Heber’s missionary hymn was announced and read in part, perhaps as a sort of concession to the visitors, —

From Greenland’s icy mountains,

From India’s coral strand. . .

Waft, waft ye winds His story,

And you ye waters roll,

Till like a sea of glory

It spreads from pole to pole.

but before the organ could sound, Jonathan Goforth, in his short homespun, much used brown coat, the sleeves wrinkled up till too short for his Elijah arms, was on his feet. In his left hand was the Church Blue Book, opened at the point where the Zion Church statistics were revealed; his prophetic eyes flashed; his right condemning forefinger pointed at the givings for foreign missions by Zion Church for the previous year.

No! he demanded, a congregation strong as Zion Church giving only seventy-eight cents per member a year for foreign missions, cannot sing such a hymn as that. We must sing a penitential Psalm — the 51st. The Psalm was sung with deep emotion. The stage was set!

But what was I, the first speaker to do? I began with fear and trembling on the great call that had come to us students. After speaking some time, I started on wasteful expenditures, when Goforth, always sure and never backward, from his seat behind the pulpit, pulled my (also short) coat tail. As I took no heed, again he pulled and whispered, Leave that to me, l am to speak on that. He was quite right! He had a lash prepared for those at ease in Zion.

Like his Master, Goforth had a great compassion for the needy and helpless and a two-edged flashing sword for the self-satisfied Christian Pharisee. It was probably this searching penetrating method of preaching to bodies of even Christian workers that caused opposition to his being sent, as was urged years later, on a Mission tour in India as he had in China.

Thus all opposition melted away before the enthusiasm of these missionary-minded students. The missionary vision captured the Presbyterian Church of Canada as it never had before. Churches, which formerly had barely given a thought to the foreign field, made themselves responsible for the support of missionaries. At the General Assembly in June of 1887, Jonathan Goforth and Dr. J. Fraser Smith of Queens were appointed to China. In the following October, Goforth was ordained, and on the twenty-fifth of the same month, was married to Florence Rosalind Bell-Smith in Knox Church, Toronto, the beloved pastor, Rev. H. M. Parsons, D.D., conducting the ceremony.

After Goforth’s ordination, the Foreign Mission Board planned for him to go through the churches, giving his addresses on foreign missions until Dr. Smith was through his course, that the two might go together for the finding and founding of the new mission in China. But early in January of 1888, reports of great famine raging in China decided the Board to hasten Goforth’s departure so that he might carry with him considerable funds which had been raised for famine relief and might even engage in famine relief himself.

Of that wonderful farewell meeting, words fail one to describe. On January 19, 1888, the old, historic Knox Church was filled to capacity. The gallery was crowded with students from Knox and other Colleges. Among those on the platform were the Hon. W. H. Howland, then Mayor of Toronto, one of the most honoured and loved Christian workers Toronto has ever known, Principal Caven and Professor McLaren of Knox, Rev. Dr. H. M. Parsons, and Goforth’s closest friend, Rev. William Patterson.

One story was told at that farewell meeting which made a deep impression on all present and touched a note which sounded through the Goforth’s whole after career! The story was of a young couple, when bidding farewell to their home country church as they were about to leave for an African field, known as The White Man’s Grave. The husband said, My wife and I have a strange dread in going. We feel much as if we were going down into a pit. We are willing to take the risk and go if you, our home circle, will promise to hold the ropes. One and all promised.

Less than two years passed when the wife and the little one God had given them, succumbed to the dreaded fever. Soon the husband realized his days too were numbered. Not waiting to send word home of his corning, he started back at once and arrived at the hour of the Wednesday prayer-meeting. He slipped in unnoticed, taking a back seat. At the close of the meeting he went forward. An awe came over the people, for death was written on his face. He said:

I am your missionary. My wife and child are buried in Africa and I have come home to die. This evening I listened anxiously, as you prayed, for some mention of your missionary to see if you were keeping your promise, but in vain! You prayed for everything connected with yourselves and your home church, but you forgot your missionary. I see now why I am a failure as a missionary. It is because you have failed to hold the ropes!

Each speaker at that meeting seemed eager to have a share in sending the Goforth’s off with joyful enthusiasm. At the close of the two-hour meeting practically all pressed forward in line to shake hands with Mr. and Mrs. Goforth — for days their right hands pained with the grips given them! Their train was to leave at midnight from the Old Market station half a mile distant. Soon after eleven o’clock, hundreds started for the station, among them, Principal Caven with his professors and students.

Toronto probably never witnessed such a scene as followed. The station platform became literally packed. Then hymn after hymn was sung. As the time drew near to start, Dr. Caven, standing under a light in the midst of the crowd, bared his head and led in prayer. A few moments later, as the train began to move, a great volume of voices joined in singing Onward Christian Soldiers — hands were stretched out for a last clasp, — then darkness. Jonathan Goforth’s new life had begun, and, incidentally, his training of Rosalind!

Chapter V

For Christ and China

I gave up all for Christ, and what have I found? I have found everything in Christ! JOHN CALVIN

AS THE last glimpse of the waving friends vanished, Goforth turned to his wife and bowing his head prayed that they might live worthy of such confidence. Of the first journey to the coast but little need be said. The remembrance of their reception at Winnipeg and the warmth and courtesy shown them by Principal King, of Manitoba College, with whom they stayed, remained with them through the years. In her diary of January 25, 1888, Mrs. Goforth writes:

Mrs. McLeod and a number of others met the train at Portage la Prairie. Each one was loaded down with all sorts of good things. There was a goose, a chicken, a roast of beef, pickles, preserves, apples, honey, etc., etc.

Jan. 29th: Delayed so much by snow drifts and washouts, we are now thankful for the good things brought to us at Portage la Prairie. Though at the time the amount seemed burdensome, we have needed it all, sharing with others who like ourselves are travelling tourist. On Sunday, J. had two meetings on the train, both well attended.

On reaching Vancouver, they found the city, which but a short time before had been swept by a devastating fire, little more than a heap of charred ruins. No time was lost in seeking out their boat, the S.S. Partha. To their unsophisticated eyes, the vessel seemed quite splendid, and it was with the utmost joy and hopefulness they began settling in their cabin.

The following is taken from a letter written by Goforth dated Vancouver, February 4, 1888:

Just a few words before our pilot leaves us. . . We went on deck at 7 o’clock this morning and watched the ship loosed from her moorings. We had not the slightest wish to stay though strong emotion filled us at thought of leaving native land, — more properly, those of you our friends who made Canada a dear spot to us. I never saw Mrs. Goforth more happy than now as we turn out into the ocean towards our future home. Let us leave no stone unturned in the effort to move God’s people to spread the message to every creature. I know that many eyes are fixed on this movement. It rests with us either to inspire or discourage the host of God forming our church. We have the aid of many prayers. The means sufficient shall certainly not be wanting. Let us win ten thousand Chinese souls. It will please him, our Lord. (How fully was this fulfilled in the years to come!)

The first rather jolting surprise came when it was learned Mrs. Goforth was the only woman passenger! Then, just after they had passed through the straits and were facing out to sea, a strange hubbub was heard outside their cabin. It was found to be caused by several of the boatmen half hauling and half carrying the captain, a large man, down to a lower cabin, dead drunk!

The remembrance of the fourteen days that followed ever remained to Mrs. Goforth, at least — a terrible nightmare! They tried to comfort themselves by the thought that they were only going through what all ocean travelers have to put up with, but the truth finally came out.— They discovered that for twenty-five years the Partha had plied the Atlantic, but under another name. As the years passed, the vessel acquired such a notorious reputation for its rolling, pitching, and heaving that none would take passage on her. So the officers had the boat repainted, renamed the Partha and put on the Pacific run.