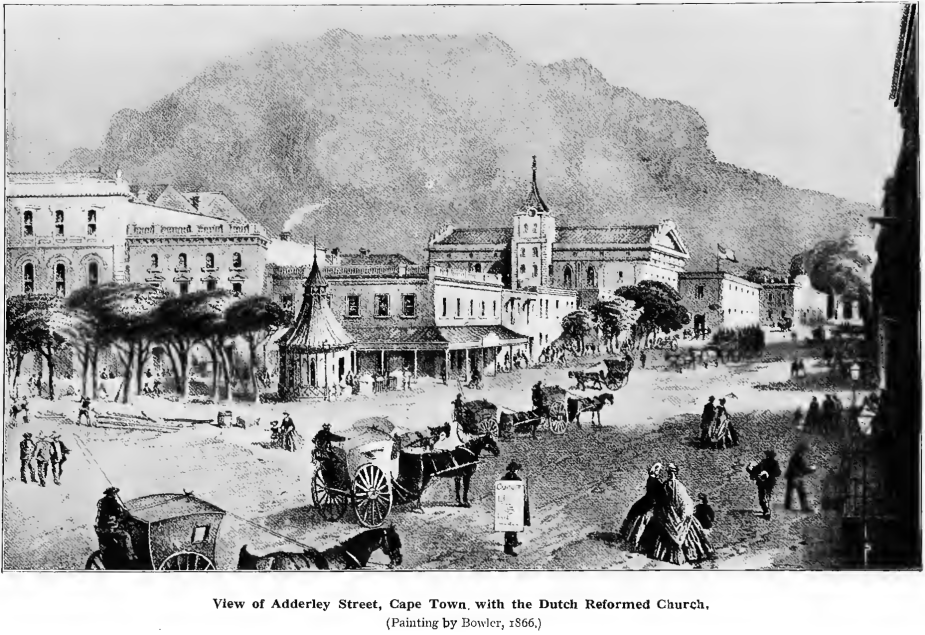

Physical configuration of South Africa—First colonization by the Dutch—Gradual increase of population and extension eastwards— Surrender of the Colony to the English—Substitution of English for Dutch as official language—Position of the Dutch Reformed Church—The three factors in the situation—The two white races of South Africa—Andrew Murray’s relation to both—Historical events during Andrew Murray’s lifetime—His sympathy with his people—General condition of South Africa in the middle of the nineteenth century.

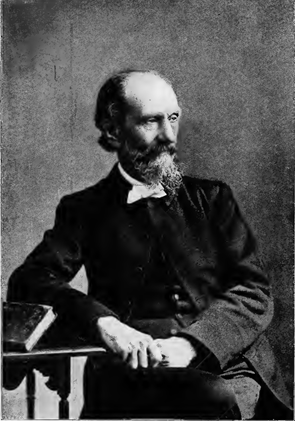

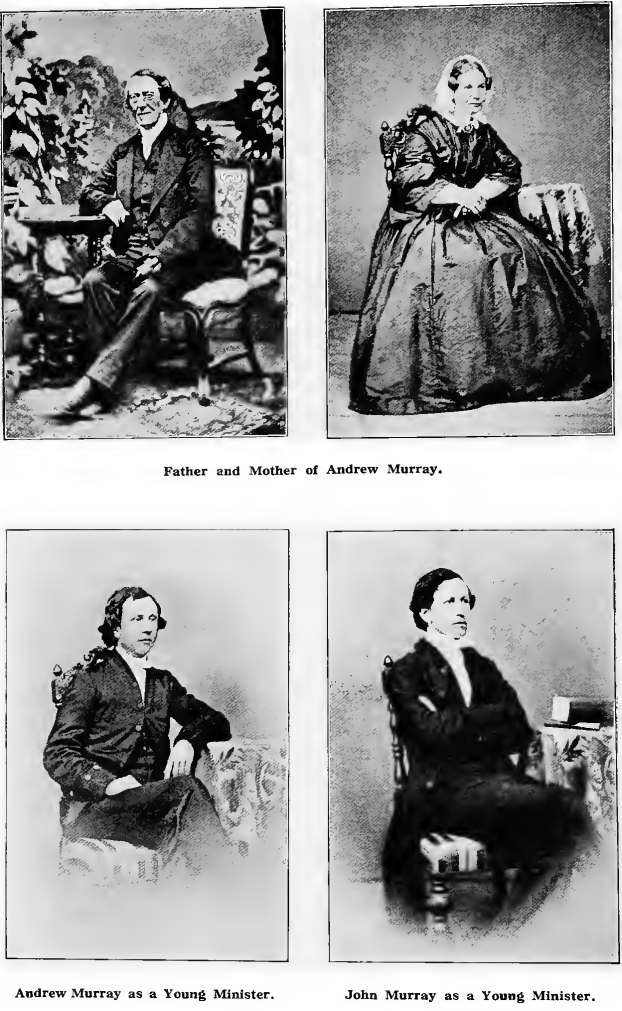

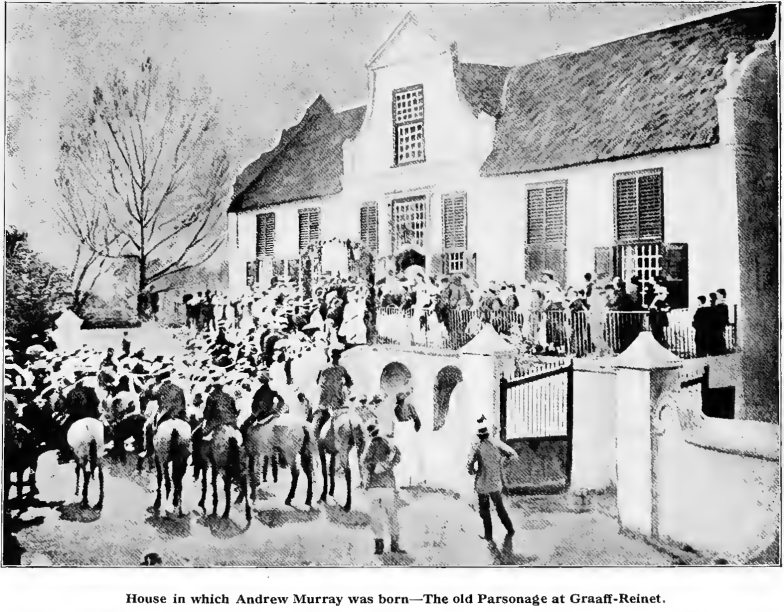

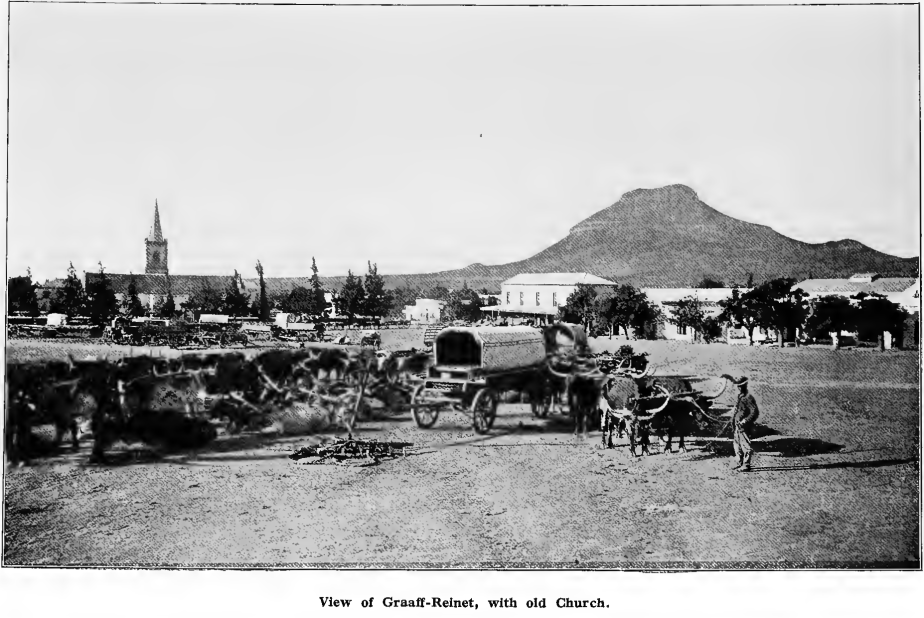

Paternal ancestry—Andrew Murray of Clatt—John Murray of Aberdeen—Family connexions in Scotland and Canada—Andrew Murray, the father—Letter of Dr. George Thom on ministers for South Africa—Appointment of Andrew Murray Sr.—His diary of the voyage to South Africa—Departure—Fellow-travellers—On the rocks at the Cape Verde Islands—Prolonged voyage—Arrival in Table Bay—Andrew Murray Sr. appointed minister of Graafi-Reinet—Description of the place—The parsonage—Andrew Murray’s marriage to Maria Susanna Stegmann—His attachment to the land and people of his adoption—His pastoral activity—Vis its of missionaries—Home life—The father's deep spirituality—The founding of new congregations—Reminiscences of the mother— Journeys to Cape Town—Birth of Andrew—His character as a child.

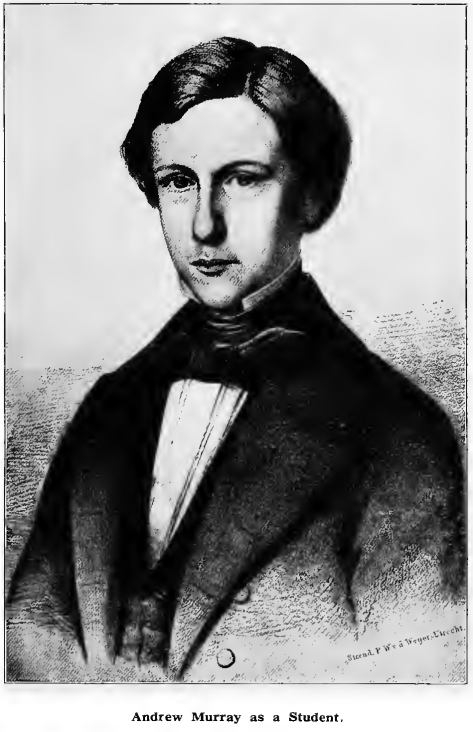

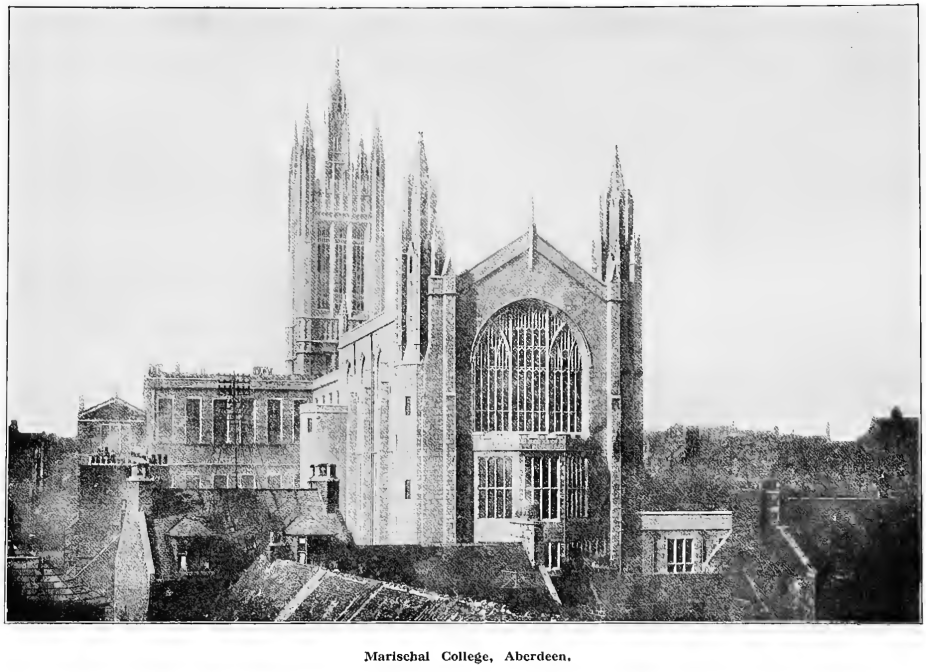

Backward state of education at the Cape in the thirties—The Bible and School Commission—Departure of John and Andrew Murray for Scotland—The old Grammar School of Aberdeen—Letters of Andrew Murray Sr. to his sons—William C. Bums and the Scottish revivals—Bums’ preaching and its results—His labours at Aberdeen—Impression made upon Andrew Murray—Letter of Bums to John Murray—Events leading up to the Disruption of the Church of Scotland—Andrew Murray Sr. to his sons—Andrew Murray to his parents and sister—His decision to become a minister—His graduation at Marischal College—Andrew Murray Sr. to his sous on life in Holland.

Departure of John and Andrew Murray for Holland—Description of first meeting between them and N. H. de Graaf—Religious condition of Holland—The RSveil—Sechor Dabar—Eltheto—Comparison with the Methodists—The theological professors—Influence of C. W. Opzoomer—Andrew Murray’s conversion—Letter to his parents—Friends in Holland—Letter suggesting further study in Germany—John Murray on conditions in Holland—Arrival of Neethling, Hofmeyr and Faure from South Africa—Ordination of John and Andrew Murray at The Hague—Farewell meeting with the members of Seckor Dabar—Benefits of the sojourn in Holland —Arrival in Cape Town—Letter to his parents—Reunion with the family circle—Appointment to Bloemfontein.

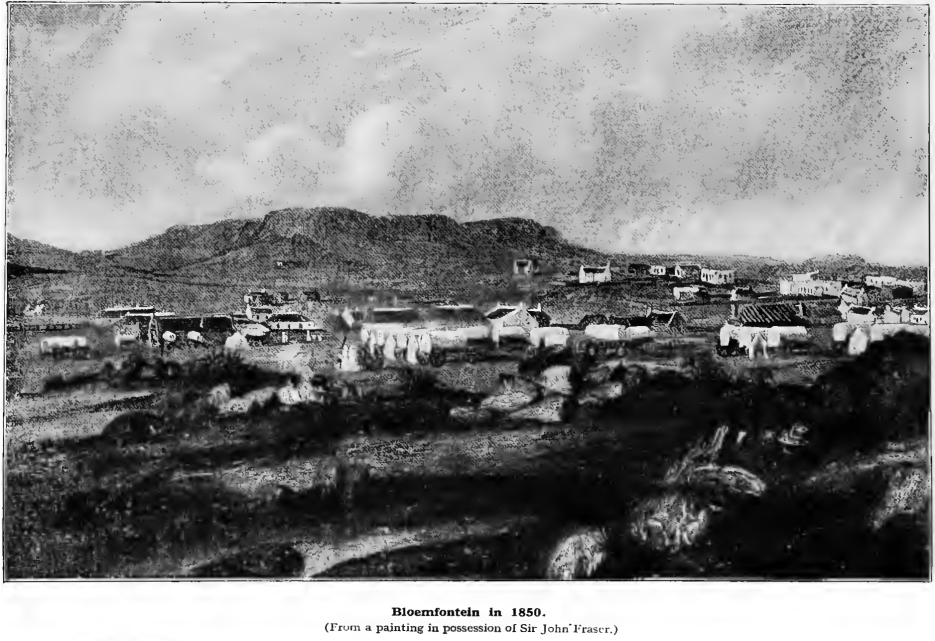

The Dutch Reformed Church in South Africa—Its dependence upon Holland—The Church Order of 1803—The Church’s Magna Charta—Dearth of ministers—The Great Trek—Fortunes of the emigrants—Proclamation of the Orange River Sovereignty—Battle of Boomplaats—Andrew Murray’s settlement in the charge of Bloemfontein—Visit to Mekuatling mission station—Induction of John Murray at Burgersdorp—Circumstances and nature of the work at Bloemfontein—Description of Bloemfontein in 1849— Unsatisfactory relations of farmers and natives—Andrew Murray’s labours and travels—First meeting of Legislative Council— Unrest on the frontier—Communion services—Foundation-stone of Riet River church laid—Murray’s extensive parish.

Importance of Murray’s first pastoral tour among the Transvaal emigrants—Visit to Mooi River—The “ Jerusalem Pilgrims ”— The Magaliesberg—A letter of invitation from Commandant Potgieter—Meeting with Andries Pretorius—Serious indisposition —Journey to Ohrigstad—Return to the Magaliesberg—Sitting of the Volksraad—Large attendances at services—Praying for the authorities—Return journey to Bloemfontein—Death of Deacon Coetzer—Continued unrest on the Basuto border—Arrival of teachers from Holland—Correspondence—Visitors—Narrow escape at Kaffir River—Visit to Graafl-Reinet and return—Preparations for a second journey to the Transvaal—Departure— Arrival at Mooi River—Visit to Suikerbosch Rand and Lydenburg —Great fatigue—Visit to the Warm Bath—Reach the Magaliesberg —Continued fatigue—Zwarte Ruggens—Morikwa—Andrew Murray put on trial—Schoonspruit—Arrival of Rev. D. van Velden, and induction at Winburg—Andrew Murray called to the Transvaal— The call declined.

Third visit to the Transvaal—Native unrest—Disastrous battle at Viervoet—Andries Pretorius invited to restore order—Andrew Murray on the situation—His visit to Pretorius—Commissioners Hogge and Owen—The Sand River Convention—Fourth Transvaal visit—Neethling’s description of a service—Method of travel —Respect paid to the ministers—The Zoutpansberg emigrants—Services there—Commandant Hendrik Potgieter—Manifold labours—Visit to a farmer under sentence of death—Arrival in the Transvaal of Rev. D. van der HofE—His doings—His letter to Andrew Murray —Secession of Transvaal congregations from the Cape Church— Missive addressed to Rev. van Velden—His letter of rebuke and warning—Reasons for the Secession—Later history of the Transvaal congregations.

The Synod of 1852—Events in the Sovereignty—Battle of Berea— Decision of the British Government to abandon the Sovereignty— Meeting of people’s delegates at Bloemfontein—Account of J. M. Orpen—Resolutions passed—Dr. Frazer and Andrew Murray delegated to England—Further events in the Sovereignty—Convention of Bloemfontein signed and Orange Free State established— Proceedings of Messrs. Frazer and Murray in England—Preaching engagements of Andrew Murray—His visit to Holland—Meeting of the Ernst-en- Vrede party at Amsterdam—Visit to Scotland—Feeble health—Visits to water-cure establishments—Second visit to Holland. and visit to the Rhineland—Return to South Africa.

Calls to Colesberg and Ladysmith—Regarding books and congregational questions—Founding of the Grey College—Marriage The Rutherfoord family—Quiet work at Bloemfontein—War between the Free State and the Basutos—Letter to H. E. Rutherfoord— Birth of a daughter—The Synod of 1857—The question of a theological seminary—Missionary expansion—Arrival in South Africa and doings of Rev. D. Postma—Murray’s first published book— Grey College questions—The Separatist movement in the Transvaal and at Bloemfontein—Murray’s attitude—Disapproval of the Presbytery—Calls to various congregations declined—Call from the congregation of Worcester accepted—Preparations for departure—Farewell to Bloemfontein.

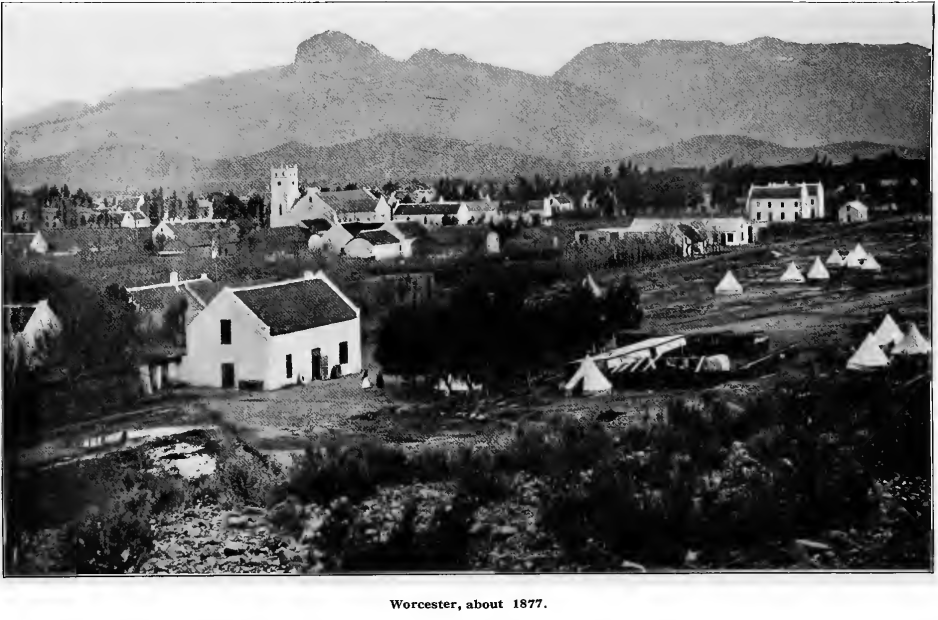

Situation of Worcester—Its spiritual condition—The Worcester Conference—Andrew Murray on the proposed Conference—Dangers of the Church—Proceedings of the Conference—Resolutions passed —Murray’s speech in moving resolutions—The need of ministers and teachers—Dr. Robertson deputed to Europe—His letter from Holland—Success of his mission—Induction of Murray at Worcester—Commencement of a revival—Character of the movement— Description by Rev. J. C. de Vries—Extraordinary scenes—Professor Hofmeyr on the results of the revival—Emotional element— Moral changes effected—Extent of the movement—New zeal engendered—Testimony of Rev. C. Rabie—Spread of the revival— Home life at Worcester—Missionary journey to the Transvaal— Letters to wife and children—Stay at Paul Kruger’s—Spiritual experiences there—Commencement of Zoutpansberg and Rusten-burg missions—Literary labours.

The "Liberal” movement in Holland and at the Cape The “Church Order” and the “Ordinance”—Synod of 1862 Wreck of the Waldensian—Description of the Synod by Rev. F. L. Cachet —Andrew Murray, moderator—Other leading members Elder Loedolff's objection—Orthodox and Liberal parties—Supreme Court judgment—Disruption of D. R. Church—Withdrawal of members affected by judgment—Rev. J. J. Kotz6 of Darling on the Catechism—A second Supreme Court case—Favourable judgment—Resolution to suspend Kotz6—Events in the Darling congregation—Meeting of Synodical Committee—Kotzb versus Murray_ Speech of the defendant—Murray complimented by Justice Bell— Adverse judgment—Principles on which it was based—Apparent victory of Liberalism—Case of Rev. T. F. Burgers—Burgers suspended—Burgers versus Murray—Judgment—Proceedings in the presbyteries—Continued litigation—Appeal to Privy Council— Murray deputed to England—Appeal fails—The Synod of 1867 and its immediate adjournment—Reasons for decline of Liberalism— Establishment by Rev. D. P. Faure of the " Free Protestant Church ”—His sermon in the Cape Town church—Gatherings in the Mutual Hall—Synod of 1870—Resolution adopted by the moderate party—Protest of the minority—Suppression of Liberalism in the D. R. Church.

Visit of Dr. Duff to South Africa—Andrew Murray to his father —Call and removal to Cape Town—Andrew Murray Sr. refused leave to preach by the consistory of Hanover—Murray's colleagues at Cape Town—Death of Andrew Murray, the father—Letter of Andrew Murray to his mother—Stay in Europe—Birth of a son—

Call to Marylebone Presbyterian Church—British sympathizers with the Liberal movement—D. P. Faure’s lectures—Murray’s discourses on “ Modern Unbelief ”—His lecture in the Commercial Exchange—Rev. G. W. Stegmann Jr. elected as Murray’s colleague —Secessions from the D. R. Church—Murray’s sermon—Strictures by D. P. Faure—Murray’s controversy with Kotz6 on the Canons of Dort—Home life in Cape Town—Children of the family—Sojourners under the Murrays' roof—Extent and need of the Cape Town congregation—Murray’s interest in young men—Y.M.C.A. founded—Proposals for union between the Anglican and D. R. Churches—-Bishop Gray’s views—Remarks thereon by Messrs. Murray, Faure and Robertson—Gray’s reply in Union of Churches —Failure of negotiations—Zahspiegeltjes—Literary work—The call to the pastorate of Wellington.

The Wagonmaker’s Valley—-Situation of Wellington—Problems of the new sphere of work—The Voluntary Question—Mission work— Departure of the two eldest daughters for Holland—Letters to the daughters at Zeist—Journey to Swellendam—On the study of Dutch—On Home Mission work—Death of two younger children—Birth of a son—Arrival of lady teachers from America—-Articles on Our Children—Appeal for girls to be trained as teachers—Study of Mary Lyon’s life—Papers on the subject—Huguenot Seminary founded—Circular on the school—Generosity of the Wellington congregation—Purchase of a site—Opening ceremony, 25 October, 1873—Formal commencement of classes, January, 1874—Mr. Murray’s tour of collection—His welcome home—Building extensions—Report on progress made—R. M. Ballantyne on the Huguenot Seminary.

Popular education at the Cape—The task of the Dutch Reformed Church—Mr. Murray’s influence—A second collecting tour—Urgent letter on the need of more workers, as ministers, catechists and teachers—Moderator for the second time—Opening of the Mission Training Institute, October, 1877—Its objects described—Delegate to the first Pan-Presbyterian Council in Edinburgh—Aims of journey outlined—Visit to America—Lady teachers secured—Rev. George Ferguson and Mr. J. R. Whitton—Impressions of the Pan-Presbyterian Council—Professor Flint’s sermon—Public reception —Dr. Schafi on the Confessions—Professors Godet and Krafit—Drs. Cairns and Hodge—Paper by Dr. Duff on Missions—Conference on life and work—Sunday services—Drs. Patton and McCosh on Unbelief—The Spiritual Life—Closing meetings—Value of the Council—Conference at Inverness—Letter to his wife—Brief trip to Holland and Germany—Return to South Africa—Letter of a lady teacher on Mr. Murray’s tour—His welcome back to Wellington —Commencement of classes at the Training Institute—Paper on aims and needs of the institution—Training Institute versus Normal College—Growth of the Institute.

Intellectual dependence of South Africa upon Europe—Its religious dependence—Andrew Murray’s position and influence—Influence of the Holiness Movement—Mr. Murray on spiritual intercourse —The Colesberg Conference of 1879—-Criticism evoked—Reply of Mr. Murray—Strictures on his teaching in letter by “V.D.M.”—Mr. Murray’s defence—Influence on South Africa of the work of Moody and Sankey—Committee for special Gospel-preaching—Mr. Murray’s observations on the religious needs of the rural population —His paper on Special Services—Two months’ tour through the Midland districts—Glen Lynden and Adelaide—Spiritual results.

Mr. Murray suffers from a relaxed throat—Rest in the Karroo— Sojourn at Murraysburg—The Transvaal War of Independence—The feeling of nationality—Movements of his daughter Emmie Return to Wellington—Literary projects—Abide in Christ—Prof. John Murray in Europe, and his return to South Africa—Set-back in the condition of Mr. Murray's throat—Departure for England— Wm. Hazenberg on Faith Healing—Pastor Stockmaier on the same subject—At Bethshan Institute of Healing—Instruction by Stockmaier—Discussion with Boardman—And with Stockmaier— Cures effected by faith—Jezus de Geneesheer der Kranken— The principles of Faith Healing expounded—Later attitude of Mr. Murray—The case of Rev. P. F. Hugo—And of Rev. P. Stofberg— Cure of Miss McGill—Final remarks.

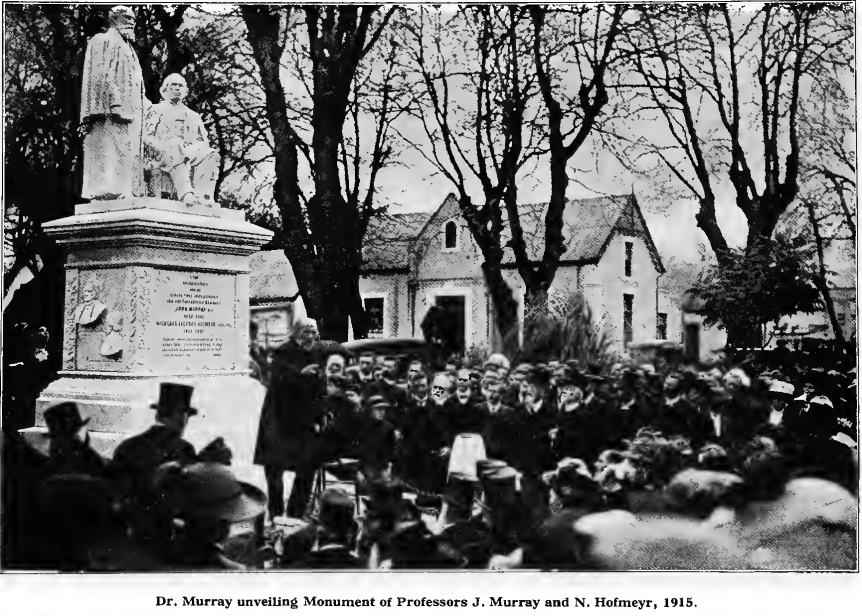

Mr. Murray six times Moderator of Synod—His view of his task— His special qualifications—Powers of work—Ability and tact as chairman—Gifts of leadership—Interest in Sunday-school work— The aims of the Sunday-school defined—Establishment of the Bible and Prayer Union—The subject of prayer—The Andrew Murray Prayer Union—Controversy on the total abstinence question— Professor Hofmeyr’s attitude—Antagonism of the wine-farmers— The question in the Synod—Review of Rev. S. J. du Toit’s book, De Vrucht des Wijnstoks—End of the controversy—The union of the Dutch Reformed Churches—Mr. Murray’s share in the movement towards union—The Council of the Churches—Proposals for union—Parliamentary legislation—Rejection of the union proposals—Ministerial jubilee, 1898—Address presented—Mr. Murray’s reply.

Mr. Murray’s early interest in missions—His influence as missionary leader—Establishment of the Ministers’ Mission Union—Question of a new field of work—Letter of the executive—Commencement of work in Nyasaland by A. C. Murray and T. C. B. Vlok—The crisis of 1899 and call to prayer—The Anglo-Boer war and its influence —Transference of the Nyasa field to the Synod—The deficit of 1908, and the mission congresses—Mr. Murray on deputation work—Mr. Murray’s connexion with the Cape General Mission—Spencer Walton’s first visit to South Africa—Services in the Exhibition Building —Appreciation of Walton's work—Cape General Mission founded— Its objects—Holiness conventions—Inauguration of the South African Keswick—The new departure in Swaziland—Enlargement of the C.G.M. to the South Africa General Mission—New fields— Estimate of Mr. Murray’s influence hy A. A. Head—Mr. Murray’s writings on missionary subjects—The Key to the Missionary Problem —The four principles enunciated—Impression produced by the book—Results of the week of prayer for missions in South Africa— The Kingdom of God in South Africa—Prayer in missions.

Early Interest in education—Baptismal Sunday—Founding of Grey College—Dr. Brill’s appreciation—Educational undertakings in the Western Province—Mary Lyon’s influence—The Huguenot Seminary and other girls’ schools—Teachers’ conference at Worcester—Institutions affiliated to the Huguenot Seminary—Good-now Hall—Address of Mr. Murray on education—Training Institute —Popular education for the rural districts—Circuit schools—Poor whites—Address at Fraternal Conference—Present position of "poor whites” question—The teaching of Dutch—Report of Committee on the question—The “ Taal Bond ”—Influence on Mr. Murray’s educational views of Thring’s Life—And of Spencer’s Sociology—Letter to his daughter—Degree of D.D. from Aberdeen University—And of Litt.D. from the University of the Cape of Good Hope—Dr. Walker on the graduation ceremony.

Andrew Murray’s love for his native land—His devotion to his'flock in the Free State and the Transvaal—Paper in the Catholic Presbyterian on The Church of the Transvaal—Chari Cilliers—Religious attitude of the Transvaal Boers—Their attitude towards the natives—Their spiritual life—History of the Transvaal—The Annexation of 1877—The Boers appeal to arms—Independence secured—Growth of the feeling of nationality in South Africa— Dangers of the situation—Kruger and Rhodes—The Jameson Raid —Embittered feelings—Jan Hendrik Hofmeyr—Commencement of hostilities—Mr. Murray’s papers in the South African News— His Appeal to the British People—His support of the Boer cause— Intercourse with Christian brethren uninterrupted—Views on the feeling of nationality—The Women’s Monument at Bloemfontein —Description of the ceremony of unveiling—Mr. Murray’s address on the occasion—Letter to Dr. D. F. Malan—Mr. Murray’s endeavours to heal ecclesiastical dissensions—Letter on the "national sentiment.”

Impossibility of measuring Mr. Murray’s influence—His evangelistic labours—Preparation for meetings—Letters written on his tours —Conference at Somerset East—Visits to Dordrecht, Barkly East Lady Grey and Maraisburg—Overseas evangelists in South Africa' —Dr F. B Meyer’s appreciation—The Ten Days of Prayer observed by the D.R. Church—Andrew Murray’s influence as a writer —Visit to Europe and America in 1895—Appreciation by Rev. H. V. Taylor—Welcome at Exeter Hall—Addresses at Keswick—Rev. Evan H. Hopkins on bis message—[Visit to America—North- -field—Chicago—^Evangelistic services in Holland—Closing meetings in London—Description in The British Weekly—Mr. Murray’s account of bis spiritual growth—The influence of William Law—Law’s career and published works—Mysticism—Bernard of Clair-vaux—Meister Eckhart—The " Friends of God ”—Jacob Bohme— fObj ections to mysticism—Andrew Murray’s avoidance of the errors of mysticism—His estimate of Law’s weakness and strength— Wesley’s dispute with Law—Andrew Murray the reconciler of the views of both—Dr. Whyte on Andrew Murray's spiritual autobiography.

Early literary efforts, how occasioned—Books written at Worcester —Blijf in Jezus—Abide in Christ—The School of Prayer—Professor James Denney on The Holiest of All—How the books were written—The books of later years dictated—How the “ Pocket Companion ” series originated—Andrew Murray’s style—The eloquence of intense earnestness—Illustration from The Holiest of All— Methods of work—Periods of literary production—Messages delivered at critical junctures—The State of the Church and its influence—Translations into other tongues—Influence of bis books in China—The publisher of the German editions—Letters of correspondents on blessing received—Extracts from the letters—In Time of Trouble, say—Letter from Dr. Alexander Whyte—Mr. Murray’s reading—Influence of William Law—Mr. Murray’s interest in mysticism—Books on prayer—Projected writings—Quotations from books—Remarks on books read.

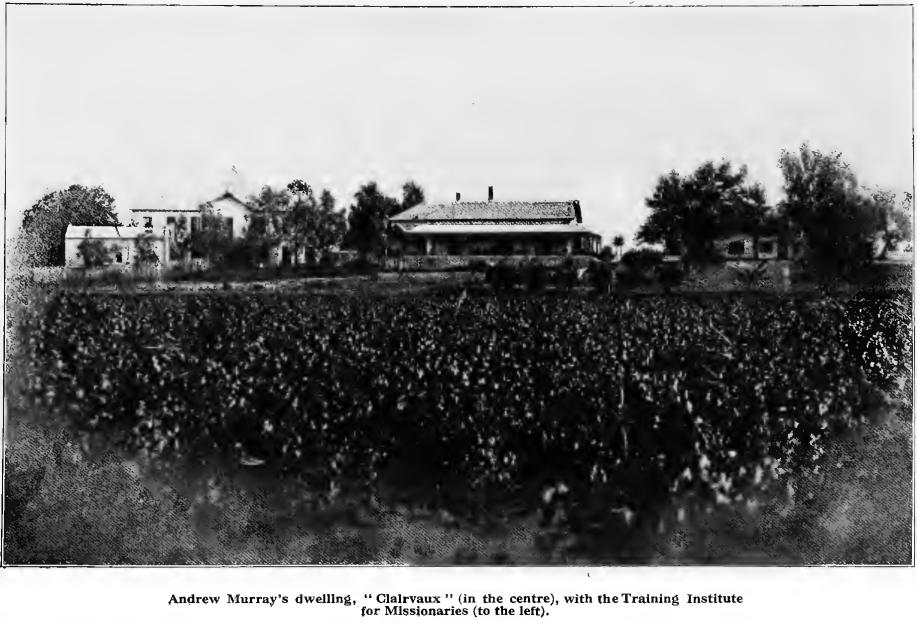

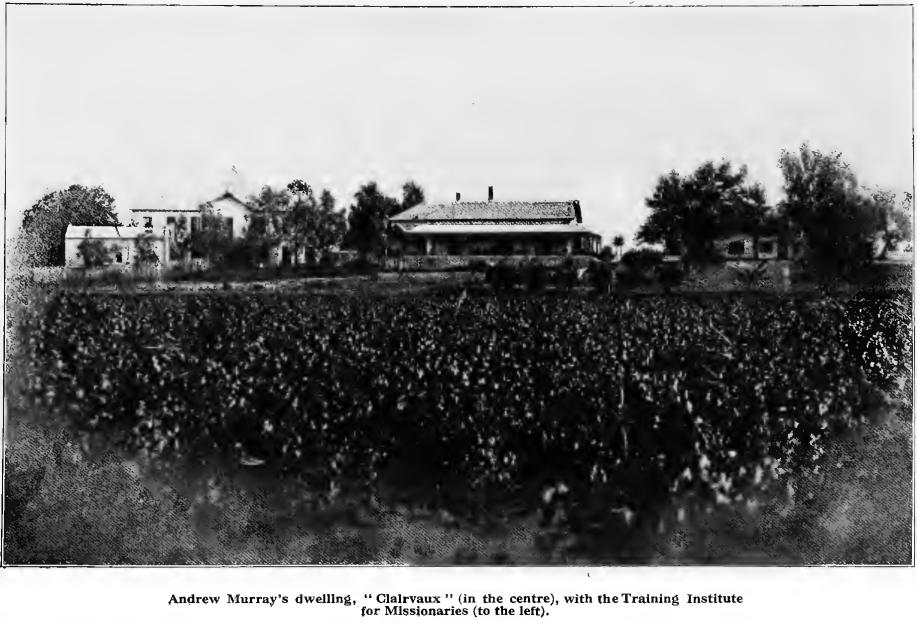

Life at Wellington—The Parsonage—Clairvaux—Mrs. Murray—Her activities and influence—The children—Death of Haldane Murray—The family hymn—Circular letter—A family re-union at Kalk Bay—Addresses on the beach and in the church—One-day conferences—Mr. Murray in the pulpit—A typical day described—A journey in his old age—Reminiscences at Graaff-Reinet, Bur-gersdorp and Bloemfontein—Cart journey to Rhodes—Goings and doings a year before the end—Details of Mr. Murray’s personal life —His sense of smell and colour—His love for children—Praying in his sleep—Outlined reply to Berlin professors—Sense of humour —Gift of illustration—"Sweet reasonableness”—Advice in difliculties—Pertinent sayings—Ability to speak the fitting word— Services in connexion with the death of Rev. William Murray.

Chronological Outline of the Life of Andrew Murray. 519

- Bibliography of Andrew Murray’s published works chronologically arranged by D. S. B. Joubet.

I often know not what to think of the leadings of Providence, in how far it may have been in tender mercy to my own soul that I was prevented from going thither [as minister to the Transvaal] ; although the letters I sometimes receive make a very strange impression upon me. All the people, otherwise so divided, are united in fixing their choice upon me.—Andrew Murray.

THE visit which Murray paid to the emigrants across the Vaal River was brief in its duration, but momentous in its consequences. The whole tour lasted but little more than six weeks. He crossed the Vaal on the 7th December, 1849, and re-crossed it on his homeward journey on the 22nd January, 1850. During this period he must have covered, north of the Vaal River, a distance of some 800 miles, and that chiefly by ox-waggon. He preached at six different centres, conducting in all thirty-seven services ; he baptized 567 children ; and he admitted to membership 167 young people, being less than half the number of candidates that presented themselves.

The far-reaching results that flowed from this visit were of an importance out of all proportion to its length. There existed on the part of the emigrants across the Vaal a not unintelligible suspicion towards ministers of the D. R. Church of the Cape Colony, which was at that time strongly tinged with Erastianism. Its clergymen were appointed by the Governor ; their salaries were paid out of the public treasury ; and though a certain latitude was permitted them in the acceptance or refusal of calls to particular congregations, the formal approbation of the Governor was requisite if the call was to be sustained. These regulations obtained in the case of Andrew Murray, who had received his appointment as minister of Bloemfontein from Sir Harry Smith, and drew his stipend from the Colonial Treasurer. It was natural for the emigrant farmers, who had trekked to the far north in order to escape from British influence, to look askance at a young minister who held his sacred office through the grace of a British Colonial Governor. The importance of Murray’s first visit lay in the fact that it allayed the suspicions of the Boers, knit their hearts to the ardent young pastor who brought them the ministrations of grace, and evoked expressions of confidence1 in the Cape D. R. Church, and of a desire to remain in corporate ecclesiastical communion with that body.

Of the details of this tour of visitation we have happily full accounts, both in the Kerkbode, and in letters addressed by Murray to his father. We shall therefore let him tell the story in his own words, with but an occasional elucidatory comment.

To his Father.

Magaliesberg, 22nd December, 1849.

I should certainly ere this have begun to write some account of my journey, but have hitherto been prevented, I may say, by a press of business ; for the little spare time I have had has generally been on the road, when I could not conveniently sit down and write. I trust you received the hurried lines I sent you from Mooi River [now Potchef-stroom] in which I told you of my arrival there. I was received with the greatest friendliness and apparent confidence, though I believe there had been some doubts on the part of the Landdrost as to whether he would allow me to come, for fear of British influence. The congregation was large, but I found it very difficult to fix their attention, evidently from their long separation from the means of grace. I trust that some impression was produced, if I may judge from their talking about the sermons. On Monday I had sixty-five candidates for membership, of whom thirty-two were received; and I was really astonished at the way in which many could read. On Monday evening I held my last service, at which they were voorgesteld (presented).

On Tuesday morning we left for the Zwarte Ruggens, to the northwest of Mooi River. The Landdrost Lombaard took me out on horseback, and with him I had a good deal of conversation about the state of the country, especially of the Morikwa, whence he had just returned.

The second church-place ought to have been there, but for want of time it had been appointed on the borders of that district. It was expected that we should there have the largest congregation, but on our arrival (after three days' travelling in an ox-waggon) we found that the congregation was smaller than at Mooi River. The people in the Morikwa are most unsettled, and a few ringleaders lead them astray, especially in religious matters. The most of those who are waiting for the trek to Jerusalem are in that neighbourhood, and I was very sorry that my further arrangements prevented my going among them, though this perhaps was also the Lord’s doing, as they might possibly have turned me back.

On Friday I spoke the whole day to the parents of the children brought for baptism, and held a service in the evening. On Saturday morning and evening there was preparation, and between the services I spoke to the most of those who wished to partake of the Lord’s Supper, which was dispensed on the Sabbath, and of which some sixty partook. Many of these appeared to feel the solemnity of the occasion, while others, although I had tried to speak as plainly and faithfully as I could, gave too plain proofs that they came without the proper preparation. I trust, however, that the Lord was with some of us. I was very much pleased with Caspar Kruger, the deacon, from whose place I am writing, as the church is to be held here to-morrow. He says that he there first was enabled to rejoice in Christ, though long seeking after Him. It is the first time that he has partaken of the Sacrament. He acknowledges that he has long, through the obstinacy of his heart, rejected Christ.

On Wednesday we left for Gert Kruger’s, your friend. On the way we called on one of those who refuse to come to church. After a couple of hours’ conversation I left him, deeply grieved at the ignorance of these poor people [i.e. the “ Jerusalem pilgrims ”]. England is one of the horns of the beast, and of course those who receive her pay are made partakers of her sins. I hardly knew whether to weep or smile at some of his explanations of the prophecies and of Revelation, all tending to confirm their hope of being soon called to trek to Jerusalem. By the way, he for the moment quite puzzled me by showing me the kantteekening [marginal note of the Dutch version of the Bible] on Revelations xvii. 12, where all the countries of Europe are mentioned as being typified by the horns of the beast, except Holland,—and under it he included, of course, the true Africaners.2

In the afternoon I rode to Gert Kruger’s, where I was most warmly received. With him I had a great deal of conversation on the state of the country, from which, as well as from my own observation, I really think that the people are getting settled (though there are a few malcontent spirits here and there), and many are beginning to do very well indeed. Gert Kruger says he considers either John or myself their rightful possession from the promise you made at Mooi River. I really know not sometimes what to answer the people—they do so press me to come here. I must acknowledge that, were I not bound to Bloemfontein, which I have not the least desire to leave, I could not refuse their request. You may perhaps think that I have not sufficiently weighed the difficulties which present themselves here, but I think I feel them. The field is really ripe for the harvest, and many, many are longing for the preaching of the Word, though with others it is nothing but a desire for the sacraments.

Yesterday morning I arrived here at Caspar Kruger’s, after having crossed the Magaliesberg. The country along both sides of the mountain is really beautiful and very fertile. It is not so flat as about Mooi River and is beautifully wooded, with many fine streams. Fruits ripen early. The apricots are past, and I have been eating peaches, figs, apples and melons, and even a few grapes. I have also seen orange trees, well laden with fruit.

25th December.—Through the Lord’s goodness I can again record that I have been holpen thus far, and I trust that you have also been assisted in your labours on this occasion. I have been much with you in spirit, and I have tried to rejoice with you in the remembrance of this blessed day. On Friday evening I had my first service, and then two preparation services on Saturday, which, with speaking to the parents of more than eighty children who have been baptized, fatigued me a good deal before Sabbath came. The congregation was very large, so that the place prepared for the services had to be doubled in size, and this, with the open air, require a great deal of exertion to make them hear. On Sabbath I was very hoarse, but got on very well, and was enabled to preach and to serve four tables without my voice failing. When I came home, though I did not feel fatigued, I was so worn out that when I lay down for a few minutes I slept full three hours most soundly, and was quite refreshed for the evening service.

Yesterday morning we had service very early, after which I sat full ten hours in the aanneming (confirmation) with some eighty young people, of whom forty-two were received, and were this morning voor-gesteld (presented). The attention from the commencement was much better than at either of the former church-places, and some of the people appear to have received deep, might it but be saving, impressions. The interest manifested in the hearing of the Word was great, and from the earnestness with which some spoke about it I would hope that the Lord has been with us. I have to thank and praise the Lord that He has so supported me, body and soul, but still there is much to complain of—a hard, unfeeling and unbelieving heart, even in the midst of earnest preaching, and much self-confidence and pride. The way in which the people here treat me tends but too much to elevate me, even though I be unconscious of it. The impressions which appear to have been produced have made the people still more anxious that I should come here, and some of them have been pleading with me for hours that I should accept a call.

On Saturday two men arrived here with an ox-waggon from Zoutpans-berg, bearing a letter from the Commandant Potgieter. They beg me to come thither, as the poverty of many of the people will not allow them to travel thus far, and since it would not be safe to leave the frontier towards Moselekatse, where they are altogether unprotected. The distance—fourteen schoften to the north-east from here—alone prevented me from going. Potgieter asked me to appoint a time when some other minister, or else myself, should come to them, and I have fixed September. When the men heard that they could not be visited for such a time, they were in tears, as they had hoped I might go with them, and when they left again they could not speak. I hardly know what to say when the people begin to discourse about their spiritual destitution, and their desire after the Word. They plead their application to the Ring (Presbytery) two years ago, and Papa's promise to help them, and urge the situation of Bloemfontein between Mr. Reid and Mr. van Velden as a reason why they should have a minister here on the uithoek (far corner). Suppose another minister, say John Neethling, should refuse to come here, but be willing to take Bloemfontein, what would you think of my coming here ? Perhaps you say, Foolish boy ! but the way in which some of the people here plead really moves my heart. Many are in a fit state for receiving the seed of the Word. May the Lord in His mercy help them.

Mooi River, 11th January, 1850.

My last letter I concluded on Christmas Day, and I shall simply commence this letter by resuming the narrative from that date. From C. Kruger’s we travelled in a south-easterly direction, and after crossing the Magaliesberg we reached Andries Pretorius’, where we stopped for the night. He treated me with great kindness and made great professions of sorrow over the decay of religion in the land. I rode a considerable distance with him on horseback the next day, when he asked me if he might not come to the Lord’s Table, as he had so longed for it at the last church-place. I spoke as faithfully as I could; and he said that it really was his most earnest desire to serve the Lord, but acknowledged that he was living in enmity with Biihrmann the Hollander, and I am glad to say that he stayed away from the Table. He desired to be remembered to you, as also did his brothers Piet and Bart, the former of whom is very well spoken of here. I had also a good deal of conversation with A. Pretorius on political matters, but into this subject I shall not now enter. This much I can say, that there does not exist the least fear for another outbreak [of the Boers against the British], though there is a small war-party who are doing all they can to disturb the peace. Unfortunately they are but too much encouraged in secret by some parties in the Sovereignty, and even in the Riet River, who profess to be loyal British subjects. But I see I must not begin with this, or I shall not know where to end.

From Andries Pretorius’ we rode a small schoft to the farm of D. Erasmus, where church was to be held. Here I had the usual work, and though the congregation was not as large as at the former church-place, the number of children brought for baptism was much greater (125), as the people of these parts had not been able to attend the services of Messrs. Faure and Robertson. I had a service on Friday evening, two on Saturday, and on the Sabbath I dispensed the Lord's Supper. It sometimes makes me unhappy to think that I must preach God’s Holy Word with so little preparation, and though circumstances prevent my studying much, yet I might live much more in a state of mind which would be a continual preparation. Oh ! could I but more live in heaven, breathing the spirit of God’s Word, the Lord would abundantly make up the want of regular study.

After the service I was very unwell, and was advised not to preach again in the evening, which advice I followed. On Monday I had only a very short service, for the confirmation of those who had been admitted as members on Saturday, and for the baptism of the children. I had caught a severe cold from the continual draughts to which I was exposed, especially when coming heated out of church, and the cold was accompanied with rather severe fever. Immediately after service I had to ride on horseback for several hours, the waggon having gone on early in the morning, since the distance we had to travel to the next church-place did not allow of our losing any time.

During the week we journeyed nearly due east to the district of Ohrigstad. The town and neighbourhood have been abandoned, though exceedingly fertile, on account of the disease which has carried off so many victims during the last two years, and all the people have trekked out to the Hoogeveld (plateau), where the climate is as salubrious as can be wished. For the greater part of the way we travelled through a thickly-wooded country, very sparsely peopled, though we were able to spend every night on a farm. The church-place and its neighbourhood along the Hoogeveld is quite bare, and much cooler than a great part of the low country through which we had travelled. We reached our destination on Friday afternoon. New Year’s Day was spent in the desert. On that day we travelled eleven-and-a-half hours in order to reach a habitation, or else we would have had to spend the night in the veld, which is still infested with lions. During the whole of New Year’s Day I thought much of our dear home, and I am sure the absent members of the family also formed the subject of your conversation. How many and how great are the mercies which the Lord has granted to us since the beginning of 1849.

Valsch River, 25th January, 1850.

When I reached the church-place I was still very unwell, but was strengthened to do my work. The congregation was not very large, as the intimations had unfortunately not reached all the people. I baptized seventy-five children, and was told that there was a still larger number left unbaptized in this district. When we left the place on the Tuesday, I had for my fellow-traveller the far-famed Hollander Buhrmann. He is a plain Amsterdammer, who came out here to be a schoolmaster, and who has been compelled, perhaps not very unwillingly, to take part in political affairs. He occupies no office, though every place in the Government has been offered to him. He does good, I believe, in trying to keep the people at peace, but is rather permanlig (stuck-up), as the people say. He is religious, but I fear has not true piety. By some he is much looked up to, and by others despised and hated. I had much conversation with him on all sorts of subjects, political not excepted, of which I may afterwards communicate the results to you.

During the journey back from Ohrigstad district I was still unwell, and very weak, but recovered gradually ; so that by the end of the week, when we reached Magaliesberg, I was nearly quite well, though still weak and very much fallen off in flesh. I had purposely not intimated any service for Sabbath the 13th, that I might have a day of rest; and I am thankful that I did so, as I was much refreshed for the hard work at Mooi River. Unfortunately I did not enjoy so much quiet as I had hoped for, as there were two or three other families come to the place, and my companions always strove to be with me. (I did not mention that Caspar Kruger and Frans Schutte accompanied me for the whole j ourney.) I trust, however, that the day did not pass without a blessing for myself. On Monday we left, and spent the night at Gert Kruger’s, of whom I have formed a high opinion. He gave me a letter for you, on the subject, I believe, of my coming here. He feels very strongly on the matter, and I must say again that, were I not bound to Bloemfontein, I know where I should go. On Thursday afternoon, after having seen the Oog (source of river) in the morning, we reached Mooi River.

Monday the 21st was the day appointed for the sitting of the Volks-raad, and this brought a large number of people to Mooi River. There were above 400 waggons; and a very large place, which had been prepared and which could contain about 1,000 people, was not sufficient for more than the half. I was really astonished, when I rose in church on Sabbath morning, to see the multitude that was assembled. I preached on Friday and twice on Saturday, not without a blessing, I trust, though I cannot say that my own soul was in a very lively frame. I sometimes doubt whether it really be the Lord's assistance by which I am enabled to preach, or whether it be merely natural powers which, when excited, lead me to preach earnestly, and apparently with deep impression on the hearers.

On Sabbath I dispensed the Sacrament, and had by far too many communicants, though I had tried to set forth as faithfully as possible what Psalm xxiv. 4 represents as the way to God. My own heart was somewhat enlarged in speaking on the name Emmanuel, but I found that very few of the people are in a state to appreciate such subjects. What they want is knorren (scolding), and if that but produced any good effect, I would willingly hnoy; but I sometimes feel sad at the thought that the blessed Gospel of God’s love should be degraded to be nothing else than a schoolmaster to drive and threaten.

On Monday I preached on 1 John iv. 7, and tried to speak as plainly as possible on all the contention and enmity which prevails amongst them, especially in reference to the Raad, where disputes sometimes run very high. The meeting of the Raad had been postponed till Tuesday because of the service. Many professed to be very thankful, and I really think that a good feeling was produced, and that many felt the necessity of striving after peace and unity. In the evening I had another opportunity of speaking strongly on the same subject in my farewell address from Philippians i. 27. I dare not say otherwise than that I was much assisted from on high, both in body and spirit. The congregations were very large, and as the place for service was partly open, I had to exert myself very greatly, and on Monday was very hoarse. Yet I was so strengthened as to be well heard, and I have not felt my chest pained or even wearied. At ten that night I began with the church meeting, which lasted past midnight till two o’clock. Among other things they again asked me to come amongst them, and though I decidedly said that I did not see the least opening to do so, they insisted; and I believe they intend sending me a beroepschrift (letter of call), and also petitioning the Synod on the subject. May the Lord Himself in His mercy supply the needs of this poor destitute people !

There is one point on which I still wish to ask your opinion. I never prayed for the authorities, and of course the people observed it, and Wolmarans spoke to me about it. I felt it to be a delicate matter, and wished much to know how the preceding Commission [i.e. Messrs. Faure and Robertson] would have acted. I do not know myself what to think of the proceedings of the Boers against the English: in many respects they appear to me to be justifiable; but on this I hope to speak with you afterwards. Even supposing that they have done wrong, they appear to me to be of " the powers that be,” as they are now tolerated by Government; and as well as Paul could pray for all authorities, and for the Romans too, might I pray that the authorities may be ruled by the fear of God, and the Raad be enabled by His wisdom to do all for God's glory and the good of the people. I hope to receive from you a full statement of your opinion as to whether I have done right or wrong in this matter. I felt that I might be led to do it for popularity’s sake, and I prayed the Lord to preserve me from the same.

On Tuesday morning, after only two hours’ sleep during the night, I left on horseback ; and I must confess I felt the parting from some whom I had learnt to know well, and to whom I had become much attached. I rode with Elder Wolmarans to Jan Kok’s to baptize a child two days old ; but before we got there we were thoroughly drenched. Though I had no shift of clothes (the waggon being behind), and was obliged to let my clothes dry on horseback, I have felt no bad consequences, through God’s goodness. Elder Wolmarans, Andries Pretorius and many others desired to be remembered to you.

You may imagine how very strange and varied my feelings were on crossing the Vaal River again. I had passed over it hardly knowing whither I went and what might happen, and when I looked back at the Lord’s leading over the way, all the strength and assistance I had enjoyed, the blessing of which I had been the unworthy channel to not a few, I trust, and the measure of comfort with which He had enabled me to do the work;—and when I then thought on the little progress I myself had made in grace, on the want of true love to my fellow-sinners, on the hardness and indifference of my wicked heart, on the absence of that true heavenly-mindedness in which an ambassador of Christ ought to live, on all the pride and self-sufficiency with which I had taken to myself the glory which belongs to God alone—surely I had reason to glory and rejoice in God, and to weep in the dust at my own wickedness. How fatherly have not the dealings of my Covenant God been with me, how unchildlike my behaviour towards Him. Oh ! bless the Lord with me, my dearest father, and praise Him for all His loving-kindness and long-suffering, praying that the Lord Himself would pardon and renew me, that I may be fitted truly to glorify Him.

Bloemfontein, 11th February, 1850.

At length I have again reached my dwelling-place (for home I cannot call it), and shall try and finish my narrative. From the Vaal River I rode to old Daniel Cronje’s on the Rhenoster River, where I had service that Tuesday evening and twice on Wednesday. The number of people was very small, as many of them had been attracted to the services at Mooi River by the sitting of the Volksraad. On Thursday I took my departure for Valsch River, and after having again experienced God’s goodness in finding the Rhenoster River just low enough to get through (though it had been excessively full the night previous), reached the church-place on Friday morning. There was a very good congregation assembled, and though I felt rather unwell, I was helped to perform the usual Communion services on Saturday, Sabbath and Monday. On Tuesday I left again for Winburg, which I reached on Thursday.

You cannot imagine the excitement of the people at Winburg about the appointment of Mr. van Velden to Harrismith, and I cannot say with what astonishment and indignation I was filled on receiving the intelligence.5 Such unprincipled robbery ! Such debasing of Christ’s servants to be the servants of political speculation. Here there are 3,000 souls, many hungering and thirsting; there not thirty. But enough. The matter gives me much work in writing to Cape Town whilst I am anything but well. But the Lord will provide.

The continued prosperity of our journey was interrupted at Valsch River by a solemn stroke of the Lord’s hand. Deacon P. Coetzer died there on Tuesday, 29th January, after having been my companion in all our journeyings. He had been ill about fourteen days, and complained of pain in all his members, especially his back. Some say it is the Delagoa disease, but this I cannot believe, as we kept far from the district where it has hitherto prevailed. He died trusting in the Lord, and I believe truly one of those who will be for ever with Him in glory.

The tremendous strain which arduous journeys such as that which has been described cast upon the youth of twenty-one could not but tell upon his strength. He informs the home circle that on his arrival at Bloemfontein he was still “weak, thin and very pale." The recovery which he made from the serious illness which had assailed him across the Vaal awakens frequent expressions of gratitude towards God. "Many people say that Deacon Coetzer died of the Delagoa disease, to which so many have succumbed in the back part of the country beyond the Vaal. As I was unwell at the same time, and exhibited the same symptoms with which his illness began, the report was spread that I was suffering from the same malady On my arrival at Winburg I found the people so alarmed that they almost persuaded me that I had the Delagoa disease. Though I could not see any danger myself, yet I could not help thinking of death, and through the Lord’s goodness the fear of death was taken from me.”

The Sovereignty, especially along its south-eastern border, remained politically in a condition of perpetual disquietude. About this time a farmer named van Hansen was cruelly murdered, together with his wife, four children and two servants, by a party of Bushmen, who appeared at his door and demanded to be supplied with tobacco. The murderers were retainers of Poshuli, brother of Moshesh,—a robber-chieftain whose depredations kept the farmers of the vicinity in a continual ferment of anxiety. The untoward conditions prevailing on the frontier are referred to in letters written during the month of April, 1850—

After I parted from John I had a very pleasant ride to Adam Swane-poel’s. The number of waggons [of the folk who had assembled for service] was about forty, but that number was very unexpectedly diminished. After the morning service on Sabbath a message was brought to one of the farmers from his father-in-law, bidding him to come home immediately, whether his child was baptized or not, as all the people in the Koesbergen were going to trek. The message confirmed a report that had previously been spread, that the Cafire chief Basouli (Poshuli) had fortified Vechtkop, and that the Cafires had sent away their cattle, and appeared to be secretly preparing for war. At the close of the afternoon service nearly the half of the people left, and the minds of the remainder were very much disturbed. From the conversation I had with Mr. Vowe6 on Monday, I fear that there is truth in the report, and it is suspected that Basouli is aided in secret by some more powerful chiefs (Letsea,2 some say, or Moshesh), as he is too weak to attempt anything alone. I shall let you know as soon as anything more decided happens. May the Lord in His great mercy restore peace in these times, that His Word may have free course and be glorified.

Our three magistrates at the last Circuit Court sentenced five Bushmen to death for the murder of van Hansen and family, and one for the murder of a Cafire. All the six are in prison here. Saturday’s post brought the Governor’s confirmation of the sentence, which is to be carried out to-morrow week. We have a catechist here from Thaba Nchu to instruct them. Still, I shall try and do something for them through him, in order to prepare them for that awful moment. At their execution I cannot be present, as I have to leave on Monday after the sermon for Burgersdorp, and have church appointed on the way thither at Hendrik Snyman’s.

In spite, however, of disquieting rumours and occasional interruptions, Murray applied himself with assiduity to his parochial tasks. The instruction of the young was one of his chief cares. The dearth of qualified teachers in South Africa, as well as the grievous lack of ministers, was the cause of loud lament at each meeting of synod or presbytery. Teachers had to be imported from abroad, and those who arrived at these shores received immediate appointments. Towards the end of 1849 two Hollanders named van der Meer and Groenendaal landed at Cape Town from a Dutch ship, and were assigned by the Governor to those distant and needy fields, Bloemfontein and Riet River. Van der Meer was accompanied by his wife, and Murray relates that on his return from one of his numerous visitation tours he found this worthy couple installed in his parsonage,—robbing him of his privacy, but relieving his solitude and adding sensibly to his comfort. His church building, in the meanwhile, was making steady progress, and tenders were invited for the construction of a school-house, which it was proposed to erect by public subscription.

Correspondence of every description engrossed the most of his spare time. The burden of four parishes, and the pressing needs of the emigrants beyond the Vaal, lay heavy upon him, and occasioned much anxious thought and a heavy official correspondence. To the members of his family, and especially to his father, he writes with regularity and occasionally at great length. He exchanges letters with friends at the Cape, with parishioners like Andries Pretorius and Gert Kruger on the further side of the Vaal, and with men of the evangelical circle in Holland, like Dr. Capadose. Nor, even in these early days, was there any lack of visitors at Bloemfontein, for though remote the town was central, and highways radiated from it to every part of South Africa. Missionaries passed through with considerable frequency, among others Robert Moffat, the famous pioneer of missions to the Bechuana, the Rev. J. J. Freeman, Secretary of the London Missionary Society, and the Helmore family, whose later history forms so tragic a page in the annals of South African Missions. Bishop Gray of Cape Town, to whom reference has already been made, was a visitor in the winter of 1850. Murray mentions this visit in a letter to his brother—

We had the Bishop here last Sabbath. He wished me to tell you that he will most likely come to Burgersdorp from Cradock. I rode out with him for a distance of one-and-a-half hours (nine miles) on horseback last Tuesday, and had a little chat. He is exceedingly active, and will not rest till he has churches everywhere. I tried to probe him on Puseyism, but he says there is no such thing in the Colony, only different shades of opinion. ”The jealousy of the Dissenters, and the ignorance of others, is the cause of all the outcry.” I told him that if he sent a man of evangelical sentiments [to Bloemfontein], I would be delighted to welcome him as a brother.

Though Murray’s health seems to have gradually improved during the winter of 1850, he had no relief from incessant travelling, sometimes by horse-waggon or Cape cart, sometimes (as in the territory beyond the Vaal) by ox-waggon, frequently on horseback, exposed to biting cold in winter or tropical downpours in summer, and always over ill-made and ill-kept roads. Occasionally he was overtaken by some “moving accident by flood or field.” Of one of these he tells in a letter to his father—

I had a great deal of rain on the way back [from Smithfield], and was twice detained by spruiten (river-courses) being full. On Thursday I experienced the Lord’s gracious preservation at Kaffir River. You know the drift (ford) is very ugly, and the horses, though good, were unaccustomed to the water. We unharnessed two horses, and made the boy ride on one, to lead the waggon through. In the middle of the stream the rope broke, and the boy was obliged to make for the bank. Our leaders took fright at the noise of the water dashing against the stones, and turned round twice in the stream, so that they nearly broke the pole. While the coachman was engaged in putting the front horses straight, the right wheeler, who could not stand against the strength of the stream, fell right over the pole, and both he and the left wheeler so kicked and struggled as to completely free themselves of' the harness. With all this confusion the waggon had been swept from the paved roadway, and as the horses were powerless to draw it up-stream, were obliged to make for the nearest point of the bank, and there to outspan. We then sent to Bekerfontein for spades, dug a road for ourselves, and then obtained some mules from a waggon standing on the banks of the river, and so were drawn out. Through the great goodness of God we thus got through with no other loss but that of time, though the hind-harness was a little broken. I suppose that we were nearly half-an-hour in the river, with the water sometimes washing against the buikplank (floor) of the waggon. Oh ! for a heart to recognize God's goodness aright, and to feel more and more bound to His gracious love and service.

In the course of July Murray paid a brief visit to Graaff-Reinet, and was greatly refreshed by his intercourse with the home circle. The residents of his birthplace seem to have made much of him, for he refers to the period of excitement through which he passed, and to the marks of esteem which were accorded him. His stay was short, as usual, and on the 18th July we find him back at Bloemfontein, and writing to his parents in the following terms—

To his Parents.

Through the goodness of our gracious Heavenly Father, I arrived here in safety yesterday (Wednesday) evening, and take up my pen at the first leisure moment to do myself the pleasure of corresponding with you. The doormalkaar (confused) state in which I found the house, and the business with which I have already been assailed in regard to the building of the church, and all the other duties still awaiting me, drive my thoughts to the dear home I left, and from which I shall now so long be absent. Though my journey possess nothing very interesting, yet I shall begin my narrative from Tuesday morning. That day we had a long and not very pleasant ride against the wind, and reached Hendrik Ekkert's a little after sundown. We found him not at home, though he had told me that he expected to be back on Tuesday from Richmond ; and we were obliged to content ourselves with bedding on the rustbank 8 and on some chairs in the voorhuis,9 of which the old Englishman fortunately had the key. On Wednesday we had a much more pleasant ride, though we could not reach Willem Venter's owing to one of the horses getting sick, and spent the night at Wild-fontein with the van der Walts. During the day I was able to collect my thoughts after the excitement I had been in, and enjoyed almost more in the retrospect of the hours spent among the dearly-beloved members of the family at Graafi-Reinet, than when there. I tried to feel the exceeding privilege of loving each other in Jesus, and the greatness of the blessing granted us in the assurance that not even death, much less any short distance on this earth, can separate us from the love of Christ. . . .

On Thursday we rode further, and after having left my riding horse dying at Willem Venter's, reached Colesberg after noon, but too late for the post. I found Mr. Reid and family well, and rode on that evening to old Christian van der Walt’s. From him I heard a good deal about the Colesberg troubles. He says his reasons for signing the petition for the removal of Mr. Reid is the old business of the Gezangen and the Herderlijke Brief.10 The latter appears to lie very heavy on him, especially the obnoxious expression of "doorboren het hart van Gods kin-deren.” At the Sacrament in Colesberg there was only half a table of men [at Communion], and a few more of women, principally Seacow River people.

On Friday we crossed by the pont, though the river was very empty, and reached old Hendrik Snyman’s about two, whence I started immediately with him and the Viljoens for Henning Joubert’s, which we reached about ten at night, having ridden twelve hours that day. We outspanned for an hour at Mr. Pellissier’s, who enquired very kindly about you and expressed a longing to see you. On Saturday I rode to Smithfield, which I reached about three o'clock, and on enquiry I found that no post was to leave that week. We had a pretty good congregation there, though there were not many people from beyond Caledon. I feared much that we would have very unfavourable weather, but in this matter God's goodness also cared for us, and though I had to preach in tents in the open air, there was neither wind, rain nor excessive cold to disturb us. In addition to my Dutch services I had also an English service, which I have been requested to hold regularly when I come. The Dutch people were attentive, sometimes interested and impressed. Oh 1 for more evident marks of the Spirit’s presence and power. . . . The time I spent at Smithfield was very pleasant, and I was made very comfortable in their tent by the Viljoens. The new churchwardens, with whom I am on the whole very well pleased, were voorgesield. I am glad to be able to say that a beginning has been made with church building. We received several tenders, and accepted one for £325. I think I mentioned that the dimensions were sixty-five feet long, seventeen wide and ten high in the clear. After the people knew that a commencement was to be made they subscribed very liberally.

On Tuesday I left Rietpoort, and yesterday evening I arrived here, finding the house as I left it. Mr. Stuart has gone to Bethany, but is still my guest. So are the van der Meers, though they propose to go to-morrow into Drury’s house, which they have bought for £100. It was a very great disappointment to hear that the Helmores spent a week here during my absence, so that I have a second time missed the pleasure of seeing them. I found a very kind letter from Dr. Capadose awaiting me, and felt ashamed at this new memento of the affectionate interest with which many had looked on us in Holland. And when I think of the tokens of esteem so lately conferred in Graaff-Reinet on such an unworthy subject, I really feel humbled. Oh ! for the time when our souls shall praise the Lord aright for His mercies.

I also had a letter from Rev. van Velden which has put me sadly about. He says it will be impossible for him to be at Winburg before 15th October, and thus it would be the middle of November before we could start for the North, where we would just be in the unhealthiest of the season. This is, however, not all; but the disturbed state of the country there (according to the reports of the travellers) makes me anxious to go as soon as possible, if the preaching of the Word might not move them to peace and quiet. I have here been advised to go as soon as possible, but have not been able to decide, and trust that my God will make the way plain before me. I am a little anxious now, as September is not far off, and arrangements will require soon to be made. I shall anxiously await Papa’s answer as to whether I should still wait, or would be warranted to go alone. . . .

A day or two later he writes again to his parents—

As to the matter which occupies so much of my thoughts, I received a letter from Mr. Faure on Saturday saying that the Governor has asked him to let me know that my journey must be postponed till I receive further intelligence. I shall write to-day to Mr. Faure to try and get leave, for it appears to me a most abominable application of the starvation principle, to deprive them of the Gospel for their political offences, and what is more, to lay a whole people thus under the ban for the sins of a few. I am sure that the great majority are living in quiet and peace, and anxiously longing for the promised visit. I pray to be made willing to wait, and to do the will of Him who can say, "I have set before thee an open door, and no man can shut it.”

Since writing the above I have received a letter from John’s neef (cousin)1 Buhrmann, requesting me in the name of the Volksraad to come over, and to make my arrangements so as to be at Mooi River at the time of the sitting of the Raad in October. May the Lord prepare a way for me and direct my steps.

His journey to the Vaal River emigrants was clearly costing him much anxious thought. The obstacles laid in his way were enough to have daunted a man who had laid the welfare of the Voortrekkers less deeply to heart. In addition to the adverse attitude of the Governor, and the unaccountable delay in the arrival of Rev. van Velden at Winburg, he was served at the last moment with a subpoena as witness in an important Court case. This threatened to throw his whole journeying programme out of gear. In those early years, when telegraph-lines had not yet penetrated to the Sovereignty, and mails were carried no further north then Bloemfontein, it was difficult to arrange itineraries, and arrangements once made must needs be scrupulously adhered to. Fortunately, the magistrate was amenable to reason, and authorized a private examination of Murray under oath, so that the latter was able to set out on his second visitation tour across the Vaal River on the 9th of October, having obtained ten weeks’ leave of absence for the purpose.

The story of this second tour we shall tell in his own words, derived partly from the account written for the Kerkbode, and partly from his more private letters to his parents.

After having conducted divine service at Valsch River, I arrived at Mooi River Town on Friday, the 16th October. There I was welcomed with the greatest joy by those who were present from various quarters for the session of the Raad, which had just that day come to a close.

I was soon convinced that this visit was well timed, for from all parts of the congregation the people streamed together, in numbers of certainly not less than 500, although many had been prevented from coming by the drought and the harvesting season. In the village itself I was pleasantly surprised at the sight of the walls of a roomy cruciform church, nearly ready to be roofed over. I could not but conclude that, in spite of much that is faulty, a truly great interest is here displayed in religious matters.

Though the church was still incomplete, we were able to make good use of it on this occasion, for canvas spread over the walls sheltered us from the sun. The only complaint was of lack of room, since the building was barely large enough to contain the whole audience. I noted great interest in all the services, though the excitement in connexion with the session of the Raad could not but have a detrimental influence ; for the feelings of many had been greatly disturbed. The preaching of the Word, nevertheless, was not unattended with blessing. More than one came to assure me how good he had found it, after having suffered want for so long, to experience satisfaction of soul in the Word of life. The usual services were held on Saturday, Sabbath and Monday. On the latter day seventy-four children were baptized and twenty-four young people confirmed and presented to the congregation.

At Mooi River the people immediately began again to speak to me about my coming hither, and I gave them the same answer, that were Bloemfontein but supplied, I would gladly come over. In the course of the journey' I have at times longed to labour here. Truly the harvest is great. I believe the churchwardens are going to send me a regular call, and also a petition to the Synodical Committee, signed by the people. This is not in the least my work, and I distinctly told them that I did not see the least possibility of leaving Bloemfontein, but advised them rather to call John Neethling.

On Tuesday morning we started for Suikerbosch Rand, and rode nine hours by ox-waggon north-eastward to the Gats Rand, where a small congregation was collected of those who could not come to the dorp. I preached that evening and next morning, and baptized eleven children. A woman was here brought to me to speak to, in distress about her salvation. I cannot imagine a more fearful case of a person under the power of Satan. She has already attempted some five or six times to take her own life. It appears that she was formerly very religious, but now she says she is lost,—and such perversity in condemning herself I never saw. When she hears of God’s grace or Christ’s mercy, it only increases her own misery ; for this, she says, will be her condemnation, that she refuses such mercy and her heart rejects such a God. When I came to her she begged of me with clasped hands not to speak to her, as she would have to answer for every word ; and when I offered to pray she burst into tears, saying that she would only mock God. Speaking to her one would think that she was in full possession of her reason, and she shows an intimate knowledge of the Bible. I really trembled at the power of Satan, and wondered at the goodness of God in not surrendering more of us, who abuse the day of grace, as she says she has done, to the terrors of His wrath.

Two days’ more travelling due east by ox-waggon brought us to the farm of Koos Smit, in the Suikerbosch Rand. This is a rather hilly district, healthy and fruitful, occupied by respectable and rather religious people, mostly from Beaufort and Zwarteberg (Prince Albert), among whom old David Jacobs has been the means of keeping alive a certain degree of religion. The congregation amounted to upwards of 200, and gave no reason to complain of inattention, though I felt humbled at the absence of the power of the Spirit with the Word. . . . We had services on Thursday and Friday night, on Saturday and Sabbath. Out of eleven candidates only two were received into membership, and thirty-eight children were baptized.

As the distance to Lydenburg was great we were obliged to travel on horseback through a bare and uninhabited country. The waggon was sent forward on Saturday in order to afford us lodging, and on Monday morning we started early and rode for about nine hours in a northeasterly direction. On Tuesday we went some ten hours further, over high flats with good water and grass, but without wood, and therefore not yet inhabited. On Tuesday night we reached the farm of Andries Spies, where church had been appointed for a few people in the neighbourhood, who were too far off to reach the other church-places. There was a small congregation of some fifty persons, to whom I preached thrice on the Wednesday, administering baptism also to eleven children. Thence we started early on Thursday morning, and after travelling fourteen hours we reached Lydenburg on Friday morning at about ten o'clock. About eight hours on this side of Lydenburg the appearance of the country suddenly changes, and I was quite taken by surprise on suddenly finding myself in the midst of high rugged mountains, and travelling on roads with which the Sneeuwberg roads can hardly be compared. It is a beautiful grass country with large streams of water, and is well supplied with the suikerbosch (protea). Lydenburg lies in a valley between two of these large mountain-ranges, the slopes of the Drakensberg, and is about four hours distant from the unhealthy country. Ohrigstad is about six hours to the north-east of Lydenburg, but is deserted. Though so near each other the climate of each is different. Places sometimes adjoin each other of which the one (the lower) is unhealthy, and the other quite safe. Lydenburg has only two families living there as yet, though Ohrigstad had some twenty large houses built, and a still larger number of residents.

I was hardly off-saddled before I had to begin my work, as we had to leave again early on Monday morning. Both on Friday and on Saturday I had to sit late with the work that had to be got through. The congregation was large and the people were very attentive, and I was enabled to preach in earnest, so that by Sabbath afternoon I was perfectly exhausted. I had seventy-nine applicants for membership, of whom forty-nine were received, and 109 children were baptized. I was here as elsewhere pressed on all sides, and even with tears, to come to this side of the River, and if not, at all events to pay them another visit. On my saying that I trusted they would soon have a visit from some other minister, an old friend of Papa’s, Andries Beetge, answered, “But is not a year too long a time for us to suffer hunger?” and I could give no answer in return.

On Monday morning a little after sunrise we were again in the saddle, as church had been appointed for some people, who could not come to Lydenburg, on the Tuesday morning at a place some ten hours distant. We would have been there in good time, had we not been detained by rain in the afternoon. Here, however, as elsewhere, we found such kind people that we were made quite comfortable, and next morning we proceeded the remaining two hours to the appointed farm, where a small congregation was waiting. To them I spoke a word of exhortation, at the close of which they expressed the intensest desire for a more frequent ministration of the means of grace. After service we rode five hours further, always due east, along the same road which I travelled last year when so unwell; and I could not but feel grateful for the strength granted on the present journey.

Next day we had ridden only a couple of hours when we were detained as the orders for conveyance had not reached the place, and I enjoyed a day of rest; but I only felt my fatigue and weariness so much that I was incapable of doing anything. As the time was too short for us to travel by the high-road, we were obliged to take a short-cut through uninhabited boschveld (bush country), where we slept in a waggon on Thursday night, and thence reached the Bath at the Waterberg on Friday mid day. In the course of our ride we saw the white and the black rhinoceros, camelopards (giraffes), and an elephant, besides a multitude of smaller game.

Schoonspruit, 2jth November, 1850.

My first sheet I wrote mostly at the Bath, and have since then been prevented by continual occupation from again writing. On our arrival at the Bath we found only some twelve waggons, standing in lager, on account of the Caffres, and heard that the people of the neighbourhood were all gone to another lager near Magaliesberg. Church had been appointed here for the Zoutpansberg (Potgieter) people, and I was glad on Saturday evening to see thirteen waggons, well-loaded, arrive from there—a distance of nine schoften. I had a letter from Potgieter, lamenting that I had not fulfilled the promise I had half made to go thither, and begging soon to have the privilege of the ordinances there, as more than half of the people had been prevented from coming. And need of it there certainly is, as was proved by the applicants for membership, for of twenty-five only two were received. I did not administer the sacraments here, but was enabled to set forth Christ for the free acceptance of a simple faith with almost more plainness and earnestness than elsewhere. ... I did not, however, feel that certain reliance on God which I wished. I saw clearly that faith is a fight, and at moments I laid hold of the Lord, but alas ! I am so little accustomed to crucify the flesh and really to believe, that I found it hard work, which will require much more strenuous effort, much more wrestling with God in private, than I have hitherto given. Oh ! may the Lord give me true faith. I feel now that this is a sad life of mine, and that it requires a person of much more spirituality and habitual intercourse with heaven than I have, to travel in this way, as there is so very seldom the regular opportunity for private devotion ; and there is really nothing that can be a substitute for intercourse with God. I preached on Saturday and Sabbath, and intended leaving on Monday, but we were detained by rain. I could not then resist the entreaties of people who had come so far to hold additional services on the Monday. Baptism was administered to thirty-six children. May the Lord but add His blessing.

Before leaving the Bath I may mention that it derives its name from a beautiful warm bath, which is highly prized for its medicinal virtues in cases of fever, wounds and weakness. The stream is much larger than that of Bufiels Vlei (Aliwal North), and hotter, but without the taste of gunpowder. On Tuesday morning we left the Bath early, and after riding four hours came to Pienaars River, which we found overflowing its banks, so as to be perfectly impassable. We rode some four hours up along the stream, and fortunately found the water run down, so that we could cross. In the evening we reached the lager, after having been eleven hours in the saddle. We heard that the Boers had had a fight with the Caffres, but from all I have been able to learn by the minutest enquiries from all parties, the blame does not appear to be on the side of the Boers.

At the lager they asked me to baptize their children as they would not be able to come to the church. I refused, as I thought the most might manage to come, and the lager was to break up next day. I felt too that they were wholly unprepared for the administration of such an holy ordinance, drinking and cursing having been but too much the order of the day. The lager people, I should say, were mostly from the Hakie-doorns, where none but the wild sort live. I do not know whether I did right, but it is to me a very difficult matter to administer the ordinance to those who are without any preparation, though it is also hard to refuse it. And this appears to me to be one great argument for the first available minister being sent hither, as the ordinance is so often profaned unknowingly, while the people of the Colony all have a better opportunity of being instructed in the matter.

On Wednesday we had again a ride of ten hours, which brought us to the house of Frans Schutte, on this side of the Magaliesberg. He had been my companion the whole way from Mooi River. We went to his farm in order to have a day of rest, though such a short rest made me feel my fatigue all the more, and I was unable to derive that profit which I had expected from a day of quiet. I was even too listless to take up a pen and write to my beloved parents. On Friday we rode a couple of hours to the new church-place and site of a village on the north side of the mountain. The position of the town is pretty, with the mountain behind and a large view in front. The woods are still rather dense on some sides, and there is no lack of water. Some seven or eight houses have been commenced, and the church building is considerably advanced—all in the hope of soon having a minister. It is a large building eighty-five feet by thirty, and the walls are to be sixteen feet high. The congregation was so large that the church could not contain all the people, and I had to exert myself so much to make all hear, that I was quite knocked up when I came to rest on Tuesday.

You know what I think of the Magaliesberg people. My favourable opinion was confirmed as regards many of them. Contrary to my own expectation I was greatly helped to preach with some measure of feeling, and though I know not whether impressions on the unconverted will be abiding, I do trust that the Lord will gather some there. Before leaving I had the satisfaction of seeing that some whom I believe to be truly God’s children had been edified and quickened by the ministration of His most unworthy servant. I felt greatly humbled when one man who had formerly spoken very despondingly said at parting, “I hope afterwards to have an opportunity of telling you what great things God has done for my soul.”

At Magaliesberg I had the usual services on Saturday, Sabbath and Monday : 109 children were baptized (one child of thirteen I was obliged to refuse), and of seventy-seven applicants for membership thirty were received. In the spare moments the people were continually recurring to the one topic in which they are so interested, the obtaining of a minister, and Frans Pretorius wished me to tell Papa that he is ready, if I come, to fulfil his promise, to leave his farm and to come and live in the village, in order to take care of me. The matter causes me much thought, and I hardly know how to come to a decision when I get the call. My own inclination would soon decide the matter, though I really cannot assign a reason for the liking I have taken. But still I would tremble at the thought of taking a single step without a clear conviction that it is the will of the Lord. Though I do not yet see in what way, I feel assured that God will not forsake the work of His own hands amongst this people. A faithful God must satisfy that desire for the Word which He Himself has excited.

The churchwardens pressed me to come again in April for a‘couple of Sabbaths, in order to open the churches at Mooi River and at Magalies-berg. When I promised to do my utmost to get Mr. van Velden or John to come at that time, they said that all the people wished myself to come. I do not write this from vanity, but to ask Papa for an opinion. The churchwardens continually urged as a strong reason for my going thither, the extraordinary unanimity of the people in calling for me, and I must confess that I was myself sometimes staggered by the urgency with which they invited me. This was especially the case in the Morikwa, whither I went for the first time, and where many on parting came to me with tears, to beg me to come again rather than send another. It occurred to me that it might be a token of God’s will in the matter, that the whole people, otherwise so divided, should unite so firmly in fixing their choice upon me, and will take no refusal. . . .